REBELLION: 1775-1776

2. Loyalists II: Traitor!

- Anti-Loyalist broadsides and blank forms of allegiance, 1775-1776 PDF

- Anti-Loyalist violence, 1774-1775: incidents compiled by Peter Oliver, Origin and Progress of the American Revolution, 1781 PDF

- "My Kinsman, Major Molineux," short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1830, depicting anti-Loyalist violence in pre-revolutionary Boston PDF

David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, 1789

From the beginning of the revolutionary period in the 1760s, British supporters were harassed, intimidated, and often attacked by Patriot mobs. As war approached in the 1770s, the victims of Patriot wrath expanded to include lukewarm supporters and the vocally undecided, and the attacks upon them and the damage to their property, escalated in severity. "Humanity would shudder," writes Patriot historian David Ramsay, "at a particular recital of the calamities which the Whigs inflicted on the Tories, and the Tories on the Whigs" (i.e., the Patriots on the Loyalists, and vice versa). Here we will view the actions, nonviolent and violent, used by Patriots at the outbreak of war to control and avenge Loyalists.

Anti-Loyalist broadsides and blank forms of allegiance, 1775-1776. With the surge in war preparedness after the Battle of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, actions to curb Loyalist opposition also surged—and publicizing those actions became strategically important. In New England the Patriot Committees of Safety published broadsides including "Wanted" posters (not titled as such at the time) and the coerced recantation statements of intimidated Loyalists. What would be the effect of viewing these statements in newspapers and publicly posted broadsides? In addition are two blank forms to affirm allegiance to the U.S.: one to be signed by Loyalists renouncing allegiance to Britain and the other to be signed by anyone assuming an office in the new government. How do the two forms differ? (3 pp.)

Anti-Loyalist violence, 1774-1775: incidents compiled by Peter Oliver, Origin and Progress of the American Revolution, 1781. One Loyalist victim was the Boston judge Peter Oliver, who was forced from his judgeship and driven out of America to Nova Scotia and then Britain. "I took my leave of that once happy country," he wrote in his diary in 1776, "where peace and plenty reigned uncontrolled until that infernal Hydra Rebellion, with its Hundred Heads, had devoured its happiness . . ."1 In 1781 he wrote an angry history of the prewar period entitled Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion, in which he adapted a newspaper list of violent acts upon Loyalists over a six-month period. What kinds of intimidation and injury were inflicted upon Loyalists? What did the attackers hope to accomplish? Explain Oliver's tone in the first and last sentences of the piece. (5 pp.)

"My Kinsman, Major Molineux," short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1830, depicting anti-Loyalist violence in pre-revolutionary Boston. Nathaniel Hawthorne's story of 1830 is set in colonial Boston of one hundred years earlier when, in Hawthorne's words, "colonial affairs . . . had caused much temporary inflammation of the popular mind." Bostonians resented the new taxes imposed in 1730 by Britain to replenish its depleted treasury, aggravating their anger over Britain's removal of their right to elect their own governors in the late 1600s. In this atmosphere, the story depicts mob vengeance inflicted on an aristocratic American-born British official as witnessed by the official's eighteen-year-old nephew, a country boy setting out to create his adult life (perhaps representing the fledgling nation-to-be). The official, Major Molineux, has been tarred and feathered by the mob, an act of humiliation and retribution long employed in colonial America by irate crowds upon unpopular persons—especially Loyalists during the revolutionary period. The mob would strip the victim to the waist, pour hot tar over his/her body, and roll the person in feathers that would adhere to the tar. Usually the person was paraded about the area in a cart before being released, perhaps, or threatened with further violence. Occasionally the victims would die. In another story, "The Hutchinson Mob," published in 1840, Hawthorne described the mob attack on the house of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson in Boston during the Stamp Act controversy of 1765; excerpts of this story are included in a sidebar. How does Hawthorne depict the Bostonians who tar-and-feather Major Molineux? How does the naive nephew respond? What is Hawthorne illustrating about mob behavior and bystanders? (12 pp.)

Note: Many Loyalist writings are included in Themes I-IV. See the chronological all-texts list.

Discussion Questions

- From these readings, describe the methods and motivations of anti-Loyalist (and anti-British) actions.

- Compare the nonviolent actions of the Patriot Committees of Safety and the violent actions of Patriot mobs.

- For both violent and nonviolent actions, how did they serve as vengeance? as instruments of control? as self-validation for the Patriots?

- How do leadership and group solidarity function in (1) the quasiofficial committee of safety and (2) the transient violent crowd?

- What would be the effect of viewing the publicly posted anti-Loyalist broadsides and reading the recantation statements in newspapers? What gives them their power? What function did they serve in a transitional period to war?

- How do the two allegiance forms differ in purpose and wording? Why would blank forms be printed in advance?

- From the six-month list of mob attacks presented in Oliver's Origin & Progress of the American Rebellion, characterize the motives and methods of the attackers.

- What commentary and tone does Peter Oliver add to the newspaper list of anti-Loyalist violence?

- Why does he call the mob attacks "very innocent Frolics of Rebellion"?

- What is Oliver's point in his last sentence? Of what is he accusing the revolutionary leaders?

- Briefly summarize Nathaniel Hawthorne's short story "My Kinsman, Major Molineux." Why is the protagonist of the story a young country-boy nephew of Molineux, and not Molineux himself, or one of the attackers or other bystanders?

- How does the opening paragraph of the story presage Major Molineux's fate?

- How does Hawthorne reveal to the reader, but not to Robin, that secret conspiratorial activities are afoot in the town?

- How does Hawthorne depict the Bostonians who tar-and-feather Major Molineux? Why is Molineux, although a native Bostonian, the victim of anti-British violence?

- How does Robin, his naive nephew hoping to begin his independent life, respond to seeing his humiliated uncle? What is Hawthorne illustrating about mob behavior and bystanders?

- To what extent does Robin represent the fledgling United States? (Don't equate the two; Hawthorne is more subtle than that.)

- To what extent does the story—written in 1830, set in 1730, and depicting prerevolutionary violence of the 1770s—represent similarities among the three periods in American history?

- How do you judge the incidents of mob action in these readings—historically, politically, and ethically?

- From your knowledge of these revolutionary leaders, how would they judge anti-Loyalist violence? Compose a dialogue among three characters: a Loyalist, a nonviolent Patriot leader (see lists below), and a fictionalized leader of Patriot mob action.

Patriots: John Adams, Samuel Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, John Dickinson, William Henry Drayton (Loyalist-turned-Patriot) Loyalists: Peter Oliver, William Franklin, Joseph Brant (Thayendenegea), Joseph Galloway, Myles Cooper, Charles Inglis

Framing Questions

- What rebellions and "civil wars" occurred within the colonies as war approached in the mid 1770s?

- How did colonists express and debate their differing opinions?

- How did they deal with political opponents?

- What caused the moderate voice to fade from the political arena?

- What led Americans to support or oppose the ultimate goal of independence?

Printing

Anti-Loyalists broadsidesAnti-Loyalist mob violence

"My Kinsman, Major Molineux"

TOTAL

3 pp.

5 pp.

12 pp.

20 pp.

Supplemental Sites

Peter Oliver, Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion, 1781, full text (Internet Archive)

William Molineux, Forgotten Revolutionary (Boston 1775, J. L. Bell)

The American Revolution, overviews and primary sources (American Memory, Library of Congress)

- – Tories Spread Falsehoods in Canada

- – Continental Congress Resolutions Concerning Loyalists

- – Loyalists in Delaware and Maryland

- – A Loyalist Tract, 1781[?]

Teaching the Revolution, valuable overview essay by Prof. Carol Berkin, Baruch College (CUNY)

General Online Resources

1Journal of Peter Oliver, in Peter Orlando Hutchinson, ed., The Diary and Letters of His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson, 1883, vol. II, p. 48.

Images:

– To the People of America. Stop him! Stop him!, broadside, New London, Connecticut, 1775. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Portfolio 3, Folder 31a. Digital image accessed through Early American Imprints Doc. 14509, American Antiquarian Society with Readex/NewsBank.

– Portrait of Peter Oliver by unidentified artist, oil on paper, ca. 1780s. Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift of Mrs. Robert deW. Sampson to the Medical School, 1961, H583. Reproduced by permission.

– The Bostonians Paying the Excise-Man or Tarring & Feathering, British print, publ: Sayer & Bennett, 1774; copyright holder, if any, unidentified.

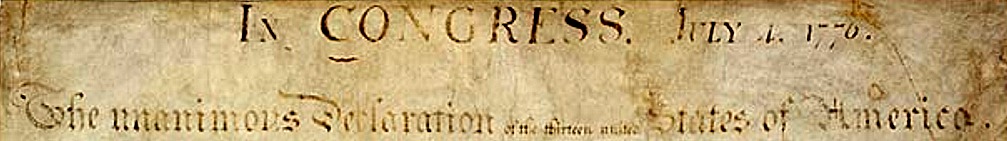

Banner image: Original Declaration of Independence, parchment, 1776 (detail); on exhibit in the Rotunda of the National Archives, Washington, DC. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

*PDF file - You will need software on your computer that allows you to read and print Portable Document Format (PDF) files, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you do not have this software, you may download it FREE from Adobe's Web site.