CONSTITUTION: 1787-1791

5. Adding a Bill of Rights

- On adding a bill of rights to the Constitution: commentary from letters, addresses, and newspapers, 1787-1789 PDF

- The Bill of Rights, 1789 National Archives – print version

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (France), 1789 Avalon Project

Jack Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the

Making of the Constitution, 19961

For many Americans after the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the decision to support or oppose the new plan of government came down to one issue—whether their liberties were jeopardized by its lack of a bill of rights. After all, they had rebelled against Britain because it had in their view ceased to respect their age-old liberties as Englishmen—liberties enshrined in the 1215 Magna Carta and the 1689 English Declaration of Rights. Having fought a long war to protect these rights, were they then to sacrifice them to their own government? Others countered that a bill of rights actually endangered their liberties—that listing the rights a government could not violate implied that unlisted rights could be restricted or abolished. And just what posed the gravest threat to individual liberties—the federal government or, paradoxically, the people themselves? A lot to consider in the intense debate over ratifying the proposed Constitution.

On adding a bill of rights to the Constitution: commentary from letters, addresses, and newspapers, 1787-1789. Did the Constitution need a bill of rights? In general, Federalists said no and Anti-Federalists said yes. If so, should it be added before or after the Constitution was ratified? Adding it before ratification meant a second constitutional convention, a calamitous prospect to most Federalists. Thus when five states proposed amendments at their ratifying conventions, they did so with the clear message that their vote to ratify committed the first Congress to submit a bill of rights. Which it did, with James Madison's leadership, on September 25, 1789. With Virginia's ratification over two years later, the first ten amendments were added to the U.S. Constitution—the first eight deemed the "Bill of Rights." (Two of the twelve proposed amendments were not ratified). Follow the discussion on the need for a bill of rights in these selections from newspapers, addresses, and correspondence, from late December 1787 to the summer of 1789, when Madison was leading Congress in its creation of the Bill of Rights. (8 pp.)

The Bill of Rights, 1789. As implicitly promised by the Federalists during the long ratification process, the first Congress under the new Constitution took up the challenge of constructing a bill of rights, and in September 1789 it proposed twelve amendments to the states for their approval. By late 1791, all the states had ratified the eight amendments that protected individual liberties, and the two amendments that reserved to the people and the states all powers not relegated to the federal government. (The two that dealt with congressional apportionment and salaries were not ratified.)2

Like the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights is a document to be read occasionally, with attention to content and meaning unnoticed before, or to particular relevance to issues of the day. We think we know it, but a re-read is always enlightening, even intriguing. Why is the Fourth Amendment so specific? Why is the Eighth Amendment so vague? Does "no law" in the First Amendment mean "no law"? Why is it "life, liberty, and property" in the Bill of Rights while it's "life, liberty, and happiness" in the Declaration of Independence? Where's the habeas corpus protection? the guarantee of "equal protection of the laws"? the right to a lawyer? the presumption of innocence in a trial? the right to vote regardless of gender or race? the ban on an official national religion? the ban on requiring people in public office to belong to a specific religion?3 Just 1,436 words; you have time. (2 pp., National Archives. Also see the excellent annotated hyperlinked Bill of Rights from Cornell University Law School.)

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (France), 1789. Drafted by the Marquis de Lafayette, who had ably trained and led American soldiers during the Revolutionary War, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was adopted by the French National Assembly in August 1789, one month before the U.S. Congress submitted the Bill of Rights to the states. While the documents are coupled forever in history for their timing and ideals, they diverge widely in context and outcome. The U.S. Bill of Rights concluded a three-decade struggle for independence and self-government, and it was deeply rooted in the English heritage of formalizing individual rights within government. In contrast, France adopted the Declaration of Rights at the very beginning of its ill-fated revolution—just six weeks after the storming of the Bastille in Paris in July 1789—with no historic scaffolding, no tradition of monarchs gradually relinquishing power. While France did not establish a permanent representative democracy until 1870, both nations revere their 1789 rights declarations as founding documents of their republics. (See also the French commentary on the American Revolution in Theme IV: INDEPENDENCE, #7, A Model for Europe.) (2 pp.)

Discussion Questions

- Overall, what impression did you get from the commentary in 1787-89 on the need for a bill of rights in the Constitution?

- What were the major arguments for and against adding a bill of rights?

- Why did support for adding a bill of rights reflect the Anti-Federalist position in the ratification debates?

- Why did the conviction that a bill of rights was not necessary reflect the Federalist position?

- Why did James Madison, a Federalist who opposed adding a bill of rights, lead the congressional process to submit a bill of rights to the states?

- Historian Jack Rakove writes that Americans' ideas of what their rights were did not change substantially after the Revolution, but what did change were "their ideas of where the dangers to rights lay and of how rights were to be protected."4 How does the commentary on the Bill of Rights in 1787-88 reflect this change?

- For American colonists, where did the dangers to individual rights lay before 1776? How were rights to be protected?

- By 1789, what events and issues had modified Americans' views of the threats to, and protections of, their rights?

- What amendments proposed by the states in their ratifying conventions were incorporated into the Bill of Rights? Which were added later as amendments? (See Supplemental Sites.)

- Identify a state-proposed amendment that has not been added to the U.S. Constitution. Argue that it should, or should not, be added to the Constitution. Conduct research to learn whether it has been introduced in Congress as a proposed amendment.

- Identify the rights that are protected in the original Constitution (Articles 1-7) and those defined in the Bill of Rights. In your judgment, which are the five most significant protections? Why?

- Compare the 1789 Bill of Rights with the following (see Supplemental Sites):

- – the amendments proposed by the state ratifying conventions, 1787-88

- – the earlier English rights documents (1215 Magna Carta, 1628 Petition of Right, 1689 Declaration of Rights)

- – the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, 1789

- – the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, United Nations, 1948

- What rights are defined in most or all of the documents? What do they share?

- How do the 1789 English and French documents differ from the 1948 United Nations document? Why? What values are apparent in all three documents (stated and unstated)?

- Study the French Declaration of Rights to identify the influence of the American freedom documents—the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. (Although the Bill of Rights followed the French Declaration by one month, the American discussion of rights in the 1780s gained wide attention in France.)

- More specifically, analyze the seventeen articles of the French Declaration for their counterparts (or lack of) in the American founding documents. What do the similarities reveal about the progress of liberty and Enlightenment ideals in the late eighteenth century?

- Consider Article 16 of the French Declaration: Any society in which no provision is made for guaranteeing rights or for the separation of powers has no Constitution. How was this concept part of the American ratification debate? Why did it merit its own article in the French Declaration?

Framing Questions

- How did Americans' concept of self-governance change from 1776 to 1789? Why?

- How did their emerging national identity affect this process?

- What divisions of political ideology coalesced in this process?

- How did the process lead to the final Constitution and Bill of Rights?

- How do the Constitution and the Bill of Rights reflect the ideals of the American Revolution?

Printing

Commentary on the Bill of Rights, 1787-1789The Bill of Rights, 1789

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, 1789

TOTAL

8 pp.

2 pp.

2 pp.

12 pp.

Supplemental Sites

Creating the Bill of Rights (Library of Congress)

James Madison proposes the Bill of Rights (James Madison University)

Amendments proposed by states' ratifying conventions (The Founders' Constitution, University of Chicago Press, and The Avalon Project, Yale Law Library)

- – Massachusetts, Feb. 1788

- – New Hampshire, June 1788

- – Virginia, June 1788

- – New York, July 1788

- – North Carolina, August 1788

National Archives, Washington, DC

- – Charters of Freedom

- – The Bill of Rights, proposed by Congress, Sept. 1789

- – Virginia Declaration of Rights, by George Mason, 1776

- – Q&A on the Constitution and the Bill of Rights

- – Magna Carta, 1215

- – English Declaration of Rights, 1689

- – Resolution of Congress Submitting Twelve Amendments to the Constitution, adopted 25 September 1789; dated 4 March 1789 (first day of first session of Congress).

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, 1789

- – French text (Assemblée Nationale de France)

- – English text, PDF (Conseil Constitutionelle, France)

- – English text, (Avalon Project, Yale Law School)

"Was the American Revolution Inevitable?," not-to-miss teachable essay by Prof. Francis D. Cogliano, University of Edinburgh (BBC)

Teaching the Revolution, valuable overview essay by Prof. Carol Berkin, Baruch College (CUNY)

General Online Resources

1Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Knopf, 1996), p. 289.

2The proposed amendment on congressional pay raises (that a raise must take effect after the session in which it was passed) was ratified in 1992 as the 27th Amendment.

3Habeas corpus: Article I, Section 9, clause 2 of the Constitution.

Equal protection of the laws: 14th Amendment, ratified 1868.

Right to a lawyer in a criminal trial: 6th Amendment of the Bill of Rights ("assistance of counsel"; extended to state courts in 20th-century Supreme Court decisions).

Presumption of innocence: not stated specifically in the American founding documents, but assumed in Amendments 4, 5, and 14, and affirmed in Coffin v. U.S. (1895). In the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789), it is stated in Article 9.

Right to vote regardless of gender: 19th Amendment, ratified 1920, for women.

Right to vote regardless of "race": 15th Amendment, ratified 1870, for black male citizens.

Right to vote regardless of "race": Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, for Native American male citizens (some states barred suffrage until 1948).

Ban on an official national religion: First Amendment of the Bill of Rights, establishment clause.

Ban on religious "tests" for public office: Article VI, paragraph 3, of the Constitution.

4Rakove, p. 289.

Images:

– Resolution of Congress submitting twelve constitutional amendments to the states, 25 September 1789 (details). Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives.

– Déclaration des droits de l'Homme et du citoyen, 1789 (Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen), painting: 1791 (detail). Musée Carnavalet, Paris, France; permission request submitted.

– Draft of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, by the Marquis de Lafayette, 6 July 1789 (detail). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, The Thomas Jefferson Papers (General Correspondence. 1651-1827, p. 586).

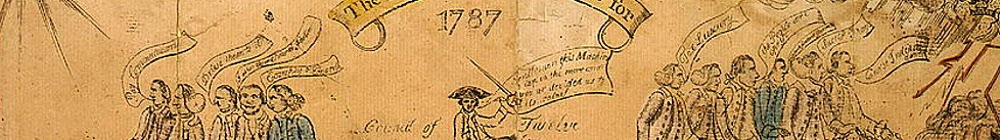

Banner image: Amos Doolittle, The Looking Glass for 1787, engraving, cartoon on the Connecticut ratification debates, 1787 (detail). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC4-1722.

*PDF file - You will need software on your computer that allows you to read and print Portable Document Format (PDF) files, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you do not have this software, you may download it FREE from Adobe's Web site.