CONSTITUTION: 1787-1791

1. Abandoning the Articles

- Founders on the defects of the Articles of Confederation, correspondence selections, 1780-1787 PDF

- James Madison, "Vices of the Political System of the United States," memorandum, 1787 PDF

Edmund S. Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763-89, 1956/19921

The "job" of Congress under the Articles of Confederation was to win the Revolutionary War, but the Commander in Chief himself knew that the nation's victory was achieved despite Congress. Not that it lacked conviction and ability among its members—what it lacked was power. Thrown together as a wartime government, the Articles created only a "firm league of friendship" among the states that jealously guarded their power and gave Congress short tether. After all, in 1776 the states had no intention of creating their own despotic Parliament. The Articles assigned Congress duties without risking tyranny, but it soon became apparent that this translated as the age-old bind: responsibility without authority. Win the war—but you can't tax the states to pay for it. Deal with European nations and the Indians—but you can't ratify treaties. Maximize commerce and trade—but you can't interfere with states' trade with each other and with nations. With Washington's leadership and the unifying goal of victory, the "united states" had won their war, but without this motivational glue the "league of friendship" proved insufficient to sustain and develop the new nation.

A collapsing postwar economy brought the lesson home—rampant inflation, plummeting farm and business income, bankruptcies and farm foreclosures, reduced export trade, no national system of coining or printing money, and a staggering war debt that Congress could not make the states pay. If the new nation did not honor its war debts to European lenders, its standing among nations would be nil. No way to start a country. More threatening was the internal danger of revolt as debt-strapped legislatures levied taxes on debt-strapped merchants and farmers facing impoverishment, a situation set to explode. Farmers' revolts in New England, especially Shays's Rebellion in western Massachusetts, raised the long-feared spectre of anarchy and mob rule, but Congress could do nothing, unable to compel the states to send militia units to quell the uprisings. The crises escalated—frontier Indian raids, state rivalries over river commerce, a bitter tug-of-war over control of the western territories—and a Congress powerless to act. The thirteen "united states" were not yet the "United States."

Founders on the defects of the Articles of Confederation, correspondence selections, 1780-1787. The Articles were "neither fit for war nor peace," wrote Alexander Hamilton, for they hobbled the fragile new nation that was struggling to defeat Britain despite its flimsy internal cohesion. What was wrong? What could fix it? Presented here are the thoughts of eight revered Patriots—George Washington, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Morris, Henry Lee, and Henry Knox—from their correspondence in the last years of the war to the eve of the Constitutional Convention. How were their observations and recommendations reflected in the 1787 Constitution that replaced the unmourned Articles of Confederation? How would Anti-Federalists have answered the concerns of these eight men, all Federalists who supported the new Constitution? (8 pp.)

James Madison, "Vices of the Political System of the United States," memorandum, 1787. Finally in 1786 the states agreed to meet as a whole and correct the "defects in the present Confederation." It was time to start over—and a road map was provided by James Madison, a member of the Virginia legislature, a former delegate to the Continental Congress, and a political theorist extraordinaire. As historian Jack Rakove aptly states, thirty-six-year-old Madison "was not so much a member of the generation that made the Revolution as he was of the generation that the Revolution made."2 On the eve of the Constitutional Convention, Madison composed a memorandum for George Washington, head of the Virginia delegation, listing twelve principal "vices" of the Articles. The first eight itemized the generally accepted weaknesses of the national government (i.e., Congress), and the last four specified defects of the states' laws—their multiplicity, mutability, injustice, and impotence. "The drafting of this memorandum," writes Rakove, "was essential to Madison's self-assigned task of formulating a working agenda that would allow the coming convention to hit the ground running."3 And that it did. Madison's "working agenda" spawned the Virginia Plan of Government that, with its emphasis on a strong national government in a federal system of checks and balances, provided the foundation of the U.S. Constitution. A challenging document it is, but one valued by Constitutional scholars and worth study. As Rakove stresses, "Vices" is a "truly remarkable as well as historic document. For one thing, it marks one of those rare moments in the history of political thought where one can actually glimpse a creative thinker at work, not by reading the final published version of his ideas, but by catching him at an earlier point, exploring a problem in the privacy of his study."4 (7 pp.)

Discussion Questions

- What did these Founders consider the greatest defects of the Articles of Confederation? Why?

- What recommendations did they make for amending (or abandoning) the Articles?

- Why were they so alarmed by Shays's Rebellion and other farmers' uprisings in 1786-87? Weren't the uprisings examples of democracy in action?

- What dire predictions did Washington make about the nation's future if the Articles were not amended or abandoned? What predictions did Madison make?

- How did the two men's experiences influence their predictions and recommendations for the nation's future?

- Why did they and other Founders fear the inaction of "wise & good men" while unrest and violence escalated in the nation?

- What was at stake for the world if the U.S. failed so early in its existence?

- Elaborate on these Founders' statements about government by researching the conflicts between Congress and the states under the Articles of Confederation. How does each statement reflect provisions incorporated into the Constitution of 1787?

- – That power which holds the purse strings absolutely must rule.

Alexander Hamilton, 1780 - – He can have no right to the Benefits of Society who will not pay his Club towards the Support of it.

Benjamin Franklin, 1783 - – Thirteen Sovereignties pulling against each other, and all tugging at the federal head, will soon bring ruin on the whole . . . .

George Washington, 1786 - – . . . every Nation we read of have drank deep of the miseries which flow from despotism or licentiousness [excess of liberty]—the happy medium is difficult to practice.

Henry Lee, 1786 - – [Rebellion] is a medicine necessary for the sound health of government.

Thomas Jefferson, 1787 - – If the laws of the States were merely recommendatory to their citizens . . . what security, what probability would exist that they would be carried into execution?

James Madison, 1787

- – That power which holds the purse strings absolutely must rule.

- In "Vices," what did Madison identify as the major defects of the national and state governments under the Articles of Confederation?

- How did he differentiate the behavior of men [mankind] in groups and as individuals? Why did this matter in his political theory?

- How did he differentiate between the conduct of government in small and large communities? Why did this matter in his political theory?

- In "Vice" #11, how did Madison dispute the political ideal that "the majority who rule in such [representative] Governments are the safest Guardians both of public Good and of private rights"?

- What did Madison propose as protection from a tyranny of the majority?

- Compose an entry for Madison's final "vice"—Impotence of the law of the States—which he did not complete. What would he have stressed in this last item to conclude his memorandum for George Washington?

Framing Questions

- How did Americans' concept of self-governance change from 1776 to 1789? Why?

- How did their emerging national identity affect this process?

- What divisions of political ideology coalesced in this process?

- How did the process lead to the final Constitution and Bill of Rights?

- How do the Constitution and the Bill of Rights reflect the ideals of the American Revolution?

Printing

Founders on the defects of the Articles of ConfederationMadison, "Vices of the Political System of the United States"

TOTAL

8 pp.

7 pp.

15 pp.

Supplemental Sites

- – Text & overview (National Archives)

- – Historical overview (National Park Service)

- – Brief item-by-item comparison with Constitution (Steven J. J. Mount)

Annapolis Convention, 1786, overview (Maryland Historical Society, et al.)

- – Report (Avalon Project, Yale)

James Madison, The Federalist #10, 22 November 1787 (National Archives)

George Washington and the Constitution, by Prof. Theodore J. Crackel, University of Virginia, History Now, September 2007 (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

George Washington: The Making of the Constitution, 1784-1788, brief correspondence selections (University of Virginia)

On Shays's Rebellion of 1786

- – Shays' Rebellion and the Making of a Nation (Springfield Technical Community College, et al.)

- – 1798 commentary by William Manning (History Matters)

Teaching the Revolution, valuable overview essay by Prof. Carol Berkin, Baruch College (CUNY)

General Online Resources

1 Edmund S. Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763-89 (The University of Chicago Press, 1956, 3d. ed., 1992), p. 126.

2 Jack Rakove, "James Madison and the Constitution," History Now, September 2007 (Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History).

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

Images:

– The Articles of Confederation, p. 1 (detail). Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives.

– Charles Willson Peale, oil portrait of George Washington, 1787. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, bequest of Mrs. Sarah Harrison (The Joseph Harrison Jr. Collection), 1912.14.3; reproduced by permission.

– Charles Willson Peale, oil portrait of James Madison, 1792. Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 0126.1006; reproduced by permission.

– James Madison, handwritten notes entitled "Vices of the Present System of the United States," April 1787, p. 1 (detail). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, The Papers of James Madison.

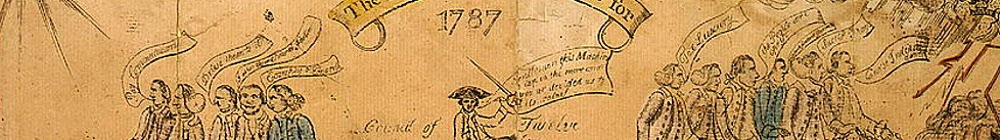

Banner image: Amos Doolittle, The Looking Glass for 1787, engraving, cartoon on the Connecticut ratification debates, 1787 (detail). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC4-1722.

*PDF file - You will need software on your computer that allows you to read and print Portable Document Format (PDF) files, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you do not have this software, you may download it FREE from Adobe's Web site.