REBELLION: 1775-1776

8. Declaring Independence

- The Declaration of Independence, 4 July 1776, annotated PDF

- Delegates' letters on the Declaration, July 1776 PDF

- News accounts of celebrations of the Declaration, 1776 PDF

- A Loyalist's rebuttal of the Declaration, Thomas Hutchinson, Strictures Upon the Declaration . . . , 1776, selections PDF

David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, 1789

How did the Declaration of Independence convince many Americans that independence, which they "first dreaded as an evil," was in truth a "national blessing"? Although fullscale war had erupted a year earlier—several coastal towns were nearly destroyed by early 1776—many Americans still hoped for reconciliation with Britain. After all, casting yourselves free from over two centuries of cultural heritage and political bonds to create a thin little coastal corridor of a nation—with big BRITAIN to the north and west and big SPAIN to the south and west—was a glorious goal, perhaps, but to many seemed nothing short of folly.

Two documents of inestimable influence spurred many Americans to commit to independence—Thomas Paine's Common Sense of January 1776, which we considered in the last section, and the Declaration of Independence, written primarily by Thomas Jefferson and adopted in July 1776 by the Second Continental Congress. Both documents stressed the absolute necessity of independence: that no other option was left to preserve American rights and liberty. And each document addressed the front-and-center question: How do we justify this unprecedented action to our fellow Americans, Britain, and the world? Remember that the American Revolution was the first of many wars for independence over the next two hundred years, and even ardent Patriots understood the obligation to present their cause as just and honorable—as a long-considered action by reasonable men.

The Declaration of Independence, 4 July 1776, annotated. When in the Course of human events. All men are created equal. Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. Within the Declaration of Independence are some of the most renowned phrases in American history, redolent of unified purpose and national identity. In later years the Declaration would come to signify America—as a beacon of resistance to tyranny, a model of self-definition, and proof that ideas have consequences. In the summer of 1776, however, the Declaration had a very immediate and local charge. "Above all else," writes scholar Stephen Lucas, "the Declaration had to consolidate support for independence among the colonists. It had to present the case for independence so powerfully, so judiciously, so eloquently as to rally those Americans already committed to independence and to convince what Samuel Adams called the 'timid' and the 'doubting' of its justice and necessity. Its impact on mankind in general would be of little consequence if it failed to do its job in America"1 [emphasis added]. How did the Declaration accomplish this? How did it inspire confidence as well as solidarity? How does it differ from Thomas Paine's Common Sense, published six months earlier? We recommend that you read the Declaration aloud and/or listen to online recitations (see audio links below). Don't rush through the list of grievances; they are purposely cadenced to be riveting and convincing. For classroom use, the twenty-seven grievances have been briefly explained in this text. (5 pp.)

Delegates' letters on the Declaration, July 1776. Delegates' letters in the fateful month of July 1776 reveal their sense of accomplishment, trepidation, and readiness to face the consequences of their decision. Selections from seven delegates' letters are presented here, concluding with an excerpt from Thomas Jefferson's final letter, written in 1826, in which he declined the invitation to attend the fiftieth-anniversary celebration of the Declaration. What immediate sentiments are reflected in the letters? How might Jefferson and Adams, who died on the Declaration's fiftieth anniversary, have commented in 1826 on the delegates' letters of July 1776? (6 pp.)

News accounts of celebrations of the Declaration, 1776. Exuberant official celebrations were held throughout the colonies in which the Declaration was read to the public, the new states' military preparedness was put on display, symbols of British authority were destroyed with much "huzzaing," and afterwards, much convening occurred in taverns to drink "patriotic toasts" that might appear in the next week's newspapers. How did the celebrations (and the reporting of them) mark a clear transition from British colonies to the status of free and independent states? How did they forge unity among the colonists? (3 pp.)

A Loyalist's rebuttal of the Declaration, Thomas Hutchinson, Strictures Upon the Declaration . . . , 1776, selections. As scholar Stephen Lucas reminds us, "the Declaration presented the truth as Jefferson and the Congress saw it, but it is the last place one should look for an evenhanded account of the American Revolution. Nor should one expect to find such an account in the writings of administration apologists like [John] Lind and [Thomas] Hutchinson."2 Still, we should give the "apologists" a hearing, in this case Thomas Hutchinson, a Boston-born Loyalist who served as the last royal governor of Massachusetts from 1771 until 1774, when he took exile in Britain and was replaced by a military governor. Not entirely unsympathetic to the colonists' grievances, he had yet enforced all parliamentary actions and upheld British authority. In late 1776 in London, Hutchinson published a 32-page anonymous essay entitled Strictures Upon the Declaration of the Congress at Philadelphia, dismissing the Declaration as a "list of imaginary grievances." Overall, how does Hutchinson reject the legitimacy of the Declaration? How would the Declaration authors and signers have replied? (9 pp.)

Discussion Questions

- Summarize the content of the Declaration in a three-to-five sentence overview. Basically, what is the Declaration declaring?

- How does the preamble justify America's decision to throw off one government and create another? What part of the justification is "self-evident"? What part must be explained?

- Organize the 27 grievances into three to five groups. Clearly explain the pattern among the groups, e.g., by type of rights violation, severity or frequency of grievance, extent of colonial opposition. What do you discover in the process of organizing the grievances?

- Why are the grievances not listed in chronological order, with dates and events?

- Analyze the structure of the Declaration. How does it give momentum and necessity to the Declaration?

- – introduction (first sentence)

- – preamble ("We hold . . . future security")

- – list of 27 grievances against King George III and Parliament

- – final statement to the British people

- – conclusion ("We, therefore . . . sacred Honor")

- Analyze the rhetoric of the Declaration (see Lucas essay, in supplemental sites). In what ways is the final Declaration more or less persuasive, in your analysis, than Jefferson's draft?

- How does the Declaration inspire confidence as well as solidarity?

- How does the cadence of the grievance list contribute to the urgency and certainty of the Declaration?

- Why did the delegates remove Jefferson's clause on the slave trade from the grievance list? (See REBELLION #6: The Enslaved.)

- Overall, how did the Declaration convince many Americans that independence, which they "first dreaded as an evil," was in truth a "national blessing"? [Ramsay, 1789]

- Compare Common Sense and the Declaration of Independence by content, structure, and rhetoric. How did such different documents by different men address similar issues?

- How did each try to convert the "timid" and the "doubting" (in Samuel Adams's words) to the cause of independence? How had circumstances changed in the six months between the two documents (January and July 1776)?

- What variety of sentiments is evident in the July 1776 letters by delegates to the Second Continental Congress?

- How did delegate Robert Morris explain his opposition to the Declaration—and his decision to support it once adopted?

- How might Jefferson and Adams, who died on the Declaration's fiftieth anniversary, have commented in 1826 on the delegates' sentiments in 1776?

- Describe the colonies' official readings and celebrations of the Declaration. How did they mark a clear transition from "British colonies " to "free and independent states"? How did they forge unity and certainty?

- How does the list of "patriotic toasts" in the Massachusetts Spy reflect the process of solidifying revolutionary fervor and readiness for war?

- Why is it stressed in news accounts of the celebrations that all was conducted in "decency and good order"?

- Write an introduction to the Declaration of Independence for a person becoming naturalized as a U.S. citizen. Begin with one of these statements from the readings, or choose another.

- – Samuel Adams: Our Declaration of Independency has given Vigor to the Spirits of the People.

- – John Adams: I am well aware of the Toil and Blood and Treasure that it will cost Us to maintain this Declaration, and support and defend these States. Yet through all the Gloom I can see the Rays of ravishing Light and Glory. I can see that the End is more than worth all the Means.

- – William Ellery: . . . for it is One Thing for Colonies to declare themselves independent and another to establish themselves in Independency.

- – The Pennsylvania Packet: The declaration of Independence was this day proclaimed here . . . The people are now convinced of what we ought long since to have known, that our enemies have left us no middle way between perfect freedom and abject slavery. [15 July 1776]

- – The Declaration of Independence: "these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown."

- Overall, how does Loyalist Thomas Hutchinson reject the legitimacy of the Declaration? Why does he dismiss it as a "list of imaginary grievances"?

- To whom is his rebuttal addressed? Why is he so angry?

- Why did the full Congress remove much of the anger (but not all) from Jefferson's draft of the Declaration? (See comparison of versions, in supplemental sites.)

- How would Declaration signers have replied to Hutchinson's rebuttal, especially John Adams, Samuel Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and its primary author, Thomas Jefferson?

Framing Questions

- What rebellions and "civil wars" occurred within the colonies as war approached in the mid 1770s?

- How did colonists express and debate their differing opinions?

- How did they deal with political opponents?

- What caused the moderate voice to fade from the political arena?

- What led Americans to support or oppose the ultimate goal of independence?

Printing

The Declaration of Independence (annotated)Delegates' letters on the Declaration

Celebrating the Declaration: news accounts

A Loyalist's rebuttal of the Declaration

TOTAL

5 pp.

6 pp.

3 pp.

9 pp.

23 pp.

Supplemental Sites

- – John F. Kennedy, 1957 (The New York Times/WQXR)

- – Bill Barker (Monticello)

- – National Public Radio broadcasting staff, 2009 (NPR)

Comparison of three versions of the Declaration—rough draft, reported copy, engrossed copy (Independence Hall Association, Philadelphia)

Declaration of Independence, online exhibition: Thomas Jefferson (Library of Congress)

Source documents, June 1776 (The Founders' Constitution, University of Chicago Press & the Liberty Fund)

- – Preamble, Virginia Constitution, written by Jefferson

- – Virginia Declaration of Rights, written by George Mason

- – Search The Founders Constitution for other source documents.

- – Declaration of Independence, teacher's guide, including material on Locke's 1689 treatises on government

- – The World in 1776

- – The Road to Revolution (Q&A game)

"Was the American Revolution Inevitable?," not-to-miss teachable essay by Prof. Francis D. Cogliano, University of Edinburgh (BBC)

Teaching the Revolution, valuable overview essay by Prof. Carol Berkin, Baruch College (CUNY)

General Online Resources

1Stephen E. Lucas, "Justifying America: The Declaration of Independence as a Rhetorical Document," in American Rhetoric: Context and Criticism, ed. Thomas W. Benson (Southern Illinois University Press, 1989), p. 81.

2 Ibid., p. 100. John Lind's 110-page rebuttal of the Declaration, published like Hutchinson's in 1776 in London, was entitled An Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress.

Images:

– Declaration of Independence, broadside, n.p., July 1776 (detail). Reproduced by permission of the New-York Historical Society. Digital image accessed through Early American Imprints, Doc. 43196, American Antiquarian Society with Readex/NewsBank.

– Charles Willson Peale, portrait of Thomas Jefferson, oil on canvas, 1791. Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia, National Park Service, INDE11883. Reproduced by permission.

– John Singleton Copley, portrait of Samuel Adams, oil on canvas, ca. 1772 (detail), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; deposited by the City of Boston, L-R 30.76c. Reproduced by permission.

– John Trumbull, portrait of John Adams, oil on canvas, 1793 (former attribution: Gilbert Stuart). National Gallery of Art (Smithsonian Institution), NPG 75.52. Reproduced by permission.

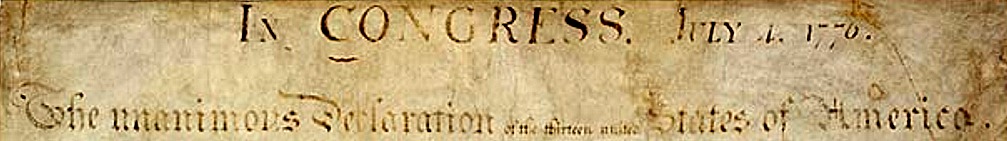

Banner image: Original Declaration of Independence, parchment, 1776 (detail); on exhibit in the Rotunda of the National Archives, Washington, DC. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

*PDF file - You will need software on your computer that allows you to read and print Portable Document Format (PDF) files, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you do not have this software, you may download it FREE from Adobe's Web site.