CONSTITUTION: 1787-1791

7. Portraying the Founders

- Portraits (11) of the Founders in a transitional era, 1780-early 1790s PDF

- Commentary on the death of Benjamin Franklin, 1790 PDF

Gordon S. Wood, Revolutionary Characters: What Made the Founders Different (2006)1

From the earliest days of the independent United States, Americans have looked back to its founding—to honor it and to define it for posterity. During the Revolution, countless addresses, sermons, and parades commemorated the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and other events of the nation's founding. As the contributions of the uniquely civic-minded men who formed the nation became widely known—and held in due awe—the nation began to commemorate its founders. We conclude this section, and this primary source collection, by looking at the earliest portrayals of the Founders, from the end of the Revolutionary War to the first years under the U.S. Constitution. How have the portrayal and commemoration of the Founders evolved over the centuries to our day?

Portraits (11) of the Founders in a transitional era, 1780-early 1790s.

The familiar portraits of the Founders do not include the likenesses above, painted as the nation floundered under the Articles of Confederation and began anew under the Constitution. The famous and oft-produced portraits come from later, more confident years when Founders served as the first five presidents—Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe—and as cabinet members, such as Alexander Hamilton. Only Franklin's portrait from 1785 portrays the iconic image Americans hold of the oldest Founding Father, who died in 1790 at age 84. Presented in this collection are eleven portraits from 1780, when the Revolutionary War was still unwon, to the early 1790s, when the nation began to solidify under Washington's presidency. Six of the portraits were painted by the renowned Charles Willson Peale (himself a Revolutionary War veteran), many for the portrait gallery of Revolutionary heroes in his Philadelphia museum—portraits composed to embody the virtue and resolve that had created the new nation and to serve as inspiration to its citizens. (6 pp.)

The familiar portraits of the Founders do not include the likenesses above, painted as the nation floundered under the Articles of Confederation and began anew under the Constitution. The famous and oft-produced portraits come from later, more confident years when Founders served as the first five presidents—Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe—and as cabinet members, such as Alexander Hamilton. Only Franklin's portrait from 1785 portrays the iconic image Americans hold of the oldest Founding Father, who died in 1790 at age 84. Presented in this collection are eleven portraits from 1780, when the Revolutionary War was still unwon, to the early 1790s, when the nation began to solidify under Washington's presidency. Six of the portraits were painted by the renowned Charles Willson Peale (himself a Revolutionary War veteran), many for the portrait gallery of Revolutionary heroes in his Philadelphia museum—portraits composed to embody the virtue and resolve that had created the new nation and to serve as inspiration to its citizens. (6 pp.)Commentary on the death of Benjamin Franklin, 1790. Benjamin Franklin's death on April 17, 1790, was the nation's first loss of a Founding Father. In failing health and unremitting pain for several years, Franklin had given his last service to his country as a delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. The Philadelphia printer, author of Poor Richard's Almanac, signer of the Declaration of Independence and of the U.S. Constitution, longtime representative to Britain and France, a skillful negotiator of the peace treaty finalizing American independence, Franklin was buried in the Philadelphia Christ Church Burial Ground, next to his wife Deborah and near his son Folger who had died of smallpox as a child. Presented here are reports and tributes delivered in the two months after his death. What did they emphasize about Franklin as a man, a citizen, a pursuer of knowledge, and as a Founder of his country? To what extent did they set a precedent for mourning the nation's Founders? (6 pp.)

Discussion Questions

- Overall, how were the Founders represented in the transitional period from 1780 to the early 1790s?

- How does each portrait exhibit the purpose for which it was painted?

- What is conveyed through pose, gaze, expression, demeanor, and costume?

- In its first decades, how did the nation envision itself through the depiction of its revered Founders?

- How do these portraits differ from later, more well-known portraits of the men, especially the presidential portraits of Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison? (See Supplemental Sites.)

- Which painting is most effective for you, as a viewer? Why?

- For each pair or group of portraits, consider these questions:

- – Are the portraits by the same or different artists?

- – Are the portraits from life?

- – Why were they painted?

- – What was occurring in the person's life at the time of each portrait?

- Compare the Washington portraits (1787-90) in this collection with three earlier portraits (1779-85). How do they mark a transition from General Washington to President Washington?

- View and compare a wide selection of Charles Willson Peale portraits of American leaders [links below from multiple sites]. What is distinctive about Peale's portraits? What attributes did he strive to capture in his portraits?

- John Adams, 1791-94

- Benjamin Franklin, 1785

- Alexander Hamilton, ca. 1780

- Alexander Hamilton, ca. 1790-1795

- Thomas Jefferson, 1791

- Henry Lee, 1782

- James Madison, 1783

- James Madison, 1792

- Thomas Mifflin, 1784 portrait, 1795)

- Gouverneur Morris & Robert Morris, 1783

- David Rittenhouse, 1791

- David Rittenhouse, ca. 1795

- Benjamin Rush, 1783 & 1786

- George Washington, 1772

- George Washington, 1776

- George Washington, 1777

- George Washington, 1779

- George Washington, 1779-81

(replica by Peale)

- George Washington, 1787

- George Washington, 1795-98

(Peale replica of last life

portrait, 1795)

- What attributes of Franklin were honored in the memorial tributes? What accomplishments?

- What was emphasized about Franklin as a man, a citizen, a pursuer of knowledge, and as a Founder of his country?

- In what ways did he model the ideal American citizen?

- How was the usefulness of his life emphasized (in addition to his serving as a role model)?

- How were his religious views described? his use of reason?

- What did you learn about Franklin from the reports and tributes?

- Why do you think Franklin's scientific pursuits were emphasized in the tributes?

- Why do you think his role as a signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution was unmentioned in the tributes?

- Why do you think his diplomatic achievements in Europe were underplayed in the tributes?

- To what extent did the 1790 Franklin tributes set a precedent for mourning the nation's Founders?

- Why did President Washington decide against directing the executive branch to wear official mourning (a black armband) for Franklin?

- Compare the tributes to Franklin—the first Founding Father to die—with those on the deaths of George Washington (Dec. 4, 1799), Alexander Hamilton (July 12, 1804), Thomas Jefferson (July 4, 1826), John Adams (July 4, 1826), and James Madison (June 28, 1836). How do the tributes exhibit the evolving image of a Founding Father?

- How have the portrayal and commemoration of the Founders, and of the nation's founding, evolved over the centuries to our day?

- To conclude this section—and this primary source collection—consider this statement by historian Gordon S. Wood in his Revolutionary Characters: What Made the Founders Different. Compose an essay, newspaper editorial, dialogue, political cartoon, drawing or other creation that distills Wood's point and conveys your interpretation of the Founders for our time.

America's Founding Fathers, or the founders, as our antipatriarchal climate now prefers, have a special significance for Americans. Celebrating in the way we do this generation that fought the Revolution and created the Constitution is peculiar to us. No other major nation honors its past historical characters, especially characters who existed two centuries ago, in quite the manner we Americans do. We want to know what Thomas Jefferson would think of affirmative action, or George Washington of the invasion of Iraq. The British don't have to check in periodically with, say, either of the two William Pitts the way we seem to have to check in with Jefferson or Washington. We Americans seem to have a special need for these authentic historical figures in the here and now. Why should this be so?

. . . The identities of other nations, say, being French or German, are lost in the mists of time and usually taken for granted. . . . But Americans became a nation in 1776, and thus, in order to know who we are, we need to know who our founders are. The United States was founded on a set of beliefs and not, as were other nations, on a common ethnicity, language, or religion. Since we are not a nation in any traditional sense of the term, in order to establish our nationhood, we have to reaffirm and reinforce periodically the values of the men who declared independence from Great Britain and framed the Constitution. As long as the Republic endures, in other words, Americans are destined to look back to its founding.

Gordon S. Wood, Revolutionary Characters: What Made the Founders Different

(New York: Penguin Press, 2006), pp. 3-4.

Framing Questions

- How did Americans' concept of self-governance change from 1776 to 1789? Why?

- How did their emerging national identity affect this process?

- What divisions of political ideology coalesced in this process?

- How did the process lead to the final Constitution and Bill of Rights?

- How do the Constitution and the Bill of Rights reflect the ideals of the American Revolution?

Printing

Portraits of the Founders, 1780-early 1790sOn the death of Benjamin Franklin

TOTAL

6 pp.

6 pp.

12 pp.

Supplemental Sites

- – George Washington, 1795, by Gilbert Stuart (Vaughn type) (National Portrait Gallery)

- – George Washington, 1796, by Gilbert Stuart (Lansdowne portrait) (National Portrait Gallery)

- – John Adams, 1800/1815, by Gilbert Stuart (National Gallery of Art)

- – Thomas Jefferson, 1801/1825, by Gilbert Stuart (National Portrait Gallery)

- – James Madison, 1816, by John Vanderlyn (Wikipedia)

- – Portraits of the Presidents from the National Portrait Gallery

- – George and Martha Washington: Portraits from the Presidential Years

- – George Washington: A National Treasure (the Lansdowne Portrait by Gilbert Stuart)

- – Franklin and His Friends: Portraying the Man of Science in Eighteenth-Century America

- – Joseph-Siffred Duplessis

- – Charles Willson Peale

- – Robert Edge Pine

- – Edward Savage

- – Gilbert Stuart

- – John Trumbull

Explore John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence (Seattle Art Museum)

Artifacts related to Franklin's death (Library of Congress)

Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World (Franklin Tercentenary Committee)

Benjamin Franklin, interactive timeline (Franklin Tercentenary Committee)

Benjamin Franklin, timeline (The Franklin Institute)

"Was the American Revolution Inevitable?," not-to-miss teachable essay by Prof. Francis D. Cogliano, University of Edinburgh (BBC)

Teaching the Revolution, valuable overview essay by Prof. Carol Berkin, Baruch College (CUNY)

General Online Resources

1Gordon S. Wood, Revolutionary Characters: What Made the Founders Different (New York: Penguin Press, 2006), p. 4.

Images:

– George Washington, life portrait by Charles Willson Peale, oil on canvas, 1787. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Bequest of Mrs. Sarah Harrison (The Joseph Harrison, Jr., Collection), 1912.14.3; reproduced by permission.

– Thomas Jefferson, miniature portrait (from original painted from life) by John Trumbull, oil on mahogany, 1788. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Cornelia Cruger, 1923, 24.19; reproduced by permission.

– James Madison, miniature portrait from life by Charles Willson Peale, watercolor on ivory in gold case, presented in velvet-lined container, 1783. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Rare Books & Special Collections; photo: LC-USZC4-4097.

– Alexander Hamilton, life portrait by Charles Willson Peale, oil on canvas, ca. 1790-1795. Independence National Historical Park, INDE11877; reproduced by permission.

– Benjamin Franklin, life portrait by Charles Willson Peale, oil on canvas, 1785. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1912.14.2; reproduced by permission.

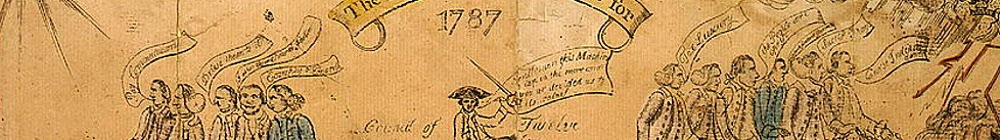

Banner image: Amos Doolittle, The Looking Glass for 1787, engraving, cartoon on the Connecticut ratification debates, 1787 (detail). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC4-1722.

*PDF file - You will need software on your computer that allows you to read and print Portable Document Format (PDF) files, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you do not have this software, you may download it FREE from Adobe's Web site.