REBELLION: 1775-1776

3. Loyalists III: Join—or Else

- On the treatment of Loyalists in Virginia, travel journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777, selections PDF

- On the treatment of Loyalists in North Carolina, travel letters of Janet Schaw, 1775, selections PDF

Nicholas Cresswell, 1774

What the British travellers Nicholas Cresswell and Janet Schaw witnessed in America that inspired their grim appraisals was the harsh and uncompromising enforcement of loyalty to the Patriot cause, often pursued through intimidation, threats, and violence. After the First Continental Congress initiated a boycott of British goods in late 1774, Patriot "Committees of Safety" were created in all the colonies, and one of their first tasks was to gather signed pledges of support for Congress and the boycott. Insisting on one-hundred-percent support, the Committees threatened Loyalists and the uncommitted with ostracism, loss of property, and physical harm. They were "often self-appointed and usually composed of the Sons of Liberty," writes historian Catherine S. Crary, whose purpose "was not justice or a regard for civil rights, but rooting out Loyalists and blocking their support of the British cause."1 What the Congress had promoted to spur a united front in demanding Americans' rights from Britain soon degenerated into mass violations of the rights of Loyalists or wavering citizens. Here we see the workings of the Committees of Safety as described by two British travellers in the southern colonies.

On the treatment of Loyalists in Virginia, travel journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777, selections. An Englishman travelling in the British Atlantic colonies, Cresswell found himself in Virginia in the volatile mid 1770s when clear-cut political allegiances became mandatory. Declare yourself—are you a Patriot or a Loyalist? Not only did Cresswell observe this process in horror, he was victimized by it, forced by the town Committee of Safety to stay in the colony while—he wasn't sure—they investigated him as a spy? tried to force him into the Patriot forces? He realized he would have to make his escape from America, which he did in 1777. While attributing some of the colonies' troubles to the British, Cresswell describes the calculated villainy of Patriot leaders and the puritanical fanaticism of some preachers as the chief causes of the turmoil that was setting the colonists against each other. In the name of liberty, colonial leaders have suppressed dissent and condoned the violent intimidation of Loyalists. Preachers have used religious prejudice to turn their followers against the king. Colonists who have awakened from their "delirium" are forced publicly to assent to the Patriots' rule but secretly curse it as slavery. "This country turned Topsy Turvy," he writes upon leaving, "changed from an earthly paradise to a Hell upon terra firma." (7 pp.)

On the treatment of Loyalists in North Carolina, travel letters of Janet Schaw, 1775, selections. Scotswoman Janet Schaw also witnessed the intimidation of Loyalists during a visit to North Carolina in 1775, where she observed a society that was splitting asunder under the stress of revolutionary politics. Zealous Patriots were forcing men and women along the Cape Fear River to take sides. They employed violence and intimidation and, Schaw suggests, even feigned a slave revolt to unite their countrymen in opposition to the British. Schaw recorded her impressions in travel letters that were compiled and published in 1921 as Journal of a Lady of Quality; Being the Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the Years 1774 to 1776. As its editor reminds us, "such contemporary evidence makes us realize that our forefathers, however worthy their object, were engaged in real rebellion and revolution, characterized by the extremes of thought and action that always accompany such movements, and not in the kind of parlor warfare described in many of our textbooks."2 (7 pp.)

Discussion Questions

- What led British visitors Cresswell and Schaw to their grim appraisals of the colonial situation in the mid 1770s?

- What policies of the Patriots do they condemn? what practices of the local Committees of Safety?

- How are Loyalists treated for their stance? What ultimatum are they given by the Committees of Safety?

- How are uncommitted colonists pressured into supporting the Patriot cause?

- According to Cresswell:

- – What role did colonists' personal debts to Britain play in the impending revolt?

- – How had "religious rascals" spurred the political divide?

- – Why would Americans "awake from their delirium" to reject the Patriot intimidation and yet remain silent and acquiescent?

- Why does he mention the Virginians' previous "cruelty to the innocent Quakers"? the slaveholder's callousness toward his slaves?

- Of what does he accuse the Patriot leaders in New England?

- What point does Cresswell make by referring to the Aesop fable "The Dog and the Shadow"?

- What point does Janet Schaw make by relating the Patriot officer's reading of Falstaff's speech in Henry IV?

- According to Janet Schaw:

- – Why was America a "land of nominal freedom and real slavery"?

- – How did local Patriots use the fear of slave insurrection to rally support for their cause?

- – Why were the rebellious colonists "devoted to ruin"?

- To what extent did Cresswell and Schaw feel in personal danger?

- Despite their experiences, what sympathies do Cresswell and Schaw express for the Americans? Why does Cresswell describe many colonists as "honest, well-meaning people"?

- What rights, guaranteed later in the U.S. Constitution, were violated by the Patriot Committees of Safety? (See, especially, Article I on habeas corpus, and Amendments 1-10, the Bill of Rights.)

- How would Patriot leaders such as John Adams, Samuel Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington have responded to the excesses of the Committees of Safety?

- Create a dialogue between Cresswell and Schaw. Choose the time and setting (perhaps Britain after their journeys, or imagine a letter correspondence while they are in America). In addition to presenting the similarities in their experiences, highlight their different perspectives due to their differences in class, gender, and sense of personal vulnerability.

- Write an overview for a British audience of the treatment of Loyalists in Virginia and North Carolina. Begin with one of the statements below, using it as the scaffold for your overview.

Nicholas Cresswell:

- – The people here are ripe for revolt.

- – I am now in an enemy's country, forbidden to depart.

- – I have seen this a happy Country and I have seen it miserable in the short space of three years.

- – Freedom of speech is what they formerly enjoyed but it is now a stranger in the Land.

- – Good heavens! What a scene this town is.

- – I became unable to move and absolutely petrified with horror.

- – Rebels, this is the first time I have ventured that word.

- – You [Patriots] are devoted to ruin, whoever succeeds.

Framing Questions

- What rebellions and "civil wars" occurred within the colonies as war approached in the mid 1770s?

- How did colonists express and debate their differing opinions?

- How did they deal with political opponents?

- What caused the moderate voice to fade from the political arena?

- What led Americans to support or oppose the ultimate goal of independence?

Printing

Nicholas Cresswell, travel journal, VirginiaJanet Schaw, travel letters, North Carolina

TOTAL

7 pp.

7 pp.

14 pp.

Supplemental Sites

Janet Schaw, Journal of a Lady of Quality . . . in the Years 1774 to 1776, full text in Documenting the American South (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library)

Which Side to Take: Revolutionary or Loyalist?, North Carolina (Learn NC, UNC-Chapel Hill)

The White Loyalists of Williamsburg (Kevin P. Kelly; Colonial Williamsburg)

"Was the American Revolution Inevitable?," not-to-miss teachable essay by Prof. Francis D. Cogliano, University of Edinburgh (BBC)

Teaching the Revolution, valuable overview essay by Prof. Carol Berkin, Baruch College (CUNY)

General Online Resources

1Catherine S. Crary, ed., The Price of Loyalty: Tory Writings from the Revolutionary Era (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1973), pp. 55-56.

2 Evangeline Walker Andrews, Introduction to Journal of a Lady of Quality; Being the Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the Years 1774 to 1776, 1921, p. 9; electronic edition, Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library, at docsouth.unc.edu/nc/schaw/schaw.html.

Images:

– Portrait of Nicholas Cresswell by an unidentified artist, ca. 1780. Reproduced by permission of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

– South Carolina association pledge adopted by the Provincial Congress, 11 May 1775, broadside, 1775 (detail). Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Manuscripts & Archives Division. Digital image accessed through Early American Imprints, Doc. 42942, American Antiquarian Society with Readex/NewsBank.

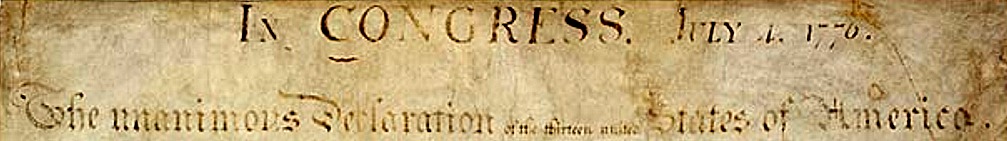

Banner image: Original Declaration of Independence, parchment, 1776 (detail); on exhibit in the Rotunda of the National Archives, Washington, DC. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

*PDF file - You will need software on your computer that allows you to read and print Portable Document Format (PDF) files, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you do not have this software, you may download it FREE from Adobe's Web site.