REBELLION: 1775-1776

1. Loyalists I: Civil War

- Loyalists at the outbreak of war: selections from letters and commentary, 1775-1776 PDF

- A Loyalist's poem: Rev. Myles Cooper, "The Patriots of North America," 1775, selections PDF

Gov. William Franklin, address to the

New Jersey Assembly, 1775

In the 1770s the term civil war, not revolution, was used to describe the spectre of outright war with Britain. After all, it was a conflict within the British empire, between the mother country and its colonies over internal issues of rights and power. Often lost in a study of the Revolution are the "horrors of civil war" among Americans themselves—among supporters of independence (Patriots/Whigs), opponents (Loyalists/Tories), and the ambivalent Americans who were angry with Britain but opposed to declaring independence. In this theme, REBELLION, we explore several aspects of these "civil wars" as resistance evolved into full rebellion by the self-declared "free and independent States . . . absolved of all allegiance to the British Crown."

- – Sections 1-4 consider the civil war between Patriots and Loyalists, focusing on the Loyalist experience at the outbreak of war. For most Loyalists, writes historian Catherine Crary, "Loyalism was an evolutionary and painful process, even as the transfer of allegiance to a new government was not easy for many rebels."1

- – Section 5 views the struggles of religious pacifist groups, primarily in Pennsylvania, as they sought tolerance for

their beliefs as conscientious objectors to war.

- – Section 6 examines the debate over slavery at a time when white men, including slaveholders, were demanding their "natural rights" and declaring that "all men are created equal."

- – Sections 7-8 focus on the critical year of 1776 when many Americans made a final irrevocable transition. They abandoned hope for reconciliation with Britain and embraced the radical goal of independence from Britain. Two documents of inestimable influence encompass this transition—Thomas Paine's Common Sense of January 1776 and the Declaration of Independence of July 1776. Both documents strove to convince uncertain Americans of the absolute necessity of independence: that no other option existed for preserving their rights and liberty.

We begin with an overview of the Loyalist experience in 1775-76 as the political divide hardened, mutual recriminations escalated, and no moderate voices were tolerated. Note: Loyalist political writings are included in Theme I: CRISIS; Theme II: REBELLION, #7, 8; Theme III: WAR, #2, 7, 8; and Theme IV: INDEPENDENCE, #2, 4. See the chronological all-texts list.

Loyalists at the outbreak of war: selections from letters and commentary, 1775-1776. After the Battle of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, any toleration for Loyalists vanished. Patriot Committees of Safety required citizens to pledge support for the cause of American independence or be deemed "inimical to the liberties of America." Violence toward Loyalists increased, leading many to leave the country for Canada, Britain, or the West Indies. "For these British subjects living on the American side of the Atlantic," writes historian Crary, "the struggle was a bitter civil war with the issue cutting across lines of family, of friendships, of neighbors, and even of husbands and wives. Some saw the issue from Parliament's point of view, some from the radical point of view, and a large segment from a neutral position deriving from judiciousness, inertia, or a delusive hope that the storm would pass them by."2 Presented here are selections by and about Loyalists that illustrate this political maelstrom and the wrenching personal decisions required of Americans loyal to Britain and/or unwilling to abandon reconciliation and adopt separation. What range of opinion and emotion is displayed? What range of certainty and ambivalence? To what extent was this political divide a "civil war"? (6 pp.)

A Loyalist's poem: Rev. Myles Cooper, "The Patriots of North America," 1775, selections. If you were a Loyalist in America in the 1770s, you tried to explain to yourself and others why your Patriot neighbors were turning the paradise of America into "an endless Hell" by objecting to what was, in your view, the benign, enlightened, and gentle rule of Great Britain. Such sentiments motivated Loyalist Myles Cooper to publish anonymously a 34-page poem in 1775 titled The Patriots of North America, in which he accuses them of committing "treason in mask of liberty." To Cooper, an English-born Anglican clergyman and president of Kings College (Columbia University) in New York City, the colonists were led astray by proud ignorant fanatics or, as he calls them in his poem, "this vagrant Crew / Whose wretched Jargon, crude and new / Whose Impudence and Lies delude / The harmless, ign'rant Multitude." Cooper's rhetoric grows more frenzied as he delivers verse after verse condemning Patriot leaders for their frenzied rhetoric. As such, the poem is a stark example of the hardened political divide in 1775. Cooper's satire drips with condescension and disdain, but even so he summons enough sympathy to lament the tragedy of a civil war:

See Friends, Companions, once belov'd,

By dire contagious Madness mov'd;

Frantic, and ruthless, pierce the Breasts,

Once with dear, mutual Love possest.In summer 1775 Cooper fled an angry mob to seek refuge on a British ship in New York harbor and soon sailed for England, permanently. What does Cooper's poem reveal about the political atmosphere in 1775? Why is he so angry? How would other Loyalists, including other Anglican clergymen like Rev. Caressing, respond to his satire? How would Patriot leaders respond? For whom is the poem intended? (5 pp.)

Discussion Questions

- From the evidence of these documents, characterize the political atmosphere in America in 1775-1776.

- How would Patriots and Loyalists differ in describing the political atmosphere in which they vied for influence?

- In what ways was the political divide a civil war?

- What range of opinion and emotion is displayed in the texts? What range of certainty and ambivalence?

- What factors led some Loyalists to flee America and some to remain?

- On what did Loyalists blame the rupture with Britain?

- What appears to motivate Cooper's satire and contempt in his poem? For whom is the poem intended?

- How does he portray the rebellious colonists as petulant ungrateful children? Explain his anti-common-man invectives.

- How does he portray the Patriot leaders as power-hungry ignoramuses? as propagandists guilty of treason?

- What does Cooper mean by imploring "In Freedom live, for Freedom die; / But Oh! instruct them first to know, / Tyrants from Sov'reigns, Friend from Foe"?

- How would other Loyalists respond, including other Anglican clergymen represented in these readings? (See selections from Anglican anti-rebellion sermons in Theme I: CRISIS.)

- Judging from the readings by John Adams and Benjamin Franklin in this primary source collection, how would they respond to Cooper's poem? to the statements of Loyalists on leaving America? to Henry Laurens's appeal for tolerance toward Loyalists?

- Write an essay, newspaper account, or revolutionary-era broadside on the Loyalist position in 1775-1776, using one of these statements from the texts as your focus and starting point:

- – You have now pointed out to you, Gentlemen, two Roads—one evidently leading to Peace, Happiness and a Restoration of the public Tranquility—the other inevitably conducting you to Anarchy, Misery, and all the Horrors of a Civil War.__William Franklin, governor of New Jersey & Loyalist, 1775

- – I leave America, and every endearing connection, because I will not raise my hand against my Sovereign—nor will I draw my sword against my Country.__Isaac Wilkins, Loyalist, 1775

- – I say, Gentlemen, there are certain Men who are not Enemies to their Country—who are friends to all America . . . they acknowledge that we are greatly aggrieved & oppressed—they wish well to our Cause— . . . [but] they cannot, they dare not, for many reasons subscribe to the Association [Patriot pledge].__Henry Laurens, Patriot, 1775

- – Triumphant Crimes pollute the Land,

Consign'd to ev'ry Butcher's Hand;

Spread Desolation like a Flood,

And Brothers shed their Brother's Blood.__Rev. Myles Cooper, 1775 - – I . . . wish that Conciliatory Measures may Speedily take place or total Ruin and Destruction will soon follow, and America Lost and Gone.__James Wright, governor of Georgia, 1775

- – I don't believe there ever was a people in any age or part of the World that enjoy'd so much liberty as the people of America did under the mild indulgent Government (God bless it) of England and never was a people under a worser state of tyranny than they are at present.__Sylvester Gardiner, Loyalist, 1776

- – You have now pointed out to you, Gentlemen, two Roads—one evidently leading to Peace, Happiness and a Restoration of the public Tranquility—the other inevitably conducting you to Anarchy, Misery, and all the Horrors of a Civil War.

- Combine one of the statements in #13 with one from the Patriot statements in 1776 (see Discussion Questions for Sections 8 and 9), and compose a dialogue between a Loyalist and a Patriot. What point of dispute will you emphasize?

- Did the political divides of 1775-1776 make the revolution more or less likely?

Framing Questions

- What rebellions and "civil wars" occurred within the colonies as war approached in the mid 1770s?

- How did colonists express and debate their differing opinions?

- How did they deal with political opponents?

- What caused the moderate voice to fade from the political arena?

- What led Americans to support or oppose the ultimate goal of independence?

Printing

Loyalists at the outbreak of the RevolutionCooper, The Patriots of North America, poem

TOTAL

6 pp.

5 pp.

11 pp.

Supplemental Sites

DBQ on the Loyalist-Patriot divide (historyteacher.net, Susan Pojer)

"What is a Loyalist?: The American Revolution as Civil War," by Edward Larkin, Common-Place: The Interactive Journal of Early American Life, August 2007 (American Antiquarian Society with the University of Oklahoma)

Rev. Myles Cooper, biography (Columbia University)

The American Revolution, overviews and primary sources (American Memory, Library of Congress)

- – Tories Spread Falsehoods in Canada

- – Continental Congress Resolutions Concerning Loyalists

- – Loyalists in Delaware and Maryland

- – A Loyalist Tract, 1781[?]

Teaching the Revolution, valuable overview essay by Prof. Carol Berkin, Baruch College (CUNY)

General Online Resources

1Catherine S. Crary, ed., The Price of Loyalty: Tory Writings from the Revolutionary Era (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1973), p. 4.

2 Ibid., p. 2.

Images:

– John Singleton Copley, oil portrait of Rev. Myles Cooper, ca. 1768 (detail). Columbia University; permission pending.

– "Liberty and No Tories," election proxy, Rhode Island, 1775 (detail). Reproduced by permission of the Rhode Island Historical Society. Digital image accessed through Early American Imprints Doc. 42930, American Antiquarian Society with Readex/NewsBank.

– A New Method of Macarony Making, as practised at Boston, colored aquatint, October 1774 (detail), National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, UK, PAF3919; reproduced by permission.

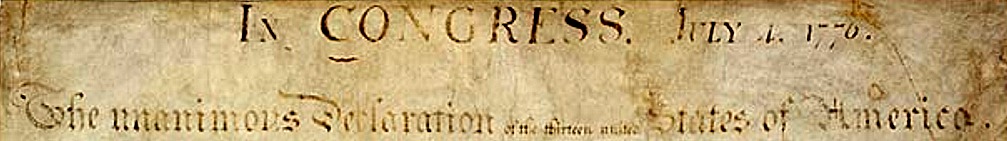

Banner image: Original Declaration of Independence, parchment, 1776 (detail); on exhibit in the Rotunda of the National Archives, Washington, DC. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

*PDF file - You will need software on your computer that allows you to read and print Portable Document Format (PDF) files, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you do not have this software, you may download it FREE from Adobe's Web site.