CONSTITUTION: 1787-1791

4. Opposing the Constitution

- Anti-Federalist letters to newspapers on the proposed Constitution, 1787-1788 PDF

- Anti-Federalist essays of "Philadelphiensis," 1787-1788, selections PDF

- Appeals for calm in the ratification debates, 1787-1788 PDF

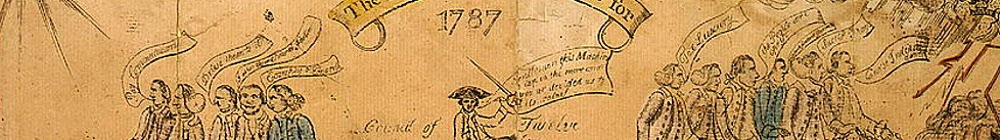

At right are details from an engraving entitled The Looking Glass for 1787 that satirized the contentious ratification debate in Connecticut. The state is represented as a wagon enmired in mud and weighted down with paper (heavy debt and inflated paper money), while two groups of state senators—supporters and opponents of the proposed Constitution—pull the wagon in opposite directions. The text balloons reveal their polarized contempt—"I abhor the antifederal Faction" and "curses on the Federal Govermt." As historian Jack Rakove reminds us, "the debate over ratification . . . took the form not of a Socratic dialogue or an academic symposium but of a cacophonous argument in which appeals to principle and common sense and close analyses of specific clauses accompanied wild predictions of the good and evil effects that ratification would bring."1 In the preceding section, Promoting the Constitution, we considered the Federalist voice in the "cacophonous argument"; here we sample the Anti-Federalist objections. To discern the variety of tone in the pieces—serious, sardonic, angry, humorous—read the pieces aloud. Follow the blend of impartial and impassioned rhetoric. How did these pieces function as persuasion and declamation?

Anti-Federalist letters to newspapers on the proposed Constitution, 1787-1788. Core readings for a study of the Constitution include the carefully reasoned essays written by the most accomplished political theorists of the day—including the Federalist Papers by Publius (James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay), and Anti-Federalist essays by Cato, Centinel, the Federal Farmer, the Columbian Patriot, and other Constitution critics.2 All these works first appeared in newspapers, and most were soon reprinted as pamphlets and books. Offering an intriguing companion to these essays are the shorter opinion pieces submitted by readers throughout the nation to their local newspapers. Eight short Anti-Federalist pieces are presented here from the peak months of national debate over the proposed Constitution. With a variety of genre and tone, they represent the major Anti-Federalist concerns about the proposed Constitution. What perspective do they add to a study of the ratification process? (6 pp.)

Anti-Federalist essays of "Philadelphiensis," 1787-1788, selections. Among the pseudonyms that abounded during the ratification debates, "Philadelphiensis" was adopted by a recent Irish immigrant working as a mathematics instructor at the University of Pennsylvania. His eleven fevered essays appeared over five months in two Philadelphia newspapers, during and after the state ratifying convention. Selections from six of his essays are presented here, including the sixth which was mercilessly satirized by Francis Hopkinson in his Federalist satire "The New Roof" (see the previous section, Promoting the Constitution). Workman condemned the proposed constitution as a device to consolidate power among the "well-born" elite and to relegate other citizens to the status of serfs and slaves, and he predicted British-like tyranny from the standing (permanent) national army that could be sent into the states to enforce federal law—both prevalent Anti-Federalist warnings. It is worthwhile to contrast the Philadelphiensis essays with the more reasoned and dispassionate works by Anti-Federalists like George Mason, Mercy Otis Warren, George Clinton, and others (see Supplemental Sites). (6 pp.)

Appeals for calm in the ratification debates, 1787-1788. Amidst the whirlwind of Federalist and Anti-Federalist essays, satires, poems, and letters that filled the newspapers during the ratification debates, occasionally a brief piece would appeal for calm, reason, and openness to the merits of an opponent's argument. "Cool heads are clear," wrote one letter writer; "turn your backs upon all fiery declaimers." Presented here are four such letters, followed by a dialogue between a Federalist and an Anti-Federalist that models civil discourse for antagonists whose "cool heads" had strayed. (4 pp.)

Discussion Questions

- Overall, what were the major Anti-Federalist objections to the proposed Constitution? Did they relate most to power, money, taxes, economic status, defense, slavery, voting, individual rights, or another factor?

- What did each side in the debate predict would happen to the new nation if the Constitution became the "supreme law of the land"?

- How did the authors portray their political opponents? To what did they ascribe the opposing positions?

- Compare these works with those in the previous section (#3: Promoting the Constitution). What styles of argument and rebuttal do you find in each? what forms of rhetoric and modes of persuasion?

- What are the plusses and minuses of using pseudonyms in political debate? Compare the practice in the 1780s with anonymous online commentary in the blogosphere today.

- How do the Constitution debates of 1787-1788 compare with citizens' political debates in the U.S. today? What lessons, tactics, etc., could each period take from the other?

- What primary issues and concerns prompted the short pieces? What local issues did they include?

- Compare the genres in the short Anti-Federalist pieces—allegory, poem, satire, opinion letter—with the political essay style of more well-known and nationally published Federalist and Anti-Federalist writings. What are the strengths of each genre? How did they suit their intended audiences?

- Study and evaluate the list of deficiencies in the Constitution that was submitted to a Massachusetts newspaper by "A Watchman." Which items are still relevant in 21st-century discussions of federal and state powers, representational fairness, taxation policy, and personal liberties?

- How do the short pieces expand your understanding of the ratification debates?

- What were Workman's main concerns about the proposed Constitution? Why did he present them as dire warnings?

- How did he respond to critics' dismissal of his warnings as "groundless conjectures"?

- In which arguments was he the most convincing, in your judgment? Why?

- Of what "schemes and collusions" did he accuse the Federalist supporters of the Constitution?

- What did he want his Federalist opponents to do to address the Anti-Federalist concerns?

- Compare Workman's essays with more dispassionate Anti-Federalist essays. What are the advantages and disadvantages of emotive persuasive writing in political debate?

- Write a dialogue between Benjamin Workman and his primary critic Francis Hopkinson. (Take note of their letter exchange in the Independent Gazetteer.) Perhaps include a third person, e.g., George Washington, the editor of the Gazetteer, a modern talk show host, or you. How will the dialogue conclude?

- Of the four appeals for calm and civil debate, which do you think would be most effective? Why?

- Which would you consider the least persuasive? Why?

- How did the dialogue entitled "The Federalist Anti-Federalist, returned to his Neighbors" model civil discourse in 1788?

- Write a similar dialogue for our times and issues. How will it resemble and differ from the 1788 model?

Framing Questions

- How did Americans' concept of self-governance change from 1776 to 1789? Why?

- How did their emerging national identity affect this process?

- What divisions of political ideology coalesced in this process?

- How did the process lead to the final Constitution and Bill of Rights?

- How do the Constitution and the Bill of Rights reflect the ideals of the American Revolution?

Printing

Anti-Federalist letters to newspapersAnti-Federalist essays of Philadelphiensis

Appeals for calm in the ratification debates

TOTAL

6 pp.

6 pp.

4 pp.

16 pp.

Supplemental Sites

- – Philadelphiensis essays:

- – I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX XI XII [no published essay X]

- – Major Anti-Federalist essays, 1787-88

- – Anti-Federalist letters and other documents

- – George Mason, Objections to the Constitution, 1787

- – Elbridge Gerry (Anti-Federalist), Statement to the Massachusetts legislature, 1787

- – The Federalist Papers, 1787-88

- – Other Federalist documents

Anti-Federalist letter from the "Yeomanry of Massachusetts," The Massachusetts Gazette, 25 January 1788 (History Matters)

Pseudonyms used in the U.S. Constitution debate (Wikipedia)

The Looking Glass for 1787, cartoon on the Connecticut ratification debates, 1787 Proceedings of the Massachusetts State Ratifying Convention, Elliott's Debates, Vol. II (Library of Congress)

Creating the U.S. Constitution (Library of Congress)

The Federalist Papers, 1787-1788 (Library of Congress)

Pamphlets (15) on the Constitution of the United States, Published during Its Discussion by the People, 1787-1788, ed. Paul Leicester Ford, 1888 (Online Library of Liberty)

"Was the American Revolution Inevitable?," not-to-miss teachable essay by Prof. Francis D. Cogliano, University of Edinburgh (BBC)

Teaching the Revolution, valuable overview essay by Prof. Carol Berkin, Baruch College (CUNY)

General Online Resources

1Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Knopf, 1996), p. 132.

2 Cato: Gov. George Clinton of New York. Centinel: Samuel Bryan of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania. The Federal Farmer: Melancton Smith of New York or Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. The Columbian Patriot: Mercy Otis Warren of Boston, Massachusetts.

Banner and slideshow images: details from The Looking Glass for 1787, cartoon on the Connecticut ratification debates, probably by Amos Doolittle, 1787. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC4-1722.

*PDF file - You will need software on your computer that allows you to read and print Portable Document Format (PDF) files, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you do not have this software, you may download it FREE from Adobe's Web site.