Lesson sponsored by ![]()

Advisor: John F. Kasson, Professor of History and American Studies,

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; National Humanities Center Fellow

©2013 National Humanities Center

Lesson Contents

How did the instant celebrity of Charles Lindbergh after his 1927 transatlantic flight reflect Americans’ values in the Twenties?

Understanding

Lindbergh’s daring flight — and his modest response to global fame — reassured Americans that their nation’s traditional values remained strong despite the tumultuous changes of the Roaring Twenties that were reflected in wild youth, rampant consumerism, celebrity worship, and political corruption.

Texts

- Fitzhugh Green on “the Phenomenon of Lindbergh,” essay entitled “A Little of What the World Thought of Lindbergh,” appendix in Charles Lindbergh’s We (1927), excerpts

- Optional introductory videos

- Newsreels, 1927: “Lindbergh Home” (1:22) and “America’s National Hero” (0.57)

- Animated cartoon: Disney Studios, Plane Crazy (Mickey Mouse), 1928 (6:00: view first 60 seconds)

Find more primary resources and discussion questions on the Twenties in the primary source collection Becoming Modern: America in the 1920s.

Text Type

Informational text with a clearly stated purpose and moderately complex structure, language features, and knowledge demands.

Text Complexity

Grades 9 and 10 complexity band.

For more information on text complexity see these resources from achievethecore.org.

Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups (full list at bottom of page).Tier 3 words are explained in brackets.

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.1 (Cite strong and through text evidence to support analysis…)

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.4 (Determine the meaning of words and phrases…)

Advanced Placement US History

- Key Concept 7.2 (ID) (…cultural and political controversies emerged…)

Advanced Placement Language and Composition

- Reading nonfiction… to identify and explain an author’s use of rhetorical strategies and techniques.

Teacher’s Note

To introduce the text, ask students to review a recent headline-grabbing celebrity event. What made the person a celebrity? What made the event a celebrity event? How was it covered in the media? How long did it receive media focus? How did the celebrity respond to the attention?

Review Lindbergh’s flight of May 1927 and the overwhelming receptions that welcomed him in Europe and the United States. Remind students that distressing news had dominated the headlines in the weeks before his flight — French pilots lost over the Atlantic, school bombing victims in Michigan, mine explosion deaths in Virginia, slain Marines in Nicaragua, desperate survivors of the Mississippi River floods, and the convictions of Ruth Snyder and Judd Gray for the grisly murder of Snyder’s husband. From the moment Lindbergh took off from California to fly to New York to commence his transatlantic attempt, the public followed his progress in 24/7 fervor.

To experience a bit of this fervor, and to begin visualizing the “phenomenon of Lindbergh,” view and discuss these brief online videos.

- Silent newsreels by British Pathé News (1927)

- “Lindbergh Home” (1:22): Lindbergh’s harbor welcome and ticker-tape parade in New York City.

- “America’s National Hero” (0.57): conclusion in Philadelphia of Lindbergh’s three-month “aerial tour of every state.”

- Plane Crazy (1928), animated cartoon by Disney Studios in which Mickey Mouse models himself after his hero Lindbergh and takes Minnie on a wild plane ride. (Focus on the first sixty seconds.)

Ask students to discuss what is meant by the word phenomenon in the phrase “the phenomenon of,” e.g., of a famous person, cultural fad, social innovation, political icon, etc. What is signified by the phrase? What makes a celebrity, trend, invention, etc., worthy of the heightened category “phenomenon”?

As the students begin the essay, have them skim for superlatives (greatest torrent of mass emotion, greatest welcome any man in history has ever received) and for adjective-noun phrases that describe Lindbergh (dauntless fellow, American boy, genuine exemplar). What immediate sense of the “phenomenon of Lindbergh” do students gain from this exercise? How do the illustrations in the text convey the unique and pervasive quality of the “phenomenon of Lindbergh”? (The illustrations were not published with Green’s essay in We.)

The follow-up assignment expands this lesson but could be used as a summative exercise for a unit on the 1920s. It asks students to analyze the description of Lindbergh’s arrival in Paris by his biographer A. Scott Berg. The piece situates Lindbergh’s achievement among broad international cultural and technological developments of the Twenties. It illustrates how the communications revolution of the period — the spread of radio and the establishment of newspaper syndicates, for example — spread his fame. It reflects the rise of advertising, the popularity of spectator sports, and the newfound prominence of the car. Moreover, it captures the party spirit and youthfulness of the time along with its urbanism.

Background

Contextualizing Questions

- What kind of text are we dealing with?

- When was it written?

- Who wrote it?

- For what audience was it intended?

- For what purpose was it written?

In the 1920s, an age of celebrity sensations and instant heroes, the fame of Charles Lindbergh was unique. His self-effacing response to public adulation — his modest presence amid cheering throngs — became celebrated in itself. He resisted offers for self-promotion and profit, shared credit for his achievement, and modeled what many championed as the true American character. By exhibiting lone courage and earnest humility, Lindbergh gave his countrymen a reassurance they craved — that the nation’s traditional values stood uncorrupted in the youth-obsessed and consumer-driven Twenties. To the elders who worried about the frivolousness and moral corruption of the young, Lindbergh was precisely what they thought a twenty-five-year-old should be — humble, virtuous, serious, and self-reliant. To the small town residents who resented the put-downs of urbanites, Lindbergh proved that solid rural values could triumph over big-city sophistication.

The text we analyze here appeared as an appendix in Lindbergh’s memoir We, which appeared two months after his flight. When its publisher wanted to include Lindbergh’s impressions of his instant global fame, Lindbergh assigned the task to his aide, the writer and naval officer Fitzhugh Green, who had accompanied him on his celebratory tours in Europe and America through mid June 1927. “Whatever the reason for it all,” wrote Green, “the fact remains that there was a definite ‘phenomenon of Lindbergh’ quite the like of which the world had never seen.” Defining and dramatizing this phenomenon would be Green’s goal in his essay. (Read the entirety of Green’s essay in We.)

Text Analysis

Excerpt 1

Close Reading Questions

1. Why did Green begin his essay with four short paragraphs listing the honors awaiting the first man to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean? Why didn’t he combine them in one paragraph?

Greene wants his readers to focus on each of the discrete elements in the first man over’s welcome home. This establishes a rhythm, which sets up the fifth paragraph. There he deflates the first man over and, in effect, wipes out all the honors bestowed on him, while imbuing the phrase “first man” with a forlorn irony.

2. Why did Green choose to write “make some money” instead of “make money”; “write several magazine articles” instead of “write magazine articles”; “be offered… jobs as manager of something or other” instead of “jobs in management”?

Presenting these achievements in such an off-hand style, Green suggests that they are the standard rewards that await the typical hero. They are expected, unremarkable and, as we see in the next paragraph, of little lasting value.

2. The first man to fly from New York to Paris was bound to be fêted and decorated. He would tell the story of his flight and there would be ephemeral discussion of its bearing on the future of aviation. Wild speculation about the world being on the brink of a great air age would follow.

3. The first man to fly from New York to Paris was bound to excite the admiration of his own countrymen. He would be met on his return by committees, have to make some speeches at banquets, and receive appropriate decorations for his valor.

4. The first man to fly from New York to Paris would write several magazine articles and a book. He might make some money by lecturing. He would be offered contracts for moving pictures, jobs as manager of something or other, and honorary memberships in a hundred organizations of more or less doubtful value.

It calls attention to his language and highlights the point Green is making about how unsentimental and abrupt the public can be in its fickleness. Celebrity quickly won can be quickly lost.

4. Why does Green write “the broad Atlantic” rather than simply “the Atlantic”?

In this paragraph Green contrast transatlantic flight with breaking a home run record and a murder. By describing the flight in grand terms — flying “the broad Atlantic” — he contrasts the magnitude of that achievement with the insignificance of the other two and again suggests just how fickle and frivolous public taste can be.

5. What is the function of paragraph six?

It illustrates the point Green made in paragraph five.

6. Who, by the way, can name the dauntless pilots that circled the globe by air not so many months ago?

He means that Lindbergh’s celebrity did not depend on his flight but rather stemmed from “the man” himself, qualities of his character and personality. Green here implies that Lindbergh’s celebrity is different from that of other heroes of the Twenties in that its sources run deeper than a mere one-time triumph.

8. The phenomenon of Lindbergh took its start with his flight across the ocean, but in its entirety it was almost as distinct from that flight as though he had never flown at all.

9. It is probable that in the three ensuing weeks Lindbergh loosed the greatest torrent of mass emotion ever witnessed in human history.

He intends simply to document the phenomenon of Lindbergh’s celebrity, not analyze it or explain its origins.

8. What speculation does Green offer to account for the phenomenon of Lindbergh?

He suggests four possible sources of Lindbergh’s appeal to the public: his modesty, his looks, his refusal to capitalize upon his success, his status as a youthful exemplar of honor and decency. The second interactive exercise in this lesson explores the sources of Lindbergh’s appeal in greater detail.

Excerpt 2

Close Reading Questions

9. In the first four paragraphs of this article Green describes the welcome a standard hero of the day, a nameless “first man over,” would get upon returning home and in so doing asserts the uniqueness of Lindbergh’s fame. In the two paragraphs analyzed in this section of the lesson he compares him to actual heroes. Why?

Again, he does so to illustrate how unprecedented Lindbergh’s fame is.

10. To compare Lindbergh with “past homecoming heroes,” why does Green contrast a hitching post with a green bay tree? How apt is the analogy?

Green uses this analogy to differentiate Lindbergh from earlier heroes. They were like “hitching posts” — well-worn and stable. In an apt comparison, Lindbergh, on the other hand, is like “a green bay tree,” young and still growing. Students who know their Bible might recognize the reference to Psalm 37:35 in which a “green bay tree” refers to a young tree flourishing in the soil of its native land.

11. Read aloud the first two sentences of paragraph two. How does the drumbeat list of names and adjectives — “Napoleon grim; Paul Jones defiant” — lead to the blunt finale: Lindbergh was none of these?

The first sentence sets up a rhythm that is abruptly broken with the short declarative sentence “Lindbergh was none of these.” This pattern focuses the reader’s attention on Green’s point, the historical uniqueness of Lindbergh’s heroism.

12. What contrasts does Green draw in paragraph two?

He contrasts the “everyday man” with the presidents, dictators, and military heroes of the past. And he contrasts their dramatic responses to fame — “glum,” “grim,” “defiant,” “blunt,” etc. — with Lindbergh’s pleasure, mild surprise, health, good spirit, and calm. In other words, in the midst of the wild acclaim accorded him, he remained a “normal” person.

13. How would you define the “phenomenon of Lindbergh”?

The “phenomenon of Lindbergh” refers to the unique quality of his celebrity. It was different from other instances of fame in four ways. First, it was unlike contemporary celebrity in the 1920s in that it was not supplanted by some triviality that wrenched public attention away from it. Second, it did not rely on a dramatic one-time triumph but rather on more enduring qualities of character and personality. Third, it was unprecedented in its exuberant emotion. Fourth, it differed from historical instances of fame in that it was visited upon a common man, and a young one at that, rather than an older, more venerable figure like a president or a general.

Note: Julius Caesar returned to Rome in 49 B.C.E. after conquering Gaul [France]; Napoleon to Paris in 1815 after escaping exile in Elba; Capt. John Paul Jones to the U.S. from Europe in 1781 during the American Revolution; Commander Robert Peary to the U.S. in 1909 after his Arctic expedition; Col. Theodore Roosevelt to the U.S. from Cuba in 1898 after the Spanish-American War; Adm. George Dewey to the U.S. from the Philippines in 1899 after the Spanish-American War; Pres. Woodrow Wilson to the U.S. from France in 1919 after World War I treaty negotiations; Gen. John J. Pershing to the U.S. from France in 1919 after World War I.

2. Caesar was glum when he came back from Gaul; Napoleon grim; Paul Jones defiant; Peary blunt; Roosevelt abrupt; Dewey deferential; Wilson brooding; Pershing imposing. Lindbergh was none of these. He was a plain citizen dressed in the garments of an everyday man. He looked thoroughly pleased, just a little surprised, and about as full of health and spirits as any normal man of his age should be. If there was any wild emotion or bewilderment in the occasion, it lay in the welcoming crowds and not in the air pilot they were saluting.

Follow-Up Assignment

How is the “phenomenon of Lindbergh” exhibited in these newspaper selections published during Lindbergh’s homecoming tour? The selections are from three big city general circulation newspapers, two African American newspapers, a Midwest agrarian newspaper, and a business/finance journal.

Distribute the seven excerpts among student groups to analyze, using the questions below. Groups may present their analyses for class discussion.

- How is the “phenomenon of Lindbergh” displayed in the selection? That is, how does the writer exhibit the “phenomenon” even if he/she doesn’t restate or evaluate it?

- Does the writer present a different perspective on the “phenomenon of Lindbergh,” e.g., a different message, emphasis, or consequence? If so, summarize the writer’s perspective. Why did he or she find it important to offer the different perspective?

Finally, have students write brief essays explaining the “phenomenon of Lindbergh” for a modern audience, referring to Green’s essay and the newspaper selections. How did the young Charles Lindbergh assure the nation of its values and strengths in the Twenties?

Vocabulary Pop-ups

- audacious: bold, daring

- fêted: celebrated; honored with parades, dinners, etc.

- ephemeral: short-lived

- dauntless: fearless

- ensuing: following

- torrent: flood, outburst

- composite: combination; a mixture of several elements

- deferential: respectful, dutiful

- imposing: commanding, striking

Images:

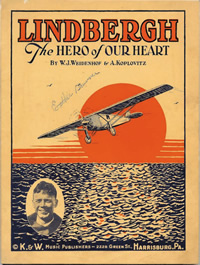

- Sheet music cover, “Lindbergh: The Hero of Our Heart,” song by W. J. Weidenhof and A. Koplovitz, 1927. National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution; Inventory No. D20040304043; SI-84-14740. Reproduced by permission.

- “San Diego Welcomes ‘Lindy,’ Sep’t. 21st, 1927,” commemorative postcard by Passmore Photo, 1927. San Diego Air and Space Museum. Reproduced by permission.