Advisor: Timothy H. Breen, William Smith Mason Professor of American History, Northwestern University, National Humanities Center Fellow

Copyright National Humanities Center, 2015

Lesson Contents

How did the aftermath of Shays’ Rebellion reflect the republican nature of the American government, especially the right to vote?

Understanding

Shays’ Rebellion (1786–1787) and its aftermath reflected more than just problems within the Articles of Confederation government. Reaction to Massachusetts’ treatment of the rebels following the insurrection served as a reminder to those in power of the republican nature of the American government. It emphasized the importance of the right to vote as a key element of the reciprocal duties between the government and its citizens.

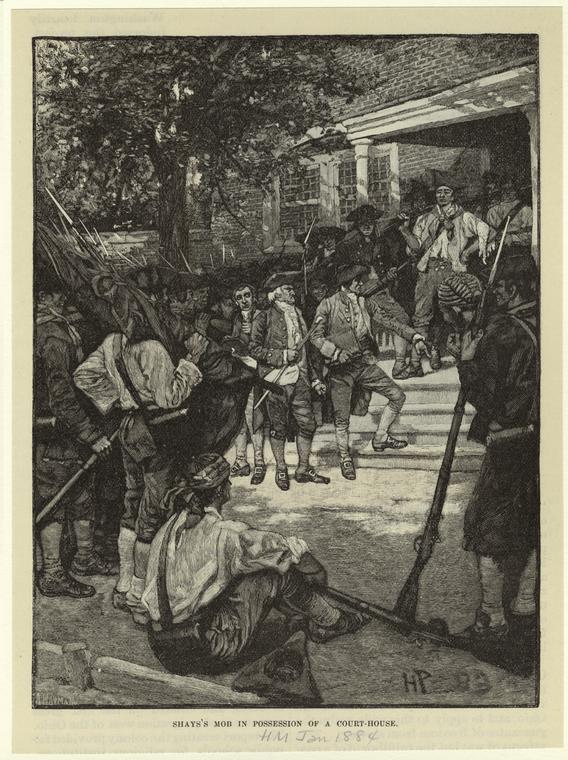

“Shays’s mob in possession of a court-house”

Text

Letter from General Benjamin Lincoln to General George Washington, 1787.

Find more correspondence at Founders Online from the National Archives.

Text Type

Letter, non-fiction.

Text Complexity

Grade 11-CCR complexity band.

For more information on text complexity see these resources from achievethecore.org.

In the Text Analysis section, Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups, and Tier 3 words are explained in brackets.

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.1 (cite evidence to analyze specifically and by inference)

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.6 (determine author’s point of view)

Advanced Placement US History

- 3.3 (IB) (frontier cultures… continued to grow, fueling… tensions)

Teacher’s Note

In this lesson students will analyze sections of a letter about Shays’ Rebellion written in 1787 by General Benjamin Lincoln (1733–1810) to General George Washington while the United States was still governed by the Articles of Confederation. Although George Washington had retired from public service in 1783, he remained concerned about the new nation he had helped create. News of the insurrection in Massachusetts as well as rumors of British support of Shays reached Washington. He sought reliable information and depended on friends from the Revolutionary days, especially Generals Henry Knox and Benjamin Lincoln, to keep him informed. While both men wrote to Washington regarding the Rebellion, this lesson uses the Lincoln letter only.

General Lincoln commanded the Massachusetts state troops that brought Shays’ Rebellion to a close, and he sent Washington a detailed letter after the Rebellion ended. While earlier sections of the letter describe military action, this lesson uses a section that focuses on the aftermath of Shays’ Rebellion and especially the punishment of the rebels. Lincoln states that Massachusetts’ decision to strip the rebels of the rights of citizenship, especially the franchise, did not reflect republican principles and would only make matters worse. In other correspondence, Henry Knox, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson all agreed that disenfranchisement was inappropriately harsh.

While historians debate the causes of Shays’, ranging from economic hardship to cultural clash to evolving legal policies, this lesson emphasizes instead the Rebellion’s aftermath, focusing on the value of voting rights (albeit only for white male landholders). Students have an opportunity to consider a number of questions regarding the relationship between a government and its citizens. Under what conditions should a citizen lose the right to vote? What are appropriate levels of response against a government that citizens feel is inattentive to their needs? What is the importance of including all eligible voters in the electorate? If a citizen cannot vote against an unsatisfactory office holder, what level of protest is appropriate?

Each of the four selections from the letter is accompanied by close reading questions. In excerpt one Lincoln explores his thoughts on the responsibilities of government in times of popular unrest, and in excerpt two he explains the critical importance of justice tempered with mercy. In excerpt three he investigates why denying the former rebels the right to vote is not in the government’s best interests, and in the final excerpt Lincoln puts forth reasons why they should retain the franchise.

Original spellings have been retained. While some resources spell Shays’ as Shays’s, in this lesson we use the more modern spelling. The lesson includes interactive exercises to help students understand vocabulary in context and review the text, and an optional follow-up assignment encourages students to explore the issue of compulsory voting. This lesson is divided into two parts, both accessible below. The teacher’s guide includes a background note, the text analysis with responses to the close reading questions, access to the interactive exercises, and a follow-up assignment. The student’s version, an interactive worksheet that can be e-mailed, contains all of the above except the responses to the close reading questions and the follow-up assignment.

Teacher’s Guide (continues below)

|

Student Version (click to open)

|

Background

Background Questions

- What kind of text are we dealing with?

- When was it written?

- Who wrote it?

- For what audience was it intended?

- For what purpose was it written?

In 1786 the United States was only three years old, and the economies of the new states were in turmoil. Although many states were able to recover from the Depression of 1784, Massachusetts, whose state economy was based on maritime trade focused around her eastern ports, was especially hard hit. After the Revolution, Britain restricted trade with the US, and countries were skeptical about the strength of American paper currency. Foreign nations demanded economic exchange in hard currency (gold and silver coin), and the eastern merchants of Massachusetts scrambled to comply. In addition, Massachusetts charged high taxes, payable only in coin, to its citizens to help pay its large Revolutionary War debt. Farmers in central and western Massachusetts resisted, as many were in debt, having borrowed to purchase their farms. Since these farmers rarely saw coin, generally using barter for economic exchange, many lost their farms or faced jail time for failure to pay their taxes.

Under threat of foreclosures and debtor’s prison, farmers fought back through special meetings, protests, closing courts that were jailing debtors, and freeing prisoners already jailed for non-payment. The rebels called themselves Regulators, committed to regulating the excesses of the government, and to give the movement validity they used many of the same strategies the colonists had used against the British 13 years earlier. Daniel Shays (1747–1825), farmer and former Continental Army captain, rose as the leader of the rebels. The Shaysites (the name given to Shays’ followers) included veterans, landholders, officeholders, militiamen, and Moses Sash, a free African American who became one of Shays’ captains. Even though the Shaysites saw themselves as reformers representing the voice of the people and with a direct connection to the patriots of the Revolution, the Governor and others saw them as dangerous radicals, challenging the new and still fragile government.

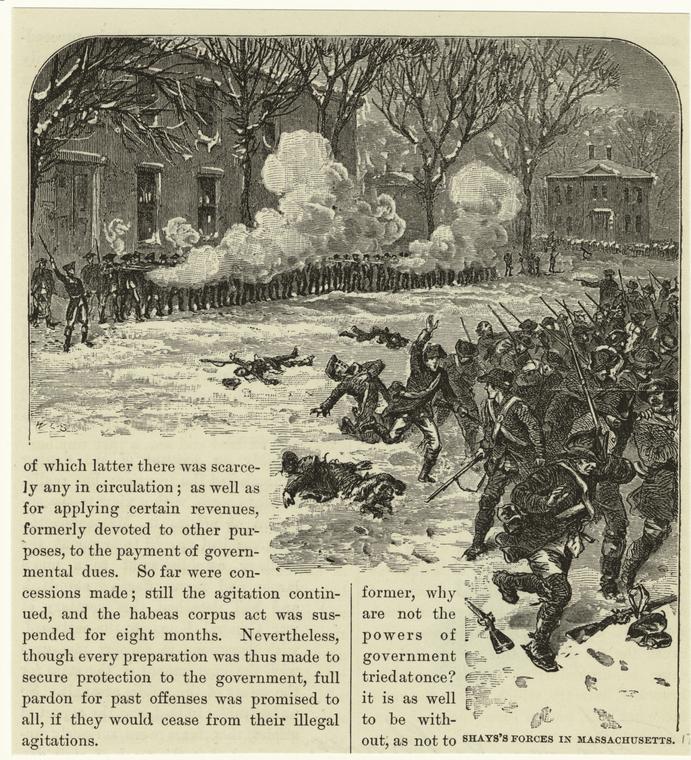

William Sheppard, “Shays’s forces in Massachusetts”

In this lesson General Lincoln comments on the punishment given to the rebels. He speaks of the Disqualification Act, passed by the Massachusetts Legislature in February, 1787, that outlined the conditions under which most men could obtain a pardon. Men were required to surrender their guns and take an oath of allegiance, at which time their names would be sent to the clerks in their home towns. They lost their rights of citizenship — they could not serve as jurors, become a member of the town or state government, or enter certain professions (school master, inn-keeper, or tavern keeper) for three years. They also lost the right to vote in town elections, and if they broke any of these rules, they would forfeit their pardons.

What happened to the Shaysites? Most of them were pardoned; eighteen men were condemned to hang, but only two were actually executed. Shays himself escaped to Vermont, was later pardoned, and died in New York in 1825. Governor Bowdoin was defeated in the election of 1787, and the new legislature cut taxes and stopped foreclosures. While Shays’ Rebellion never seriously threatened to overthrow the government of Massachusetts, in the context of the Annapolis Convention, which occurred during the Rebellion, and calls for the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 that were already in motion, it reminded political leaders of the importance of the relationship between citizens and their government.

In this passage, divided into four excerpts, you will hear General Lincoln speak of the role of government in times of unrest and argue that the strict punishments by Massachusetts — especially the loss of the right to vote — will have unintended negative consequences. In excerpt one Lincoln explores his thoughts on the responsibilities of government in times of popular unrest, and in excerpt two he explains the critical importance of justice tempered with mercy. In excerpt three he investigates why denying the former rebels the right to vote is not in the government’s best interests, and in the final excerpt Lincoln puts forth reasons why the former rebels should retain the franchise. While some resources spell Shays’ as Shays’s, in this lesson we use the more modern spelling. As you analyze the text, pay attention to Lincoln’s reasoning and why he believes that even the rebels should be allowed to vote.

Text Analysis

Excerpt 1

Close Reading Questions

Learn definitions by exploring how words are used in context.

1. Benjamin Lincoln begins this excerpt by describing current times. What has occurred in the recent past which has disturbed the community?

A rebellion has occurred which for a period of time was not contained. The Rebellion “stalked unmolested.”

2. Who was involved in this event? How closely did it affect individuals?

Neighbors turned against neighbors, even fathers and sons turned against each other.

3. In this type of uprising, what does Lincoln say the government may do?

He says the government may exert its powers and crush the rebellion.

4. According to Lincoln, the government has two responsibilities. What are they?

The government may crush the rebellion but it must also “reclaim its citizens, to bring them back fully to a sense of their duty”.

5. What branch of government is responsible to make sure that the rebels “embrace the Government with affection”?

The legislature is responsible — it will require “the wisdom, the patience & the address of the Legislature.”

6. What two bonds of civil society does Lincoln believe exist, and how do these bonds relate to each other?

Love and fear are the bonds. A successful government will rely on love first, and only use fear in emergencies.

7. Which of the two bonds is most desirable within a government? Why?

Love is “the noblest incentive to obedience a government supported here on is certainly the most desirable, and ensures the first degree of happiness…” Love makes the people happier.

8. When and how does Lincoln believe government should use fear?

The government should only use fear when “the general good renders it indispensable, and it will be removed the first moment it can be, consistently with the common safety.” Fear should only be used when absolutely necessary and should be withdrawn at the first possible moment.

When a State whose Constitution is like ours, has been convulsed by intestine broils; when the bands of Government have in any part of it been thrown off, and Rebellion has for a time stalked unmolested: when the most affectionate neighbours become in consequence hereof, divided in sentiment on the question in dispute, and warmly espouse the opinions they hold; when even the Father arms against the Son, and the son against the Father, the powers of Government may be exerted; and crush the Rebellion, but to reclaim its citizens, to bring them back fully to a sense of their duty, and to establish anew those principles, which lead them to embrace the Government with affection, must require the wisdom, the patience & the address of the Legislature.

Benjamin Lincoln, 1733–1810

Excerpt 2

Close Reading Questions

9. Why does Lincoln consider the period immediately after the Rebellion “the most critical”?

Lincoln sees the immediate post-rebellion period as “the most critical” because what happens at that time will determine the future relationship of the region’s citizens to the state government.

10. How does he describe appropriate punishment for the rebels?

He believes that punishment of the rebels must be severe enough to be a deterrent but moderate enough to be seen as fair, “that they [punishments] do not extend beyond a certain degree the necessity of which must be acknowledged by all.”

11. Why should the government show mercy to the rebels at this time?

Mercy must be applied to the rebels so that they respond in gratitude and “embrace with the highest cordiality” the government that was their enemy.

12. How will a governmental show of mercy affect individuals?

Governmental mercy will act as a model, encouraging neighbors and families to forgive each other and it will “be productive of the best Effects among contending Neighbours & divided Families.”

13. In the last paragraph of this excerpt Lincoln refers to a Massachusetts law that had recently denied the rebels their right to vote (The Disqualification Act, described in the Lesson Background). What is his opinion of this law?

He believes that the government might use the loss of the right to vote as a punishment, but it is being applied to too many people with this law. If the law had applied to fewer people, the area would have been just as safe, and it would have helped to promote the “general good.”

These are sentiments which I suppose have their foundation in truth; and in the belief of them, I have been led to examine with some attention the late Act of the General Court, by which certain Characters are for a time disfranchised. Although I think the conduct of the Legislature will make a rich page in History, yet I cannot but suppose, that if the number of the disfranchised had been less, the public peace would have been equally safe, and the general good promoted.

Excerpt 3

Close Reading Questions

14. What does Lincoln see as the results of The Disqualification Act in denying rebels the right to vote?

He believes that if the law is fully applied, entire towns may not be able to vote. He feels this would injure the entire state. “This will injure the whole, for multiplied disorders…”

15. Why did citizens protest against the government?

They had grievances that were not being met.

16. How did the government suggest that citizens deal with their complaints?

They should “seek redress in a Constitutional way, & wait the decision of the Legislature.”

17. If citizens are denied their right to vote as punishment for taking up arms, how will this prevent them from “seek(ing) redress in a Constitutional way”?

If they cannot vote, then they will not have a representative in the Legislature, and their grievances cannot be addressed by legislative means through their own representative.

18. How does Lincoln predict the rebels will respond as long as they are denied the vote?

He says they will not “submit to the terms” of the government except by fear “excited by a constant military armed force extended over them.”

19. How would this disfranchisement affect communities?

It would pit neighbor against neighbor and might even make some citizens leave the state. “There will be no affection existing among Inhabitants of the same Neighbourhood, or Families, where they have thought and acted differently…they will rather leave the State…”

The people who have been in Arms against Government and their Abettors, have complained, and do now complain that grievances do exist, and that they ought to have redress. We have invariably said to them, you are wrong in flying to Arms; you should seek redress in a Constitutional way, & wait the decision of the Legislature. These observations were undoubtedly just, but will they not now complain, and say, that we have cut them off from all hope of redress, from that quarter, for we have denied them a representation in that Legislative body, by whose Laws they must be governed.

While they are in this situation, they never will be reconciled to Government, nor will they submit to the terms of it, from any other Motive than fear excited by a constant military armed force extended over them. While these distinctions are made, the subjects of them will remain invidious, and there will be no affection existing among Inhabitants of the same Neighbourhood, or Families, where they have thought and acted differently. Those who have been opposers to Government will view with a jealous eye, those who have been supporters of it, and consider them as the cause which produced the disqualifying act, and who are now keeping it alive. Many never will submit to it, they will rather leave the State than do it. If we could reconcile ourselves to this loss, and on this account make no objection, yet these people will leave behind them near and dear connections who will feel themselves wounded through their Friends.

Excerpt 4

Close Reading Questions

20. Why does Lincoln believe “we have nothing to apprehend from them now, but their Individual Votes”?

He believes that the influence of the rebels has been broken, “fully checked.” Their influence now is only possible through their votes.

21. What does Lincoln believe should happen to the rebels? Why?

To those who obtain a pardon, they should be “at liberty to exercise all the rights of good Citizens.” (This would include the right to vote.) He feels that this is the only way they will live in peace under the government.

22. What does Lincoln believe may happen if the rebels are treated too strictly?

He believes they will “come forth hereafter with redoubled vigour”, and resist the government all the more.

23. From what group of citizens does Lincoln believe comes the most danger, even more than the rebels?

He believes that those citizens who are indifferent to government, and “inattentive to the exercise of those rights conveyed to them by the Constitution” are the most dangerous. They have no interest in the government and do not participate.

24. Describe the relationship Lincoln wants to see between citizens of a republic and their government.

Lincoln wants to see citizens who are loyal to the government out of affection and gratitude, who seek redress of grievances through legislative means, and who are actively engaged in the performance of their civic responsibilities, including that of voting. He wants to see a government that seeks to win allegiance and loyalty by arousing affection among its citizens, being restrained in its use of force, redressing grievances, and being willing to accommodate opposition viewpoints.

Review the central points of the textual analysis.

The influence of these people is so fully checked that we have nothing to apprehend from them now, but their Individual Votes. When this is the case, to express fears from that quarter is impolitic. Admit that some of these very people should obtain a seat in the Assembly the next year, we have nothing to fear from the measure: so far from that I think it would produce the most salutary Effects.

For my own part I wish, that those Insurgents who should secure a pardon, were at liberty to exercise all the rights of good Citizens; for I believe it to be the only way which can be adopted to make them good Members of Society, and to reconcile them to that Government under which we wish them to live. If we are now afraid of their weight and they are for a given time deprived of certain privileges, they will come forth hereafter with redoubled vigour. I think we have much more to fear from a certain supiness which has seized on a great proportion of our Citizens, who have been totally inattentive to the exercise of those rights conveyed to them by the Constitution of this Commonwealth. If the good people of the State will not exert themselves in the appointment of proper Characters for the Executive and Legislative branches of Government, no disfranchising acts will ever make us a happy & a well governed people.

Follow-Up Assignment: Compulsory Voting

In this letter Benjamin Lincoln states, “I think we have much more to fear from a certain supiness which has seized on a great proportion of our Citizens, who have been totally inattentive to the exercise of those rights conveyed to them by the Constitution of this Commonwealth.” He feels that the biggest threat to government comes from citizens who, through apathy or inattention, do not vote.

Some countries today require citizens to vote, including Belgium, Argentina, and Australia, although the sanctions for not voting vary widely. For instance, in Australia if you do not vote you must provide a reason why you did not vote or pay a $20 fine. Advocates of compulsory voting in the U.S. say it will increase voter turnout and citizen participation. The last time voter turnout for a presidential election in the U.S. was over 65% was in 1908, before women had the right to vote. Opponents of compulsory voting say it is not in accordance with the idea of free elections.

What do you think? Do you support the idea of compulsory voting in the U.S.? Research the issue and develop a response to agree with or challenge this statement: “Compulsory voting should be instituted in U.S. national elections.” Develop your argument with specific evidence to support your case. Present your completed argument to your classmates through a PowerPoint, Prezi, Animoto, or other method as determined by your teacher.

Vocabulary Pop-Ups

- convulsed: violently disturbed

- intestine broils: internal upheavals

- espouse: fully support

- indespensible: absolutely necessary

- deterred: prevented

- disposition: tendency

- delinquents: rebels

- beget: generate

- disfranchised: denied the vote

- rich: strong, vivid

- abettors: supporters

- redress: compensation

- reconciled: reunited

- invidious: envious

- checked: stopped

- apprehend: to fear

- impolitic: unwise

- salutary: beneficial

- insurgents: rebels

- redoubled: renewed

- supiness: passivity

- exert: make efforts

Text:

- “To George Washington from Benjamin Lincoln,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-04-02-0374-0002, ver. 2014-05-09). Source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 4, 2 April 1786 – 31 January 1787, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995, pp. 418–436.

Images:

- Pyle, Howard, & Hayman, A., Shays’s mob in possession of a court-house. 1884-01. From the New York State Education Department. Internet. Mid-Manhattan Picture Collection. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-f64e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed 19 November, 2014)

- Sheppard, William L., Shays’s forces in Massachusetts. 1882. From the New York State Education Department. Internet. Mid-Manhattan Picture Collection. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-f61f-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed November 19, 2014)

- Benjamin Lincoln, 1733-1810: Charles Willson Peale, from life, c. 1781–1783. Independence NHP. INDE 14097. http://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/revwar/image_gal/indeimg/lincoln.html (accessed March, 2015)