Advisor: Sylvia Chong, Associate Professor of American Studies, The University of Virginia

Lesson Contents

How did the Chinese in California confront anti-Chinese discrimination in the late 1800s?

Understanding

To confront rising intolerance in the 1870s, Chinese leaders in California appealed to local governments, Congress, and the President for fair treatment. In an 1873 appeal to the San Francisco city council, Chinese merchants offered a solution to the “Chinese question” that used thinly veiled irony to expose the pretense of Californians’ anti-Chinese demands. While the rallying cry of angry white workers was “the Chinese must go,” state leaders knew they should proclaim “the Chinese must stay,” because the state’s economy was dependent on the cheap labor provided by the Chinese immigrants. By using irony to confront the council with this fact, the leaders challenged them to acknowledge its truth and treat the Chinese justly.

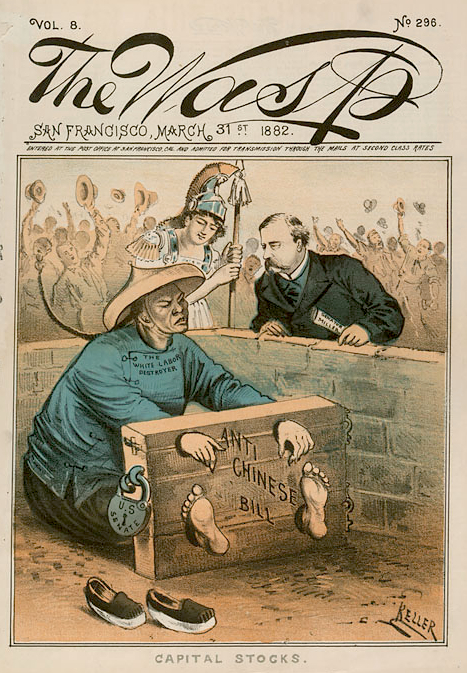

“Capital Stocks,” The Wasp, 1882

Text

The Chinese Question from a Chinese Standpoint, address to the San Francisco city council by Chinese merchants, June 2, 1873

[Find more primary resources on anti-Asian discrimination in The Gilded and the Gritty: America, 1870-1912 and Becoming Modern: America in the 1920s from the National Humanities Center.]

Text Type

Informational text; public address.

Text Complexity

Grades 11-CCR complexity band. (The short address with clear irony is also appropriate for grades 9-10.)

For more information on text complexity see these resources from achievethecore.org.

In the Text Analysis section, Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups, and Tier 3 words are explained in brackets.

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- ELA-Literacy.RI.11-12.6 (Determine and author’s point of view or purpose in a text in which rhetoric is particularly effective, and analyze how style contributes to the power and persuasiveness of the text.)

- ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.6 (Analyze point of view by distinguishing what is directly stated and what is really meant, e.g., irony and satire.)

Advanced Placement US History

- Key Concept 6.3 – I.B (Racist and nativist theories were used to justify national policies of discrimination and segregation.)

Advanced Placement English Language and Composition

- Reading nonfiction

- Satire and Irony

- Analyzing images

Teacher’s Note

In this lesson students will have the opportunity to study a compelling, carefully argued, witty call for justice. In 1873, alarmed by a growing Chinese population, the city council of San Francisco took several actions to encourage Chinese residents to leave the city and to discourage new immigrants from coming. In response a group of Chinese merchants appealed to the council for relief. Their address is the subject of this lesson. It is organized into six short sections, three of which (asterisked below) we examine in the Text Analysis section:

- Introductory Remarks*

- The Policy of China

- The Result of This Policy

- The Present Embarrassing Demands of America upon the Chinese Government

- Industrious*

- Our Proposition*

In their Introductory Remarks, the merchants establish a “calm, respectful” tone, reflecting the subservient attitude white Californians expected from the Chinese. Within this tone, they announce their intent to protest the “unjust,” “oppressive,” and “barbarous” actions of the council against the Chinese. In Sections Two through Four, they review the harm China has suffered from the influx of westerners forced upon it by western nations after China’s defeat in the “opium wars” of the mid-1800s. In the fifth section, Industrious, they review the benefits America has gained from Chinese immigrants, who are more law-abiding and industrious, the merchants suggest, than the European immigrants who are received “with open arms.” In the final section, Our Proposition, the merchants offer a proposal that not only confronts the council’s racism but also challenges America’s imperialist pretensions. The irony of their proposal indicates that by the end of their address they have moved well beyond their opening deference.

This lesson is divided into two parts, both accessible below. The teacher’s guide includes a background note, the text analysis with responses to the close reading questions, and a follow-up assignment. The student’s version, an interactive worksheet that can be e-mailed, contains all of the above except the responses to the close reading questions and the follow-up assignment.

Teacher’s Guide (continues below)

|

Student Version (click to open)

|

Background

Background Review Questions

- What kind of text are we dealing with?

- For what audience was it intended?

- For what purpose was it written?

- When was it written?

- What was going on at the time of its writing that might have influenced its composition?

With the opening of the American West, thousands of Chinese emigrated to the U.S. to take jobs building railroads, mining gold and silver, and clearing farmland. Most were poor rural men escaping economic turmoil in China, hoping to return to their families one day. Many answered the recruiting campaigns of American businesses that wanted cheap foreign labor. By 1870, 63,000 Chinese lived in the U.S. — most in California (50,000), comprising nine percent of the state’s population of 560,000. As their numbers grew, so did anti-immigrant hostility similar to the anti-Irish upheavals in the eastern U.S. Riots erupted in San Francisco in 1867 and Los Angeles in 1871, spurred by white laborers who resented the threat they perceived to their jobs and wages, especially after the economic downturn of the early 1870s. Politicians took up the anti-Chinese fervor in their campaigns and legislation, and newspapers stoked the fears of the “Chinese menace,” especially in San Francisco where one fifth of the state’s Chinese population lived. “The people of San Francisco have become thoroughly alarmed by the rapidly increasing influx of Chinese,” wrote one California newspaper, “and are using all the means within their power to rid the city of those already there, and to discourage the further immigration of this class…. They have been for years a curse upon this state.”*

In spring 1873, the city council of San Francisco took several actions to alienate the Chinese and drive them back to China:

- A resolution encouraging whites to stop hiring Chinese workers and to boycott Chinese goods and services. Such coordinated action would “throw the coolies upon their own resources” and open up jobs for the protesting white workingmen.

- An appeal to Congress to restrict the importation of Chinese labor. Without action, the council warned, “serious troubles will arise, and possibly bloodshed and disorder reign rampant… in organized efforts of the people to rid themselves of this Chinese plague.”

- A business tax on laundries that did not use animal-drawn vehicles to deliver laundry to their customers. This was aimed directly at the Chinese who delivered laundry on foot by suspending bags of clean laundry on long shoulder poles.

- A ban on removing human remains from city cemeteries without a permit. This was also aimed at the Chinese whose traditions called for sending their relatives’ remains to China for permanent burial.

- A requirement that city jailers cut prisoners’ hair to within one inch from the scalp. This would mean cutting the long queues (braided pigtails) of Chinese men — a move intended to dissuade them from choosing jail over a fine for violating the city’s tenement overcrowding laws (also considered a anti-Chinese move by critics). As one city paper noted, “to deprive a Chinaman of his queue is to humiliate him as deeply as possible.”

The mayor vetoed the “pigtail and laundry orders” and the cemetery proposal was tabled [action postponed]. One councilman expressed moral outrage at the enactments. But the anti-Chinese furor did not subside.

In this tense environment, leading Chinese merchants offered a proposal to the city council titled “The Chinese Question from a Chinese Standpoint.” Translated and presented by a sympathetic Methodist clergyman on June 2, 1873, it was published in the next day’s San Francisco Bulletin. Coverage of the “pigtail order” and the Chinese proposal appeared in national newspapers, including the top New York dailies. What made it so compelling?

In effect, the Chinese merchants offered a proposal that no one who profited from their labor could accept. The merchants’ “proposal” went like this: “You don’t like what we Chinese are doing here in America, and we Chinese don’t like what you Americans are doing in China. Easy solution. We all return to our native countries and everybody will be happy.” With this satiric proposal, the merchants confronted the council with the dire outcome of a “Chinese must go” policy: ”Is this what you really want?” Having established this framework, they make their actual request — treat the Chinese with fairness and dignity.

The New York Times hailed the address for its “delicate wit and subtle sarcasm [which] can hardly fail to be perceived, even by the average municipal [city] office-holder.” “Of course,” the Times concluded, “Americans will refuse to entertain [consider] this proposition, but will continue to insist upon their right to live and do business in China. How, then can they refuse to permit Chinamen to live and do business here, as, by treaty they have the express right to do?” (After its defeat by western nations in the Opium Wars of the mid-1800s, China had to agree to admit foreigners and to allow Chinese workers to emigrate to America.)

In 1874, the appeal was published as a pamphlet addressed “to the people of the United States of America.” This is the text presented here for your study. How did the Chinese leaders use irony, sarcasm, and satire — skillfully placed within their “calm respectful” proposal — to make their case for just treatment?

The aftermath: The mayor of San Francisco vetoed the “pigtail” and laundry orders. The council voted to override his vetoes, succeeding with the laundry order but not the “pigtail” order. The mayor then vetoed the second laundry order, saying it “savors of injustice to impose a heavier burden upon one class of laborers than is borne by others.” In 1880 the U.S. suspended Chinese immigration but agreed to protect the rights of current Chinese residents. Two years later Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, banning all Chinese immigration. The Chinese Exclusion Act was officially repealed in 1943, but not until 1965 were Chinese again admitted to the U.S. in large numbers. In 2012 Congress formally expressed regret for the Chinese Exclusion Act.

For more primary sources, see The Chinese in California: 1850-1925 from the Library of Congress, and The Chinese-American Experience, 1857-1892 from HarpWeek (Harper’s Weekly).

*See newspaper citations at the bottom of this page.

Text Analysis

Excerpt #1: Introduction

Close Reading Questions

1. In the merchants’ presentation to the council, they address the members as “Gentlemen.” Why was the salutation changed to “Brothers” in the published pamphlet?

The merchants announce from the outset that they are addressing the “people of the United States” as equals within the human race, not as inferior Chinese peasants begging for mercy.

2. Why do they begin with the question “Will you listen to a calm respectful statement?” instead of, perhaps, “We protest on behalf of the Chinese people”?

They place their appeal between two extremes: an obsequious plea and an insistent demand. They assert their respect for the council’s authority, implying that their remarks deserve respect in return. Also, by describing their remarks as “calm” and “respectful,” they contrast their appeal with the escalating anti-Chinese violence in California.

3. What is the “Chinese question” that the merchants propose to solve?

Whether the presence of the Chinese immigrants was a social and economic threat to the U.S., and therefore, whether they should be made to return to China. For many Americans, the presence of such an unfamiliar non-European immigrant group stirred elemental fears beyond competition for jobs and property.

4. In the first paragraph, how do they describe the anti-Chinese intolerance — with rage, sadness, or desperation?

They express an objective sadness at the vitriol aimed at them. To present themselves as reasonable men to the council, they would avoid the extremes of rage or desperation.

5. How does their tone change in the second paragraph?

They become more direct and assertive, declaring that the council’s enactments have “surpassed” the injustice of anti-Chinese laws outside San Francisco.

6. List the five adjectives with which the merchants describe the council’s anti-Chinese actions.

“Unjust, oppressive, barbarous, severe, discriminating.” Having established a tone of respect, the merchants are blunt in their appraisal of the council’s actions.

7. How do they soften the bluntness of these words?

By adding mollifying phrases like “what seems to us,” “if these enactments” and “you can hardly wonder,” the merchants keep their criticism from being a frontal assault on the council. “We might be wrong or too sensitive,” they imply, “but this is how it appears to us.” Of course the merchants don’t think they’re overstating their case. They are cautious to avoid angering the councilmen and losing their ear.

8. How do the merchants imply that the anti-Chinese laws violate American and Christian values?

The merchants state that if the laws are consistent with democracy and Christianity, then the Chinese are better off avoiding these aspects of American civilization. A zinger. The councilmen would know they are being called hypocrites in subtle language.

9. Why might they have avoided any mention of the specific enactments (e.g., the “pigtail” and laundry orders)?

They would want to avoid a contentious debate on the enactments themselves and, instead, aim their appeal at the overall goal of fair treatment.

10. How do the merchants add a self-effacing tone in the third paragraph? Do they mean it?

With phrases like “unfortunately for us,” “we must even now appeal,” and “who perhaps bear us no good will,” they appear to acknowledge the second-class status assigned them in white society. But the merchants are being intentionally sarcastic. By exaggerating the self-effacing tone, they reject the “kow-towing” stereotype of the Chinese peasant. [In the Chinese custom of the kowtow, one would show respect to the emperor by kneeling and bowing low to the ground.]

11. What message do they send by hailing the American press as “a mighty engine for molding public sentiment”?

“Our appeal will be heard far and wide.” The merchants know their address will be reported in the press, including national newspapers sympathetic to the Chinese (or opposed to anti-Chinese discrimination, at the least). The council knows this, too.

Brothers: Will you listen to a calm respectful statement of the Chinese question from a Chinese standpoint? Public sentiment is strongly against us. Many rise up to curse us. Few there are who seem willing, or who dare to utter a word in our defense or in defense of our treaty rights in this country. The daily papers teem with bitter invectives against us. All the evils and miseries of our people are constantly pictured in an exaggerated form to the public, and our presence in this country is held up as an evil, and only evil, and that continually. In California, Oregon, and Nevada, laws designed not to punish guilt and crime, nor yet to protect the lives and property of the innocent, have been enacted and executed discriminating against the Chinese; and the Board of Supervisors [city council] of the City of San Francisco, where the largest number of our people reside, has surpassed even these State authorities in efforts to afflict us by what seems to us most unjust, most oppressive, and most barbarous enactments. If these enactments are the legitimate offspring of the American civilization, and of the Jesus religion, you can hardly wonder if the Chinese people are somewhat slow to embrace the one or adopt the other.

Unfortunately for us, our civilization has not attained to the use of the daily press — that mighty engine for molding public sentiment in these lands — and we must even now appeal to the generosity of those, who perhaps bear us no good will, to give us a place in their [newspaper] columns to present our cause.

“Angel Island: the Ellis Island of the West,” 1917

Excerpt #2: Industrious

Throughout the address, they couch their blunt assessment of anti-Chinese intolerance in a polite nonthreatening tone, implying that anyone who would deny them a fair hearing is closed-minded.

13. When do they switch from “we wish” to “we protest”?

Only at the end of this section (the fifth of six) do they use the phrase “we protest,” placed climactically after a series of rhetorical questions (see below).

14. Specifically, what are they protesting?

They decry the “severe and discriminating enactments” of the city council, including the “pigtail,” laundry, and cemetery orders and other actions (see Background).

15. Why do they say they are protesting in the name of “our country,” justice, humanity, and Christianity?

They mean to elevate their protest to a moral appeal to human decency. It is not an ordinary request from residents to change a law or policy.

16. Why do they state that the Chinese in America do not run saloons or engage in “drunken brawls”?

They intend to favorably contrast the “industrious” Chinese immigrants with the Irish Catholic immigrants in the eastern U.S., who were stereotyped as ignorant heavy-drinking ne’er-do-wells. [Many white workingmen in California were Irish American, whose relatives had faced anti-Irish discrimination in the mid-1800s.]

17. Why do they repeat “your” when describing their contributions to America’s prosperity?

By repeating “your” as in “build your railroads” and “reclaim your swamp lands,” they emphasize the good they do for America instead of the harm America does to them (a point they make elsewhere). Many business ventures could not “exist on these shores” without their labor, they assert, implying that the appropriate response from Americans would be appreciation and just treatment.

18. The merchants then state their grievances as questions, not declarative sentences. Why is this effective here? (For example, they ask “Why these barbarous enactments?” instead of saying “We condemn these barbarous enactments.”)

These are “rhetorical questions,” in which the writer leaves a question unanswered, allowing the implied answer to form itself in the reader’s mind. In this way, the answer feels like the reader’s own response and not the writer’s opinion. For example, the reader is challenged to justify the “bitter hostility,” “barbarous enactments,” and “fearful opposition” toward the Chinese. The implied response is “such intolerance is unjustifiable.” On the other hand, a supporter of the “barbarous enactments” might call them “necessary protections.” By establishing the terms of debate, rhetorical questions can serve as powerful persuasive devices.

19. Write a rhetorical question to deliver the main point of paragraph four (“From Europe”).

Does it make sense to condemn the “industrious” and responsible Chinese when you welcome so many Europeans who are lazy, law-breaking, and contemptuous of American ideals?

20. Why do the merchants add “as we understand it” when referring to Christianity in the last paragraph?

As before, they suggest that American Christians are not abiding by the tenets of their religion when they act unjustly toward their fellow men. [In Section 3, they ask how Americans’ expectations of special treatment in China can be “reconciled to the ‘Golden Rule’” when one considers how unfairly Americans treat the Chinese in the U.S.]

21. When they appeal “in the name of OUR country,” do they mean China or America?

You could argue either way.

- “in the name of China.” Most Chinese immigrants hoped to return to China. They lived in Chinese enclaves (“Chinatowns”) and preserved their traditional culture, as did European immigrants in the eastern U.S. Appealing “in the name of China” would underscore their devotion to their homeland, a trait the council might respect in any group.

- “in the name of America.” In Section 3, they had noted the growing respect of the Chinese for American democracy and civilization. Also, by appealing “in the name of America,” the merchants allude to the U.S. refusal to extend citizenship rights to the Chinese as it did to European immigrants.

We wish now also to ask the American people to remember that the Chinese in this country have been for the most part peaceable and industrious. We have kept no whisky saloons and have had no drunken brawls resulting in manslaughter and murder. We have toiled patiently to build your railroads, to aid in harvesting your fruits and grain, and to reclaim your swamp lands. Our presence and labor on this coast we believe have made possible numerous manufacturing interests which, without us, could not exist on these shores. In the mining regions our people have been satisfied with [land] claims deserted by the white men. As a people we have the reputation, even here and now, of paying faithfully our rents, our taxes, and our debts.

In view of all these facts we are constrained [compelled] to ask why this bitter hostility against the few thousands of Chinese in America! Why these severe and barbarous enactments discriminating against us in favor of other nationalities?

From Europe you receive annually an immigration of 400,000 (among whom, judging from what we have observed, there are many — perhaps one third — who are vagabonds and scoundrels or plotters against your national and religious institutions). These, with all the evils they bring, you receive with open arms and at once give them the right of suffrage and not seldom elect them to office. Why then this fearful opposition to the immigration of 15,000 or 20,000 Chinamen yearly?

But if opposed to our coming still, in the name of our country, in the name of justice and humanity, in the name of Christianity (as we understand it), we protest against such severe and discriminating enactments against our people while living in this country under existing treaties.

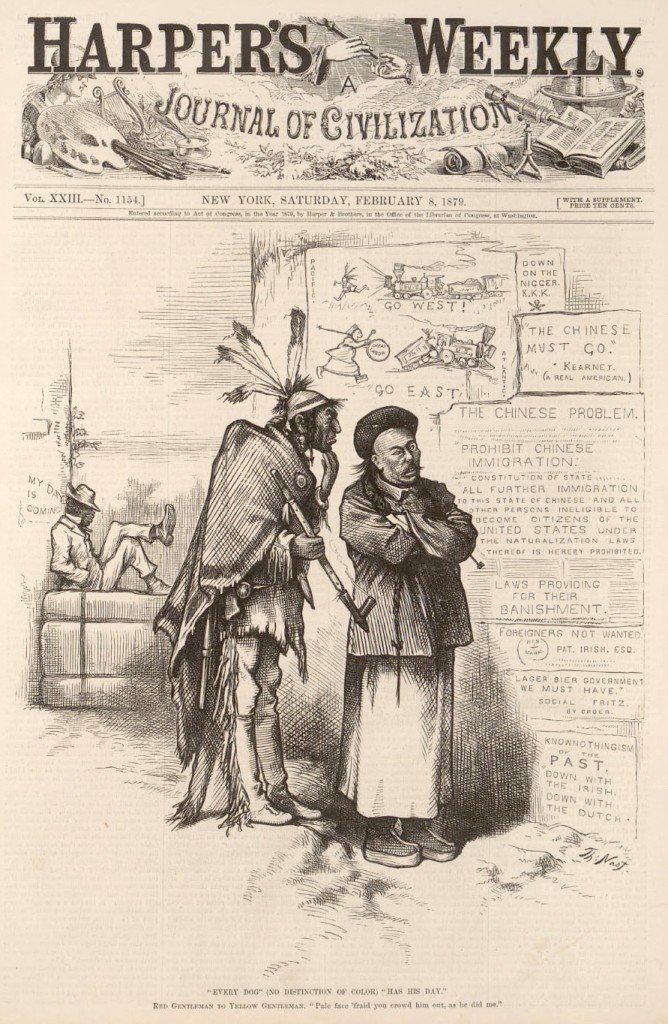

“Every Dog Has His Day,” Harper’s Weekly, 1879

Excerpt #3: Our Proposition

22. Irony is the difference between what is said and what is meant. What do the merchants say in their proposal, and what do they mean?

- What they say: “To solve the ‘Chinese problem’ that you say is harming America, let us end all relations between China and the U.S. All Chinese in America will return to China, and all Americans in China will return to the U.S. Everyone will be happy with the results.”

- What they mean: “If the Chinese leave the U.S., you lose the cheap labor supply you depend on. And if the Americans leave China, you lose the economic gains from Chinese trade. Both ways, the U.S. loses and China wins. China would welcome the end of your exploitative policies in China, and the Chinese in America would be glad to return home.”

23. Do Americans really want “all commercial intercourse and friendly relations [with China] to come to an end”?

No. The Chinese know it, and they know the councilmen know it, and the councilmen know that the Chinese know they know it, etc. This is often how irony works.

24. Sarcasm is language that conveys contempt or ridicule, often through witty or exaggerated language. How do the merchants use sarcasm at the end of their proposal?

They rhetorically “roll their eyes” at the charge that the Chinese pose an elemental threat to American civilization.

- In sentence one, they exaggerate the word “SO” to scorn the idea that the Chinese are “SO detrimental” and “SO offensive.” (Read the sentence aloud to hear the sarcasm.)

- In sentence three, they emphasize the “perhaps” and add “it is said” to ridicule the idea as absurd. Ending the sentence with an exclamation point implies “Can you believe anyone would think this way?”

- In the last paragraph, they say their proposal would deliver a “desirable state of affairs” for the Chinese — but not for the Americans. They describe the U.S.–China treaty, which the Chinese accepted in defeat, as “sacred,” implying that Americans should obey the treaty that they forced on the Chinese. They “humbly pray” for respect, a sarcastic allusion to the stereotype of the obsequious Chinese “coolie.”

25. Why do they ask for respect “in the meantime”?

They know the U.S. will not send the Chinese home. Thus there is no “meantime”; the Chinese are a permanent part of American society.

26. What is their ultimate request of the council, as stated in the last sentence?

They repeat their appeal for fair treatment as human beings, specifically that the U.S. abide by its 1868 treaty with China, in which it agreed to grant to Chinese immigrants the “same privileges, immunities, and exemptions in respect to travel or residence” as enjoyed by U.S. citizens.

27. If this was their ultimate request, why did they place it in the context of a satiric “proposal”?

- To get the council’s attention (and that of the press), their appeal would need to be unique in some way, to carry a punch.

- Through irony and sarcasm, they could deliver indirect messages to the council and the American people (“you’re being hypocritical,” “you know you need us to stay”) while directly protesting the specific actions of the council.

28. The New York Times hailed the address for its “delicate wit and subtle sarcasm [which] can hardly fail to be perceived.” How do you think the city council responded to the Chinese merchants’ proposal? [NYT, June 17, 1873]

Students may offer conjectures on the council’s response to the appeal, and on its influence in the national debate on Chinese immigration. (See Background, above, for the aftermath of the “Chinese question.”)

Finally, since our presence here is considered so detrimental to this country and is so offensive to the American people, we make this proposition, and promise on our part to use all our influence to carry it into effect. We propose a speedy and perfect abrogation and repeal of the present treaty relations between China and America, requiring the retirement [withdrawal] of all Chinese people and trade from these United States, and the withdrawing of all American people and trade and commercial intercourse whatever from China. This, perhaps, will give to the American people an opportunity of preserving for a longer time their civil and religious institutions which, it is said, the immigration of the Chinese is calculated to destroy!…

This is our proposition. Will the American people accept it? Will the newspapers, which have lately said so many things against us and against our residence in this country, will they now aid us in bringing about this, to us, desirable state of affairs? In the meantime, since we are now here under sacred treaty stipulations, we humbly pray that we may be treated according to those stipulations until such time as the treaty can be repealed and all commercial intercourse and friendly relations come to an end.

Signed in behalf of the Chinese in America, by

LAI YONG

A YUP

CHUNG LEONG

YANG KAY

LAI FOON

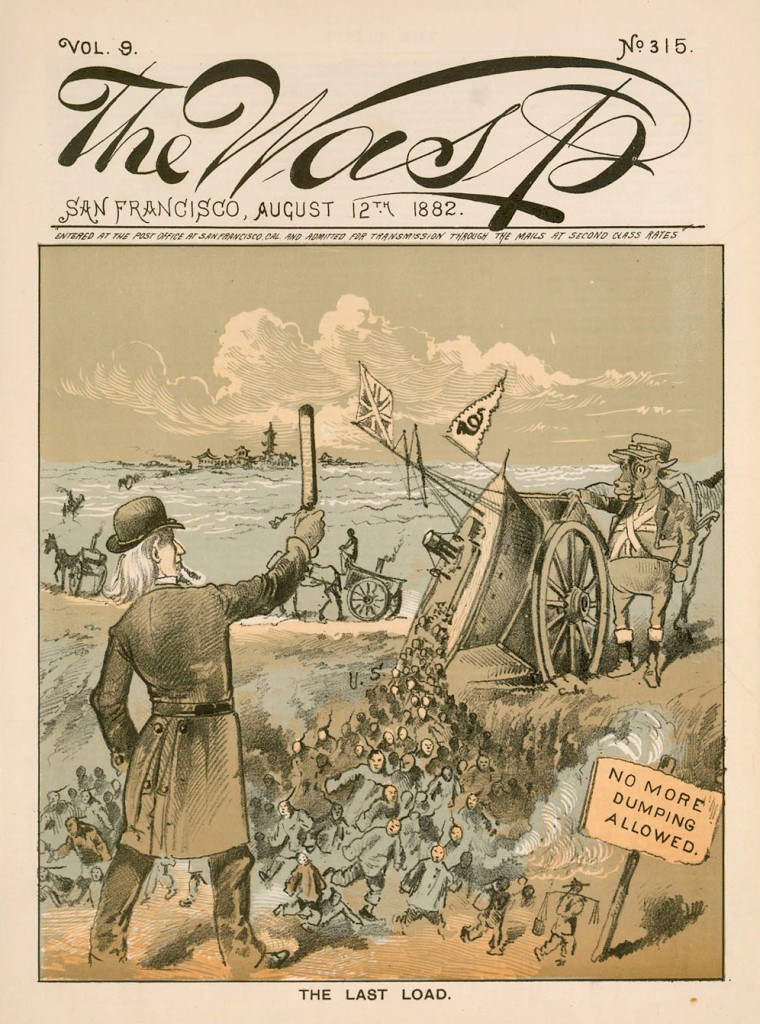

“The Last Load,” The Wasp, 1882

Follow-Up Assignment

Write a brief essay interpreting this cartoon — published in The Wasp, a San Francisco magazine — in 1878. Do you see it as pro-Chinese or anti-Chinese? Support your argument with evidence from the address of the Chinese merchants and from the cartoon itself. (Click image to enlarge.)

Write a brief essay interpreting this cartoon — published in The Wasp, a San Francisco magazine — in 1878. Do you see it as pro-Chinese or anti-Chinese? Support your argument with evidence from the address of the Chinese merchants and from the cartoon itself. (Click image to enlarge.)

Vocabulary Pop-Ups

- invective: insulting and abusive language

- vagabond: wanderer, tramp, vagrant

- suffrage: the right to vote

- detrimental: harmful

- abrogation: cancellation, annulment, repeal; turning against

Text: “The Chinese Question from a Chinese Standpoint,” pamphlet, 1874; Edward Lee Papers, Asian American Studies Collections, Ethnic Studies Library, University of California, Berkeley; reproduced by permission. See digital images of the pamphlet in American Memory, Library of Congress.

Newspaper articles accessed through America’s Historical Newspapers (NewsBank and the American Antiquarian Society).

- “Board of Supervisors. Regular Weekly Meeting…,” San Francisco Bulletin (published as the Daily Evening Bulletin), 1 May 1873.

- “The Chinese Puzzle: Proposed Local Legislation to Check Immigration from China,” SFB, 27 May 1873.

- “The Supervisors on Hair Cutting,” SFB, 2 June 1873.

- “John Chinaman Again,” SFB, 3 June 1873.

- “The Anti-Chinese Movement,” Mariposa [California] Gazette, 6 June 1873.

- “John Chinaman and the ‘Pig-Tail’ Order,” New York Tribune, 13 June 1873.

- “The Chinese Crusade,” The Elevator [San Francisco], 14 June 1873.

- “Lai Yong’s Letter,” The New York Times, 17 June 1873.

- “The Anti-Chinese Ordinances,” SFB, 24 June 1873.

- “Board of Supervisors. Regular Weekly Meeting…,” SFB, 1 July 1873.

Image credits:

- “Capital Stocks” The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, [call no. 296] http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/flipomatic/cic/images@ViewImage?img=brk00001510_16a as cited in http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/cic:@field(DOCID+@lit(brk1510))

- “Angel Island,” California Historical Society, San Francisco [call no. PAM1277] http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/flipomatic/cic/chs1104 as cited in http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/cic:@field(DOCID+@lit(chs1104))

- “Every Dog Has His Day,” The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley [call no. MTP/HW: Vol.23:101] http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/flipomatic/cic/images@ViewImage?img=brk00007045_16a cited in http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?cic:164:./temp/~ammem_iSEe:

- “The Last Load,” The Bancroft Library, University of Calfornia, Berkeley [call no. 315] http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/flipomatic/cic/images@ViewImage?img=brk00001532_16a as cited in http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?cic:264:./temp/~ammem_iSEe:

- “The Chinese Must Go! But, Who Keeps Them?”, The Wasp, 11 May 1878 (v. 2, Aug. 1877-July 1878). Collection: Chinese in California, Identifier: no. 93 pages 648-649.