How did scientific Progressivism, when applied to housekeeping, change homemaking

and the traditional concept of the homemaker?

Lesson Contents

Understanding

From the 1890s through the 1920s, Progressivism manifested itself in a variety of ways from cleaning up slums to eliminating government corruption to Americanizing immigrants to standardizing industrial practices. Such initiatives often sought to improve life by applying insights derived from the newly emerging social sciences—disciplines like sociology, psychology, economics, and statistics. When applied to housework, this scientific strand of Progressivism not only promoted efficiency in such tasks as washing dishes and cleaning but also encouraged women to think of themselves in a new way, not simply as homemakers but as professionals skilled in the science of home management.

Christine Frederick, ca. 1913

Text

Christine Frederick, The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management![]() , 1913 (excerpts).

, 1913 (excerpts).

Text Type

Informational text with a clear purpose, slightly complex structure, and moderately complex language features and knowledge demands. Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups (full list at bottom of page).

Text Complexity

Grades 6-8 complexity band.

For more information on text complexity see these resources from achievethecore.org.

In the Text Analysis section, Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups, and Tier 3 words are explained in brackets.

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.1 (Cite strong and through text evidence to support analysis…)

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.4 (Determine the meaning of words and phrases…)

Advanced Placement US History

- Key Concept 7.1 (II-A) (…progressive reformers…worked to reform existing social…institutions…)

Teacher’s Note

Typically, units on Progressivism focus on its broad initiatives: the urban settlement house movement, health regulation, government reform, trustbusting, muckraking, consumer protection, woman suffrage, etc. This lesson gives students the opportunity to study how the Progressive reformist impulse influenced American life in more intimate and unexpected ways.

One strain of Progressivism relied upon the insights of the social sciences, and that strain gave rise to scientific management, which sought to routinize manufacturing processes to achieve greater efficiency. Through the work of household advice guru Christine Frederick scientific management found its way into the middle class home, giving women not only new ways to clean and cook but also a new way of thinking of themselves.

This lesson analyzes brief excerpts from Frederick’s 1913 book The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management. The first excerpt, from chapter one, sets forth the definition of efficiency and explores its characteristics. It also focuses on the persona Frederick creates and traces the way that persona changes. The second excerpt, from chapter twelve, shows that Frederick was aiming at much more than a better way to do dishes. She identifies a problem that, according to her, confronts millions of women: a stultifying, mind-numbing malaise brought on by the ceaseless drudgery of housework, a condition that sounds remarkably like the affliction Betty Friedan identified fifty years later in The Feminine Mystique. Frederick asserts that efficiency will cure it, not so much because it will make housework easier but chiefly because it gives the mind something to do. The planning, experimentation, and research required to find the most efficient way to perform mundane chores, she argues, transforms housework into an intellectual pursuit. Viewed this way, cooking, washing, and cleaning cease being cooking, washing, and cleaning and become problem solving. The domestic work middle class housewives do at home comes to look like the administrative and managerial work their husbands do in the office or factory. In their own way they become “efficiency men” and, like those men, do “great and noble work.”

This lesson is divided into two parts, a teacher’s guide and a student version. The former includes a background note, an analysis of the text with responses to close reading questions, access to interactive exercises, and an optional follow-up assignment. The student version, a PDF that can be completed online or printed for distribution, includes all of the above except the answers to the close reading questions and the follow-up assignment. This lesson features two interactive exercises. The first allows students to explore vocabulary in context. The second challenges them to apply the principles of scientific management to the task of designing an efficient kitchen.

Background

Contextualizing Questions

- What kind of text are we dealing with?

- When was it written?

- Who wrote it?

- For what audience was it intended?

- For what purpose was it written?

Progressivism drew its inspiration from two sources-evangelical Protestantism and the sciences, both the natural and social sciences. In the early nineteenth century evangelical Protestants undertook reforms out of a desire to purge sin from a rural agricultural nation. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries they aimed their fervor at the vices of an urban industrial America. The reforming spirit of Protestantism inspired many who did not embrace the doctrines of Protestantism or its often dark and pessimistic world view. Among these were many social scientists, specialists in such disciplines as psychology, economics, sociology, and statistics. These scientific Progressives conducted experiments and gathered data in an effort to discover the underlying laws that governed human behavior. Armed with such knowledge and with faith in its uplifting and improving power, they optimistically believed they could devise solutions to problems ranging from labor unrest to unsanitary living conditions to inefficient manufacturing. Their interventions were generally characterized by a desire to control natural forces and impose a degree of order on them.

When applied to tasks performed with “the head and hands working in cooperation,” control and order were supposed to result in greater efficiency. In The Principles of Scientific Management (1910), one of the most influential books of the twentieth century, engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor described how to apply efficiency-promoting practices to large manufacturing operations. So powerful were his ideas that they quickly migrated to other areas of life, including the kitchens of middle-class housewives.

The person responsible for bringing scientific management to the home was Christine Frederick (1883-1970). Upon graduating from Northwestern University in 1906, she became a teacher, an acceptable occupation for a woman because it addressed the welfare of children and thus fell into what the age considered the domestic sphere. After a year in the classroom, she married J. George Frederick, a business executive, and began life as a homemaker in New York. In time she became bored with housework and sought another outlet for her energy. From her husband’s associates she learned about the new scientific management practices that were revolutionizing American industry. (See “Progressivism in the Factory” in America in Class® Lessons.) In 1912 she wrote a series of articles that showed the middle-class readers of Ladies’ Home Journal how to apply the new management techniques to the running of their homes. A year later she published the collected series under the title The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management, in which she offered women a great deal more than new ways to clean and cook. By transferring the principles of scientific management from the factory floor to the kitchen, Frederick not only brought the domestic sphere into the industrial system but also gave housewives a new way of thinking of themselves.

Text Analysis

From Chapter One: Efficiency and the New Housekeeping

Close Reading Questions

1. In her opening paragraph Frederick begins to establish a persona—a “character” who speaks directly to us. What do the details of the scene described here tell us about her persona?

They tell us that she is a married women and that she was, at least “a year ago” a traditional housewife doing her “mending.” The scene also suggests that she is of the middle class: her husband is a businessman, not a laborer; she has a library, which suggests a degree of affluence, but she is repairing old clothes, which suggests that she does not discard them as a wealthy woman might.

2. Why would Frederick want to establish the persona of a middle class housewife?

Because she is writing for an audience of middle class housewives. She is, in effect, saying, “I’m one of you. My life is like yours. You can trust what you read here.”

3. What does the fact that she stops to listen to her husband’s conversation suggest?

It suggests that she has a sense of curiosity that can take her beyond the domestic sphere.

4. What terms does Frederick introduce in paragraph 2?

“Efficiency,” “standard practice,” “scientific management.”

“Efficiency,” I heard our caller say a dozen times; “standard practice,” “motion study,” and “scientific management,” he repeated over and over again. The words suggested interesting things, and as I listened I grew absorbed and amazed.

“What are you men talking about?” I interrupted. “I can’t help being interested. Won’t you please tell me what ‘efficiency’ is, Mr. Watson? What were you saying about bricklaying?”

That it is

- a new idea from the world of

business and manufacturing, - synonymous with “scientific

management,” - the work of engineers,

- based on careful observation and study of motion and time,

- intended to enable workers to do more in less time,

- intended to improve working conditions, profits, and pay.

6. Based on what you learned in paragraph 4, write a definition of “efficiency.”

Answers will vary but should include, in one way or another, the key details listed above.

It suggests her intense interest in the topic, signaling to her readers that they should be interested, too. But it is not too farfetched to say that it is also a symbolic action, suggesting that with the arrival of scientific management in the home, the traditional conceptions of the housewife and housework will be set aside.

8. How does Frederick develop paragraph 6? What phrase indicates her method?

The phrase “for instance” indicates that she develops it through example.

9. What does paragraph 6 illustrate about scientific management?

It illustrates the method and purpose of scientific management. The abundance of numbers indicates the extent to which scientific management relies on careful observation and measurement, and the increase in the bricklayer’s output illustrates

its goal.

“Well, for instance,” answered Mr. Watson, “this is how they improved the method of laying bricks: Formerly a workman stood before a wall, and when he wanted to lay a brick he had to stoop, pick a brick weighing four and a half pounds from a mixed pile at his feet, and carry it to the wall. Suppose he weighed one hundred and eighty pounds; that worker would have to lower his one hundred and eighty pounds four feet every time he picked up each of the two thousand bricks he laid in a day! Now an efficiency expert, after watching bricklayers at work, devised a simple little table which holds the bricks in an orderly pile at the workman’s side. They are brought to him in orderly piles, proper side up. Because he doesn’t need to stoop or sort, the same man who formerly could lay only one hundred and twenty bricks an hour can now lay three hundred and fifty bricks, and he uses only five motions, where formerly it required eighteen.”

The tone is light, casual, even slightly flirtatious.

11. How does Frederick establish the tone of the paragraph?

The word “bantered” introduces connotations of lightness and casualness. “Smart men” and the italicized “we” introduce the slightly flirtatious note by flattering men, suggesting a distinction between their “great and noble” endeavors (See paragraph 11 below.) and the mundane work of housewives. Frederick emphasizes this distinction with the ironic suggestion that housewives could “save millions” by adopting scientific management.

12. After reading this paragraph, how would you describe the narrator?

While curious and skeptical about scientific management, she seems playful, light, not too serious.

“It does sound like magic,” Mr. Watson replied, “but it is only common sense. There is just one best way, one shortest way to perform any task involving work done with the hands, or the hands and head working in cooperation. These efficiency men merely study to find that one best and shortest way, and when they have found it they call that task ‘standardized.’ Very often the efficiency is increased because the task is done with fewer motions, with better tools, because of even such a simple thing as changing the height of a work-bench, or the position of the worker.” . . .

The language in paragraphs 1, 2, and 3 is questioning and polite; that of paragraph 7 is light and casual. In paragraphs 9 and 10 it is authoritative, confident, and assertive.

14. What accounts for this new tone in the narrator’s conversation with Mr. Watson?

The narrator is speaking from her own area of expertise.

15. After reading these paragraphs, how would describe the narrator?

She is still a housewife but no longer a naïve tyro or flirtatious questioner. This passageestablishes her as Mr. Watson’s intellectual equal and a fit guide to the intricacies of scientific management.

“Now, Mrs. Frederick,” replied Mr. Watson seriously, “that is really not too much to imagine. There is no older saying than ‘woman’s work is never done.’ If the principles of efficiency can be successfully carried out in every kind of shop, factory, and business, why couldn’t they be carried out equally well in the home?”

It equates housework with the “great and noble” things men are doing in the wider world and offers women a way to participate in them.

17. In paragraph 11 how does Frederick redefine the home, homemaking, and the homemaker?

She redefines homemaking as a quest for efficiency. She redefines the homemaker as a professional, a researcher, an efficiency engineer. The home then becomes an extension of the industrial system, akin to a factory or an office.

From Chapter Twelve: Developing the Homemaker’s Personal Efficiency

- up against it

- never-ending-ness, the detailed-ness, the wearing-ness of their work

- closes over women

- women confess themselves overcome,

- slave to master

work.

. . .

[T]here are literally millions of women in the world to-day who feel “up against it” about their households. They have helpful household magazines a-plenty, and labour-saving devices a-plenty, but the never-ending-ness, the detailed-ness, the wearing-ness of their work become too much for them. It closes over women like water over a drowning person, and women confess themselves overcome, actually assuming the mental attitude, in regard to their work, of slave to master, instead of master to slave.

The “first great work of efficiency” is to change women’s attitude toward housework.

20. How does efficiency in the home, as described in paragraph 15, bring about a change in attitude?

Concentrating on efficiency stimulates the mind and overcomes the tedium—“the neverending-ness, the detailed-ness, the wearing-ness”—that housework inflicts. The efficient attitude of mind replaces the feeling of helpless oppression with “hope, zest, and cheer.” Efficiency itself gives housewives a tool with which to overcome the daunting challenges of homemaking and breeds a sense of confidence, making them masters in their homes rather than slaves.

21. How does the “efficient attitude of mind” redefine housework?

It transforms housework into an essentially intellectual undertaking, an exercise in continuous problem-solving.

The woman who interests herself deeply in the smallest detail and new angle or idea about her work is preparing . . . to act intelligently and successfully under trial and difficulty. . . . [T]he efficient housewife loves to tackle anything that confronts her with her trained, efficient attitude of mind, taking hope, zest, and cheer in her job, and using all the knowledge, help, and suggestion from anywhere that promise to prove useful.

Follow-Up Assignment

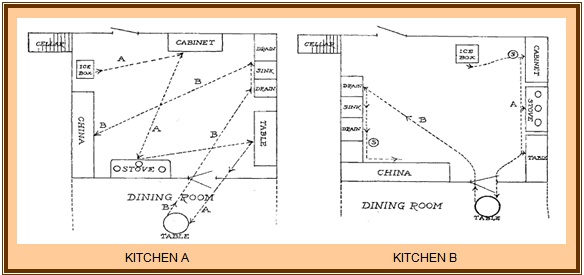

Examine the diagram below, which comes from The New Housekeeping. Based on your analysis of the excerpt above, determine which kitchen arrangement Frederick would endorse and write a paragraph explaining your choice. Cite specific details from the diagram and evidence from the text to support your conclusion.

- skeptically: questioningly, doubtingly

- bantered: joked, quipped

Images:

– Photograph captioned “Mrs. Christine Frederick at the preparing table in the kitchen of the Applecroft Experiment Station, Greenlawn, Long Island,” ca. 1913 (detail), frontispiece of Christine Frederick, The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management, 1913. Digital image courtesy of Google Books.

– Illustrations titled “Diagram Showing Badly Arranged Equipment” and “Diagram Showing Proper Arrangement of Equipment,”in Frederick, The New Housekeeping, 1913, p. 52 of 1918 edition. Courtesy of Google Books.