Advisor: Timothy H. Breen, William Smith Mason Professor of American History, Northwestern University, National Humanities Center Fellow.Copyright National Humanities Center, 2011

Lesson Contents

How did the Battles of Lexington and Concord change the character of American resistance to British rule?

Understanding

From the early 1760s to 1775 American colonists complained bitterly about British policies that taxed them without representation. Nonetheless, they did not advocate taking up arms against king and parliament. The Battles of Lexington and Concord changed that. The killing of Americans by British troops altered popular perceptions of imperial rule and transformed a largely peaceful resistance into an armed rebellion.

A View of the South Part of Lexington, 1775

Texts

- Diary entries of Matthew Patten, 1775.

- Announcement of the Battle of Lexington and Concord, 1775.

- Resolution to resist “force by force,” 1775.

- Rev. Jonas Clark, The Fate of Blood-Thirsty Oppressors, 1776 (excerpts).

[For more primary sources on the American Revolution, see Making the Revolution: America, 1763-1791.]

Text Type

Informational texts, each with a clearly stated purpose, moderately complex text structure and knowledge demands, and very complex language features. Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups (full list at bottom of page). Tier 3 words are explained in brackets.

Text Complexity

Grades 11-CCR complexity band.

For more information on text complexity see these resources from achievethecore.org.

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.1 (Cite strong and through text evidence to support analysis…)

- ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.4 (Determine the meaning of words and phrases…)

Advanced Placement US History

- 3.1 (IIC) (American Independence was energized by… popular movements…)

Teacher’s Note

The first text is from the private diary of a New England farmer. When news of the battles reached the small farming village of Bedford, New Hampshire, only one day after they took place, the townspeople had to respond to an unprecedented situation in neighboring Massachusetts. Matthew Patten, the head of a struggling Bedford family, recorded his response in his diary. Along with serving as a probate judge, Patten made shoes, tended cattle, and surveyed property. As you teach the diary, have your students focus on the “everydayness” of Patten’s life. Ask them to speculate on what it would take to move a man like him to anger and violence. Remind your students that Patten’s diary is a private document. Presumably, he wrote it for his eyes only. Ask them how Patten’s diary might differ from contemporary notions of what a diary is for. Ask your students if they keep diaries, and if they do, ask what sort of things they record in them. For Patten the diary was not a place to work out his thinking on the issues of the day or record his emotional ups and downs. It was simply a bare-bones documentation of his daily activities. Thus the drama of the moment is muted; in the passage we offer for discussion, the word “melancholy” is the only emotionally laden adjective he uses to describe what must have been a tense time. We can get at the passion of those April days in Bedford only through our imaginations. What was said at the town meeting? What emotions would lead a band of farmers to confront a professional army? What must it have been like to see your son and those of your neighbors march off to confront the British? The people of Bedford could have treated the Lexington militiamen as hotheads who deserved what happened to them, or they could have waited for more information. Patten and his neighbors did neither. They instinctively sensed that they had to go to the aid of those who were fighting for a cause that now included Bedford as well as Lexington, Concord, and Boston.

The next three documents are far more public than Patten’s diary. They illustrate how the speed of communication through newsprint enflamed Patriot zeal and turned a local incident into an American crisis.

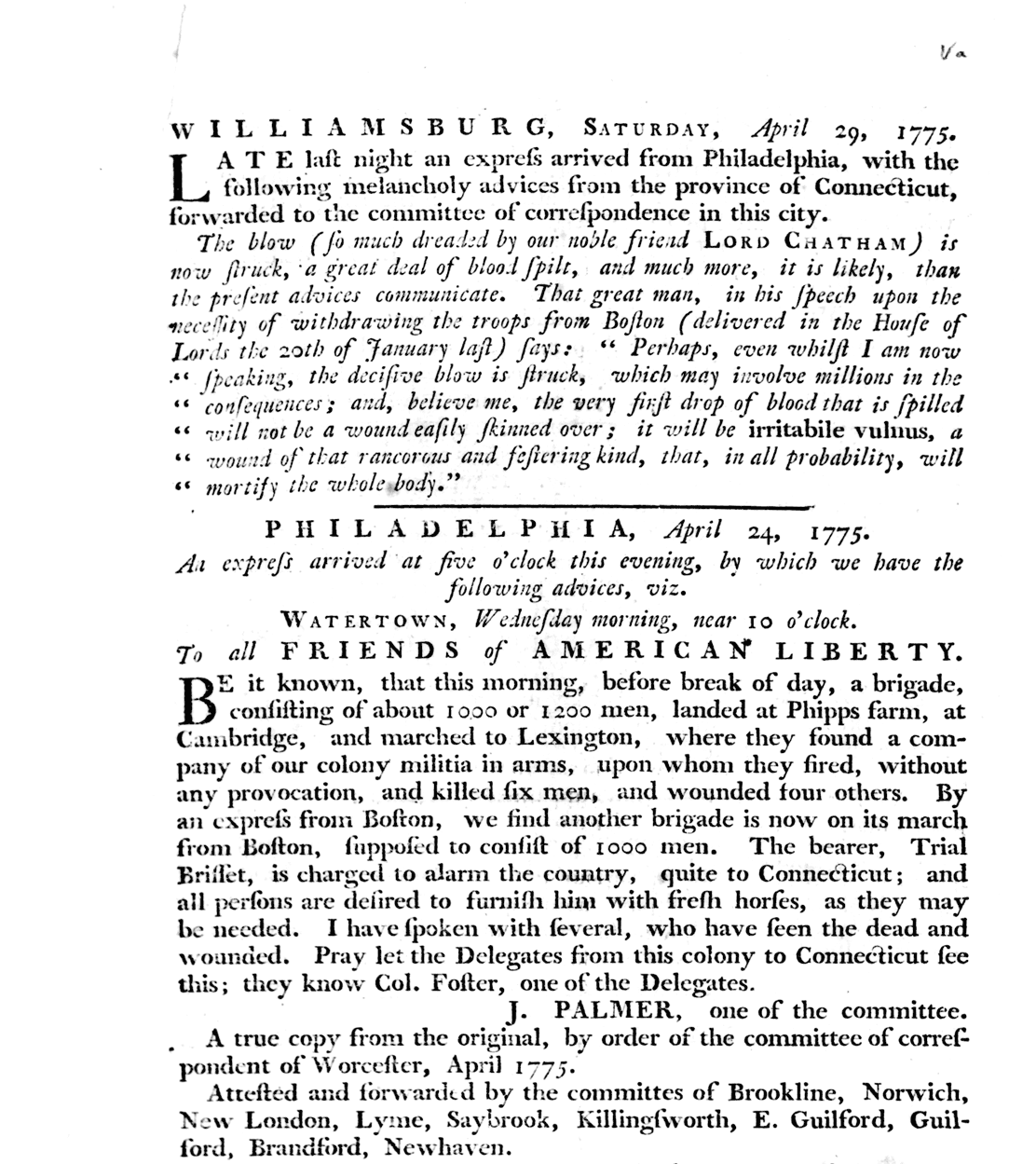

The second text is one of many hastily printed broadsides spreading word of Lexington and Concord throughout the colonies. Nine days after the battles, the news reached Williamsburg, Virginia, which printed its own “news bulletin” the next morning. Its handbill traces the path of the news from the first dispatch in Worcester, Massachusetts, on the morning of the battles, to the announcement the same day in Watertown, Connecticut, to the bulletin printed five days later in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania — which arrived in Williamsburg four days later. “The sword is now drawn,” exclaims the Philadelphia committee of correspondence in its dispatches (expresses) to the southern colonies, “and God knows when it will be sheathed.” What Matthew Patten described with deadpan calm the expresses relate with breathless urgency.

The third text is the resolution of a small North Carolina community, signed one month after Lexington and Concord, in which the citizens vow to “go forth and be ready to sacrifice our lives and fortunes to secure [the] freedom and safety” of the colonies. Like the Williamsburg express, the North Carolina resolution was copied from an earlier document that was passed from town to town, in this case from a resolution adopted three weeks earlier by the Charleston, South Carolina committee of correspondence. It is apparent from these resolutions that by mid-June, reports of the killings at Lexington and Concord forced people in the southern colonies to consider as they had never done before obligations to other Americans who lived hundreds of miles away. Whatever course they chose, they knew instantly that the events in Massachusetts had radically changed the character of the imperial confrontation.

The fourth text is from a sermon delivered in Lexington on the first anniversary of the battles at Lexington and Concord. It illustrates how the battles “sunk in,” how the Patriots interpreted them over the course of a tumultuous year. Delivered by Rev. Jonas Clark, the sermon reveals how he and others gave meaning to revolutionary violence now that the British had become, in their eyes, “bloodthirsty oppressors.”

Background

Contextualizing Questions

- What kind of texts are we dealing with?

- When were they written?

- Who wrote them?

- For what audience were they intended?

- For what purpose were they written?

Early on the morning of April 19, 1775, General Thomas Gage, commander of British forces in America, dispatched regular troops to Concord, Massachusetts, where spies informed him the Americans had stored weapons. The movement of so many soldiers out of Boston came as no surprise to the American insurgents. Paul Revere and others had warned the inland communities of the impending threat. About seventy members of the local militia gathered on the Lexington Green, intending to watch as the British marched past them on the road to Concord.

But after a British officer ordered the Americans to lay down their guns, someone fired, and after a few minutes, eight colonists were dead. The news spread quickly throughout the region. Within hours hundreds of Americans confronted the British at Concord. The death of the Lexington militiamen and the pitched battle that developed as British troops retreated to Boston electrified the communities from New Hampshire to Georgia. People who had assumed that resistance to taxation without representation involved peaceful strategies such as boycotts and petitions dramatically discovered that the imperial crisis had taken a violent turn. Ordinary men and women suddenly and decisively came forward and transformed protest into a massive insurgency.

During the 1760s and early 1770s Americans spoke eloquently about abstract principles such as liberty and rights. After 1775 the political landscape changed radically. Unhappy colonists discovered that successful revolutions—the mobilization of sufficient numbers of ordinary people to sustain resistance against a powerful empire—required an emotional component. American historians seldom mention anger and hate as aspects of revolutionary ferment, preferring to concentrate on reasoned academic texts written by men such as John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and John Dickinson. These pamphlets undoubtedly served to instruct the colonists about their rights as citizens and British subjects. What goes missing from this perspective is the sense of outrage that propelled the revolution forward.

Text Analysis

Diary entries of Matthew Patten, April 18-21, 1775

Close Reading Questions

1. How would you describe Matthew Patten’s diary? How does it differ from 21st-century ideas of what a diary is for?

Patten’s diary is simply a listing of daily activities. It is different in that it does not list any emotional responses, personal reflections, or questions.

2. Can we trust Patten’s diary? Why or why not?

The diary can be trusted to reflect the activities of a farmer in New England. Since Patten wrote for presumably himself, he had no reason to alter his activities. And he does not seem to have a political agenda, if he did he would probably use more emotionally charged words.

3. How does Patten’s matter-of-fact presentation affect our perception of Bedford’s preparation for war?

A matter-of-fact presentation presumes that Bedford had prepared for this possibility, as they did not spend much time discussing or determining who was at fault or waiting for more information. They responded immediately.

4. What impact did the news from Lexington and Concord have upon Bedford?

The men met that evening and 20 or more men left to “assist them.” Patten reminds us that notwithstanding the events of Lexington and Concord farm life goes on, as he continues to describe his daily activities.

5. What does it suggest that men from surrounding towns joined Bedford men on the march to Concord?

It suggests a common identity and cause with men from different towns. Men would see themselves identified as more than simply men from a particular town but also as men from the area.

6. What does the speed with which the region’s men organized themselves suggest?

It suggests that they saw a common threat in the actions of the British. It also suggests that there was a system by which men would look after their neighbors so that if a man was away from his home there would be someone who would look in on his family.

7. Would it not have been wiser for Matthew’s son and his friends to have waited a few days before rushing off to join the American army?

It would have been surprising if the young men had waited. The men reacted immediately to the British threat, assuming that if they did not do so a reaction might not be possible and further British restrictions would follow. In addition their swift reaction to join suggests the emotional patriotism of the young men to help defend those seen as their “countrymen.”

8. What does Patten’s use of the term “our Countrymen” suggest?

It suggests a common identity with the men of Concord. With a common identity it makes it natural that the men of the area would come to the aid of the town. It also suggests a common defense is the rational response to British aggression.

9. From this passage what can you infer about the role women played in the mobilization?

The women kitted out the men before they left, “bakeing bread and fitting things for him and john Dobbin.”

19th — I got james Orr to make two hoops for our great Kittle one of them was my iron the other was Sheds and he made part of a chain for my Cannoe of my iron and writ a deed from Alexander McCalley to his son Alexander and I took the acknowledgement unpaid.

20th — I Recd [received] the ,Melancholy news in the morning that General Gages troops had fired on our Contrymen at Concord yesterday and had killed a large number of them our town was notified last night We Generay met at the meeting house about 9 of the Clock and the Number of twenty or more went Directly off from the Meeting house to assist them And I came to Sheds and james Orr made me a great wheel Spindle of my Steel and he mended the Ear of a little kittle and finished the chain for my cannoe he found iron for near a quarter of the chain the rest was mine And our john came home from being down to Pentuckett and intended to Sett off for our army to morrow morning and our Girls sit up all night bakeing bread and fitting things for him and john Dobbin

21st — our john and john Dobbin and my bror [brother] Samuell two oldest sons sett off and joyned Derryfield men and about six from Goffestown and two or 3 more from this town under the comand of Capt john Moor of Derryfield they amounted to the No of 45 in all Sunkook men and two or three others that joined them marched in about an hour after they to 35 there was nine more went along after them belonging to Pennykook or thereabouts and I went to McGregores and I got a pound of Coffie on Credit

Excerpts from the Williamsburg Committee of Correspondence

Close Reading Questions

10. How would you imagine the readers of this report would react?

Readers of this report would be horrified that the British had killed American colonists. They would be angry and confused as to what may come next. They would be fearful of the report that another British brigade is marching from Boston. They would wish to help the rider and provide him with horses as requested.

11. What details would evoke the strongest response?

The detail that would evoke the strongest response would include the fact that the British “fired, without any provocation, and killed six men, and wounded four others.” Accompanied with the fact that another British brigade is on the march, this would be frightening.

12. How do the presumed author, J. Palmer, and the distributors of this dispatch seek to assure readers of its credibility?

Palmer states, “I have spoken with several, who have seen the dead and wounded…” The chain of correspondence contributes to the credibility of the information.

13. Why was it important to list the Committees that forwarded the dispatch?

This establishes the chain of correspondence and lends credibility to the report. The purpose of the Committees of Correspondence were to keep colonies updated on news and events, and by tracking the path of the report it lets the reader be assured of the veracity of the report. It also lets the reader know that the information is being spread far and wide.

14. Who are the “Friends of American Liberty”?

That would be anyone who supported the American cause and opposed British tyranny.

15. What does this bulletin suggest about the colonists’ readiness for a British attack?

The bulletin states that they were attacked “without any provocation.” The colonists were not prepared militarily for attack-colonial militia was no match for a British brigade.

WILLIAMSBURG [Virginia], SATURDAY, April 29, 1775.

LATE last night an express [news bulletin sent by stagecoach or person on horseback] arrived from Philadelphia, with the following melancholy advices [news] from the province of Connecticut, forwarded to the committee of correspondence in this city. . . .

PHILADELPHIA [Pennsylvania], April 24, 1775.

An express arrived at five o’clock this evening, by which we have the following advices, viz. [namely]:

WATERTOWN [Connecticut], Wednesday morning, near 10 o’clock.

To all FRIENDS of AMERICAN LIBERTY.

Be it known, that this morning, before the break of day, a brigade, consisting of about 1000 or 1200 men, landed at Phipps farm, at Cambridge [Massachusetts], and marched to Lexington, where they found a company of our colony militia in arms, upon whom they fired, without any provocation, and killed six men, and wounded four others. By an express from Boston, we find another brigade is now on its march from Boston, supposed to consist of 1000 men. The bearer, Trial Bisset, is charged [ordered to] to alarm [warn] the country, quite [all the way] to Connecticut; and all persons are desired [requested] to furnish him with fresh horses, as they may be needed. I have spoken with several, who have seen the dead and wounded. . . .

J. PALMER, one of the committee.

A true copy from the original, by order of the committee of correspondence of Worcester [Massachusetts], April 1775.

Attested and forwarded by the committees of Brookline [Massachusetts], Norwich, New London, Lyme, Saybrook, Killingsworth, E. Guilford, Brandford, Newhaven [Connecticut towns].

Excerpt from the Resolution signed by citizens of Cross Creek,

Cumberland County, North Carolina, 1775

Close Reading Questions

16. Judging from this resolution, what impact did the news from Lexington and Concord have on the inhabitants of Cumberland County, North Carolina?

It served as a call to prepare for action. They were immediately bound together and determined to resist force “by force” against “every foe.”

17. Do you think everyone in Cumberland County agreed with the sentiments expressed in the resolution?

It is improbable that everyone agreed. These are strong words, a call to military action, and it would have been rare for everyone in the community to agree.

18. What does the author mean by “instigated insurrections”?

These are uprisings created on purpose. This could directly refer to the fact that the British marched upon Concord in order to seize the munitions gathered there. [NOTE: Colonists also accused the British of inciting the Native Americans to rise up against the colonies, and this could be an allusion to that as well.]

19. Why should people in North Carolina care about the rights and liberty of Massachusetts farmers? What reasons does the resolution provide?

The NC citizens cite that they are bound “by that most sacred of all obligations, the duty of good citizens towards an injured country.”

20. Since the Continental Congress had not declared independence at this point, what is the meaning of an “injured country”?

In this context it means a country whose citizens have been denied their rights by their own government. This has injured the fabric that ties a citizen to his government.

21. Why did the inhabitants of this community appeal to “religion and honor”?

Religion and honor were basic and powerful motivators and ones that everyone could understand and to which they could respond.

22. To what extent is this resolution a response to the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and to what extent is it designed to provoke a response to the battles?

It is for the most part designed to provoke a response to the battles. While the resolution begins with a reference to the battles it quickly shifts to a statement of resolve to associate and when called resist by force.

23. What does this resolution commit the men of Cumberland County to do?

These men will “associate as a band in her defense against every foe” and “will go forth and be ready to sacrifice our lives and fortunes to secure her freedom and safety.” They will organize and be ready to fight “whenever our Continental or Provincial Councils shall decree it necessary.”

Excerpt from Reverend Jonas Clark’s sermon, “The Fate of Blood-Thirsty

Oppressors”, preached in Lexington, Massachusetts, April 19, 1776, on the

first anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord

Close Reading Questions

24. Why does Reverend Clark urge his congregation to acknowledge God’s hand in the battles of April 19th, 1775?

By acknowledging the hand of God he reminds his church that God calls on them to avenge the blood of the slain. This appeals to their sense of ethical responsibility to God.

25. Identify the specific elements that Reverend Clark uses to rouse the emotions of his congregation.

His diction is emotionally charged—world like murder, war, murderers, cut-throats, cruelty, and barbarity appeal to the emotions of his audience. Through imagery he personifies the blood of the slain in the phrase, “from thence does they blood cry until God for vengeance from the ground.”

26. Was it fair for Reverend Clark to call the British troops “murderers” and “cut-throats”?

It was not accurate from an historical sense, but it contributed to his objective in the sermon.

27. What did Reverend Clark mean when he said that April 19th, 1775, was the beginning of a new AMERICAN WORLD?

He reminded his audience that from that point forth America was different. That event changed the relationship between America and Britain in a basic way and regardless of how the war ended, that relationship would never return to what it had been before.

28. According to Reverend Clark, what would a colonist have to do to avenge the killing of local militiamen?

They would join the army and fight the British.

29. Could the people who listened to Clark’s sermon turn back and restore the old imperial order?

They could not. He clearly states that April, 1775, will be dated “in future history, THE LIBERTY or SLAVERY of the AMERICAN WORLD.” There was no going back. The future would be either liberty or slavery.

Follow-Up Assignment

Ask your students to analyze Matthew Patten’s diary entries from April 1775 to May 1776 ![]() and identify ways in which his life changed after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Write an essay citing specific examples of new activities and concerns in his diary entries and explain why he focuses on them.

and identify ways in which his life changed after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Write an essay citing specific examples of new activities and concerns in his diary entries and explain why he focuses on them.

VOCABULARY pop-ups

- melancholy: sad, mournful

- commencement: start, beginning

- arbitrary: made by personal whim, not based on any reason or system

- imposition: unfair or unwelcome demand or burden

- instigated: started or brought about on purpose

- insurrection: revolt, uprising

- foe: enemy, opponent

- provocation: incitement, something that causes a strong response in another person or persons

- yonder: over there [“that field over there”]

- brethren: brothers, i.e., fellow men [humans, Patriots, etc.]

Images:

– Ralph Earl (artist), A View of the South Part of Lexington, hand-colored engraving by Amos Doolittle, 1775 (detail). Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Digital ID 54390.

– Broadside announcing the Battle of Lexington and Concord, published by the Williamsburg, Virginia, Committee of Correspondence, April 29, 1775. Digital image from online collection Early American Imprints, American Antiquarian Society with Readex/Newsbank, Doc. 14602, from the original in the Library of Congress. Reproduced courtesy of the Library of Congress and the American Antiquarian Society.