Advisor: Michael P. Gaudio, Associate Professor of Art History

, University of Minnesota.

Copyright National Humanities Center, 2011

Lesson Contents

How did Europeans interpret the New World through their earliest visual depictions?

Understanding

John White’s depictions of Virginia brought a striking naturalism to the visual representation of America even as they were shaped by European cultural habits and preconceptions.

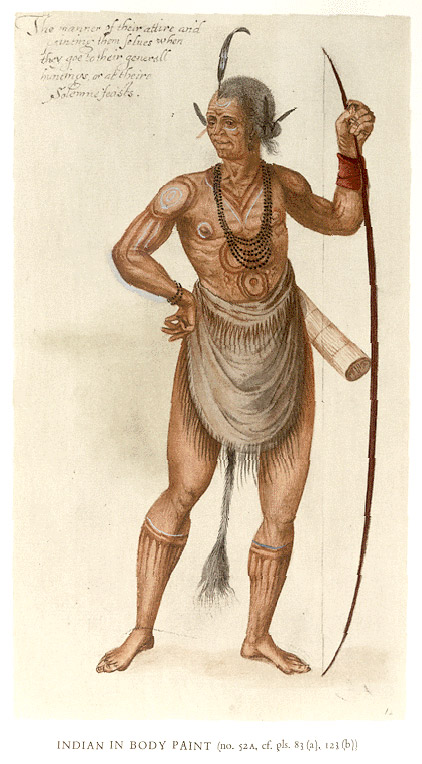

John White, Indian in Body Paint,watercolor, ca. 1585

Images

Pair #1:

- John White, Indian in Body Paint, watercolor, ca. 1585

- Depiction of Blemmyes (mythical headless men), engraving in Raleigh, Discovery of Guiana, 1595 (1603 German ed.)

Pair #2:

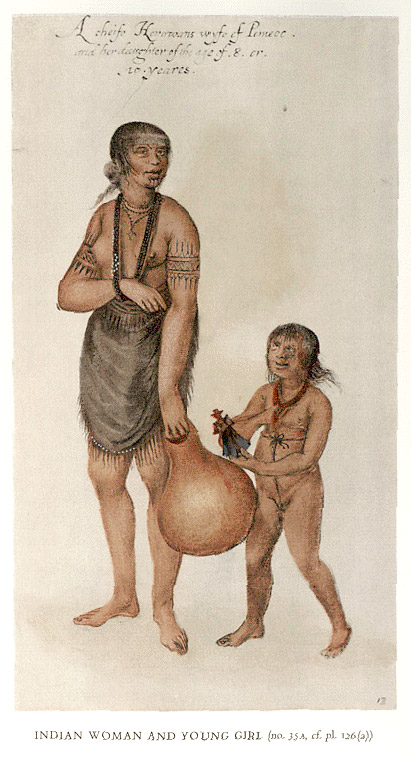

- John White, Indian Woman and Young Girl, watercolor, ca. 1585

- Theodor de Bry, Their Solemn Ritual in Consecrating a Deerskin to the Sun, engraving after Le Moyne watercolor, 1591

Pair #3:

- John White, Indian Conjuror (The Flyer), watercolor, ca. 1585

- Workshop of de Bry, The Conjurer, engraving, 1590

[For more resources with early New World imagery, see Illustrating the New World, Part One and Part Two, in American Beginnings: The European Presence in North America, 1492-1690 from the National Humanities Center.]

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.7 (Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words in order to address a question or solve a problem.)

Advanced Placement Language and Composition

- Analyzing graphics and visual images both in relation to written texts and as alternative forms of text themselves

Advanced Placement US History

- Key Concept 1.2 (IIIA) (mutual misunderstandings between Europeans and Native Americans…)

Teacher’s Note

Each of the three image pairs is a visual comparison that asks you to consider one of John White’s watercolors of Carolina Algonquians in relation to another sixteenth-century depiction of New World peoples. The comparisons offer an opportunity to consider the general problem of how artists attempted to make the cultures of New World peoples intelligible to their European audiences. They are also an occasion to consider what is unique about White’s depictions.

When teaching the comparisons, evoke for your students the situation of being in a place that the Virginia expedition’s members were encountering for the first time and in which they confronted the significant challenge of communicating with the native inhabitants. That challenge was exacerbated by a variety of factors including a lack of familiarity with the climate and topography, dependence on the Algonquians for food, and the terrible impact of European germs (smallpox) on native populations. Within this fragile and often tense situation, White’s task was to communicate a visual understanding of the Algonquians in a way that might promote interest and investment in the Virginia colony. To what extent do the pictures convey such understanding, and to what extent do they suggest the limits of European understanding?

It is important to recognize that artists, no less than writers, must speak in a language that both they and their audience are familiar with. The first comparison focuses on the different visual languages employed by White and by an artist who illustrated a 1603 edition of Sir Walter Raleigh’s account of his voyage to Guiana (a voyage that took place in 1595, several years after the failure of the Virginia colony). Explore the contrast between White’s naturalistic depiction of an Algonquian warrior in body paint and a sensationalist image that shows the inhabitants of Guiana as “Blemmyes,” or people with heads in their chests that belonged to the tradition of the “monstrous races” derived from Herodotus and Pliny. But also consider the ways in which White was responding to the expectations of his European audience.

The second comparison involves two representations of encounter between Europeans and natives. One of the images, designed by the French artist Jacques Le Moyne who had traveled to Florida in 1564 as part of an effort to establish a French Protestant colony, shows an encounter between French soldiers and Timucuan Indians and invites you to consider likeness and difference between the two cultures. In his watercolor of an Algonquian mother and child, White confronts encounter more obliquely, by placing an English doll in the hand of the young girl.

The final comparison focuses on one of Theodor de Bry’s re-interpretations of a John White watercolor. De Bry’s engraving is based on White’s depiction of an Algonquian shaman, or medicine man, which White entitled “The Flyer.” De Bry re-names the shaman as “The Conjuror” and includes a caption that portrays him as a disreputable and untrustworthy magician, of a kind that would have been familiar to European audiences (see below, pair #3). This comparison is an occasion to consider how text and captions can transform the way an audience interprets an image.

This lesson is divided into two parts, both accessible below. In addition to close reading questions, interactive exercises and an optional followup lesson accompany the images. The teacher’s guide includes a background note, the image analysis with responses to the close reading questions, access to the interactive exercises, and the follow-up assignment. The student’s version, an interactive PDF, contains all of the above except the responses to the close reading questions and the follow-up assignment.

Teacher’s Guide (continues below)

|

Student Version (click to open)

|

Background

On April 9, 1585, a military expedition set sail from Plymouth with the goal of fortifying and surveying the New World territory Sir Walter Raleigh had named “Virginia” after Queen Elizabeth. One member of this expedition, John White, who later became governor of the failed Roanoke colony, had the task of recording Virginia in pictures. During the summer of 1585 White produced a remarkable collection of watercolors, now housed in the British Museum, that describes the native peoples, natural history, and geography of the region. Thanks to Theodor de Bry’s engravings of these watercolors, published in 1590, White’s pictures would go on to have a profound impact upon how Europeans imagined nature and society in North America.

Like any artist traveling to the New World in the sixteenth century, John White faced the challenge of depicting a world unknown to Europeans. While the accounts of Greek and Roman authors like Herodotus and Pliny had traditionally provided models for representing the peoples living at the farthest reaches of Africa and Asia, these writers made no mention of America. How could artists make the New World comprehensible in the Old? In 1620 the English philosopher Francis Bacon, frustrated with the dependence of his contemporaries on ancient authors, called upon them to build new knowledge through the direct evidence of the eyes: “all depends on keeping the eye steadily fixed upon the facts of nature and so receiving their images simply as they are.” In the spirit of Bacon, White’s watercolors of Virginia keep our eyes “steadily fixed upon the facts.” At the same time they offer ample occasion to reflect on the visual strategies through which an artist familiarized the New World for his European audience.

Image Analysis

Pair #1

The Natives were seen as non-human, very unlike the Europeans. It conveys the idea that the Natives were extremely different—more so than anything the Europeans had perceived before.

2. How does White convey a sense of cultural and racial difference?

White shows body paint and tattoos, limited clothing, a “tail” in the back of the warrior, and feathers in his hair. The skin is darker than that of most Europeans. European warriors of the time were clothed in metal armor, much more restrictive and covering their bodies.

3. How do you think White’s audience would have responded to some of the details of his painting, such as the Algonquian’s body paint or the tail attached to his garment?

They would have considered them heathen, animal-like. They would have assumed this warrior had no sophisticated culture and would be at best only a minor military threat.

4. What does the gesture of the Algonquian with hands on hips suggest about his character? (Compare with a contemporary portrait of Sir Walter Raleigh and his son.)

He is balanced comfortably, assertive, and experienced. But his wrist is reversed from the portrait of Raleigh, implying a different culture or stance from Raleigh.

5. Unlike the illustration of the Blemmyes, White’s Algonquian warrior is not shown in a landscape or in a context of any sort. Why would he have chosen to isolate his subject like this?

He wants to focus the viewer upon the warrior and the details of the warrior himself rather than the context around him.

6. White’s caption reads: “The manner of their attire and painting themselves when they go to their general huntings, or at their solemn feasts.” Why might White’s English audience — which would have included the Queen, Raleigh, and other members of the aristocracy — have been interested in the Algonquians’ “attire” on such occasions?

Those types of events are something to which that audience can relate. They could compare the attire of the warrior with their own. This would further emphasize the differences in culture and imply that the Algonquian culture was simplistic.

Compare the details and captions of two early illustrations of Native Americans.

7. Do the two images offer differing interpretations of the peoples of the New World? Explain your answer.

Answers will vary. They are different; the Blemmyes image conveys a hideous monster that cannot be understood, invoking fear and revulsion. The White image conveys differences in culture and habits but is clearly a human.

Pair #2

In the White image a woman is carrying a pot, perhaps to get water. In the Le Moyne image, men are worshipping an image on a pole and another is showing the ritual to French soldiers.

9. What kind of encounter do we witness in the Jacques Le Moyne image? In what ways does Le Moyne suggest similarity between the two cultures? (Note for instance the relationship between the fashionable slashed clothing of the French soldiers and the tattoos of the Timucuan Indians.) In what ways does Le Moyne suggest difference?

In the Le Moyne image the encounter is part of the Native culture. Similarities include the decoration on the French uniforms and the tattoo patterns on the Natives. Ornaments or bows just below the knee are on both Natives and the French. Differences are apparent based upon the behavior of the Natives worshipping the pole, the amount of dress between the two groups, and the fact that the French have weapons (pikes) with them. The French have facial hair and foot coverings while the Natives do not.

10. What does Le Moyne’s picture suggest about the role that religion played in the encounter between Europeans and Native Americans?

The picture suggests that religion was important to the Natives but it was not the Catholic religion. This could be a conflict between the two groups. The French facial expressions looks horrified at the native practice.

11. How does each picture confront the issue of contact and communication between Europeans and Native Americans? (Note that in the John White watercolor, the young girl holds an English doll in her hand.)

The White image suggests a more informal contact, depicting family life and little antagonism. The Le Moyne image shows only males, some armed, and depicts a more formal contact with the potential for uncomfortable communication. The White image is something with which Europeans could identify, while the Le Moyne image is not.

12. Why might John White focus on the relationship between a youth and an adult? What kind of relationship does he suggest between the two figures?

He suggests mother and daughter. He is depicting a relationship with which Europeans could identify and is reminding his audience that the Natives are organized around families.

13. Why might John White be interested in the receptivity of Native Americans to a European doll? What does the picture suggest about the potential for the Algonquians to adopt English customs?

The gift of the doll allows the natives to understand what a female in European culture looks like, as no European females were with the party. The fact that the child accepted the gift suggests that the Algonquians might be open to English culture.

14. Compare White’s picture of the mother and daughter with the portrait of Raleigh and his son. In what ways is White drawing upon standard conventions of European portraiture?

Both depict a parent and child, with the child subordinate to the parent. In the Raleigh portrait his son is mirroring Raleigh’s posture. In the White drawing the child is reaching for the pot held by the mother as if to mirror and share her activity.

Pair #3

The figure seems to be in the process of flying forward. He might be a messenger.

16. Look closely at the details of White’s picture: the bird attached to the figure’s head, the pouch at his side, the outstretched and waving arms. What do these visual details tell us about this individual?

The figure is equipped to run, carry small items or messages, and go quickly (as indicated by the bird attached to his head).

17. Do you see similarities between White’s “Flyer” and contemporary representations of the Greco-Roman god Mercury, like this one? Do you think White was using Mercury as a model? Why?

Similarities include wings on head, running posture, arms out. This is not a natural posture. He may have been using Mercury as a model in order to indicate that this person was a messenger, as was Mercury.

18. In the engraving, what visual changes have been made to the watercolor, and what is the significance of these changes?

A background has been added to the image, and this puts the subject more into context. Rather than the viewer focusing upon the figure the viewer now sees the figure in action. It encourages the viewer to ask where he is going or where he has been and speculate as to the message he may be carrying.

19. How does the title change from “flyer” to “conjuror” change the meaning of the image?

The title “flyer” indicates someone on an important mission or performing a specific task. The title “conjuror” suggests more someone who is “unnatural,” or perhaps a bit crazy. Harriot suggests the person has league with the devil. The figure goes from being a member of the tribe with a specific role to someone who may be dangerous.

20. Carefully read the caption to the engraving, which was written by White’s partner in surveying Virginia, the English scientist Thomas Harriot: “They have commonly conjurers or jugglers which use strange gestures, and often contrary to nature, in their enchantments: For they be very familiar with devils, of whom they inquire what their enemies do, or other such things. They shave all their heads saving their crest which they wear as other do, and fasten a small black bird above one of their ears as a badge of their office. They wear nothing but a skin which hangs down from their girdle, and covers their privates. They wear a bag by their side as is expressed in the figure. The Inhabitants give great credit to their speech, which oftentimes they find to be true.” Note that the caption was written during a time when belief in witches and magicians was widespread throughout Europe. How does Harriot’s own cultural and religious background shape his understanding of the Algonquian medicine man?

Harriot assumes that because the medicine man behaves differently or at the edge of the culture he is in league with the devil. This type of person was often accused of witchcraft in Harriot’s culture.

21. Do you think that describing this figure as a “conjuror” would have been an effective means for a European audience to understand the shaman’s role as a go-between who moves between the human and spirit worlds?

The title conjuror would not be understood by a European audience in the sense it was used in the native culture. Europeans would see it as an evil force rather than one who connects the human and spirit worlds. In European cultures that role was reserved for priests.

Follow-Up Assignment

While de Bry’s engravings achieved immediate and widespread fame in Europe in the 1590s and early 1600s, John White’s original paintings were not published until the twentieth century. And neither were two image collections of Canada and the Caribbean that, like White’s drawings, were created by Europeans in the New World and were held in private collections for centuries. Read more background on these works before you begin studying the images.

- CAROLINA, 1580s. Paintings of the Indians, plants, and animals of present-day coastal North Carolina, created by John White during the attempt to settle an English colony on the Atlantic coast. Focus on the depictions of the Algonquian Indians.

- CARIBBEAN, 1580s. Paintings of the Indians, plants, and animals of the West Indies, perhaps drawn by two or more crewmen sailing with Sir Francis Drake. Focus on the depictions of the Indians on pp. 7-10, 13-14.

- CANADA, 1670s. Drawings of the Indians, plants, and animals of French Canada by a French Catholic priest, Louis Nicolas. Focus on the depictions of the Indians, pp. 2-9.

Compare and contrast the three collections of eyewitness depictions of the New World. How do they differ from the engravings created by Theodor de Bry, who had never visited the New World and who based his depictions on others’ drawings. Use the questions below and the graphic organizer to organize your ideas. Present your responses and conclusions in an illustrated essay, PowerPoint presentation, narrated video, classroom exhibit, etc.

- What are your first reactions to the drawings? How do they surprise, intrigue, or puzzle you? Do you like them? Why or why not?

- What identifies the images as eyewitness depictions of the New World?

- How do they differ from the engravings by Theodor de Bry and others who adapted the eyewitness images for publication in Europe?

- What identifies the images as Europeans’ depictions of the New World?

- What did the artists find important to draw and describe? Why do you think they found these things important? Do you think they planned to publish their collections? Why or why not?

- If these eyewitness collections had been published in the 1500s and 1600s, how might they have influenced European notions of the New World and its inhabitants?

For more visual representations of the New World, see the following resources in the primary source collection American Beginnings: The European Presence in North America, 1492–1690, from the National Humanities Center.

- De Bry’s engravings of the Algonquian Indians, Roanoke region, 1590, from John White’s watercolors

- De Bry’s engravings of the Timucua Indians, Florida, 1591, from the watercolors of Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues

- John White’s watercolors of an Inuit family, northern Canada, 1577

- Spanish depictions of the Aztec, 1500s: follow the links to paintings in Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520-1820

Vocabulary Pop-Ups

*Because there is no text for this lesson, vocabulary was pulled from the background note and the questions.

- fortifying: strengthening

- surveying: examining

- watercolor: a painting method using a transparent paint

- engraving: a print made from an engraved plate

- comprehensible: able to understand

- ample: more than enough

- solemn: serious and formal

- interpretation: an explanation

Images:

- John White watercolors, ca. 1585. The Trustees of the British Museum. Reproduced by permission.

- Indian in Body Paint (The manner of their attire…). Image 00025875001.

- Indian Woman and Young Girl (The cheife Herowans wyfe…). Image 00025876001.

- Indian Conjurer (The flyer). Image 00025879001.

- Images from Archive of Early American Images, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University. Reproduced by permission.

- G. van Veen (de Bry workshop), The Conjurer, engraving after John White, in Thomas Hariot, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, 1590. Call No. J590 B915v GV-E.I [F] / 2-SIZE.

- Depiction of Blemmys [Blemmyae], engraving in a 1603 German edition of Sir Walter Raleigh, Discovery of Guiana, 1595. Call No. T7d V3b.

- Theodor de Bry, Their Solemn Ritual in Consecrating a Deerskin to the Sun, engraving after watercolor by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, in Le Moyne, Brief Narration of Those Things Which Befell the French in the Province of Florida in America, 1591. Courtesy of the Florida Center for Instructional Technology, University of South Florida.