Advisor: Eliza Richards, Associate Professor of English, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, National Humanities Center Fellow.Copyright National Humanities Center, 2014

Lesson Contents

Why does Aylmer, the protagonist of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s story “The Birthmark,” undertake his fatal experiment?

Understanding

Aylmer, the protagonist of Hawthorne’s “The Birthmark,” undertakes to remove the blemish from his wife’s cheek to satisfy his own spiritual strivings and to redeem what he sees as a failed career.

Text

Nathaniel Hawthorne, “The Birthmark”, 1843.

Text Type

Literary fiction; short story.

In the Text Analysis section, Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups, and Tier 3 words are explained in brackets.

Text Complexity

Grades 11-CCR complexity band.

For more information on text complexity see these resources from achievethecore.org.

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.3 (Analyze the impact of the author’s choices regarding how to develop and relate elements of a story including how the characters are introduced and developed.)

Advanced Placement English Language and Composition

- Reading fiction

- Analyzing and interpreting samples of purposeful writing

- Writing for a variety of purposes

Teacher’s Note

This lesson explores some of the motives that drive Aylmer to attempt to remove the blemish from his wife’s cheek. Undoubtedly, you and your students will identify several, but in this lesson we focus on two: his striving for a more spiritually refined life and his desire to reconcile his private sense of failure with his public image of success.

To help with reading, we have uploaded a version of the story annotated with vocabulary assistance and comprehension questions. It is a Word document, so you can easily tailor it to your needs through revisions and additions.

The first interactive exercise focuses on vocabulary development. The second, well-suited for individual or small group work, asks students to outline a brief paper on the following thesis:

Aylmer undertakes to eliminate the birthmark from his wife’s cheek because in so doing he would realize his greatest scientific achievement and rescue his career from the failure he privately considers it to be.

The exercise gives students practice in structuring an argument, identifying textual evidence, and articulating connections between elements of an argument.

This lesson is divided into two parts, both accessible below. The teacher’s guide includes a background note, the text analysis with responses to the close reading questions, and access to the interactive exercises. The student’s version, an interactive worksheet that can be e-mailed, contains all of the above except the responses to the close reading questions.

Teacher’s Guide (continues below)

|

Student Version (click to open)

|

Background

Background Review Questions

- When was the story published?

- When was it set?

- What kind of scientist is Aylmer?

- What is the focus of this reading of the story?

At first glance “The Birthmark,” published in 1843, seems like a simple story with, as the narrator tells us, a “deeply impressive,” and presumably easily understood, moral. Yet, as with all of Hawthorne’s mature stories, when we look closely, we discover that “The Birthmark” is not as simple as it seems. The narrator — cool and detached, like many of Hawthorne’s narrators — leaves us with questions. How, for example, can Aylmer be “proficient in all branches of” science when his journal is a record of failure? Why does Georgiana drink the potion when she has come to doubt Aylmer’s skill? And then there is perhaps the most intriguing question of all: why does Aylmer undertake to eradicate the birthmark? The analysis we offer here explores that last question and in so doing reveals the complexity of this “simple” tale.

Since we are going to focus on Aylmer, it might be useful to say a few words about him as a scientist. The narrator describes him as a natural philosopher, which was what people called scientists in the late 1700s, when, it appears, the story is set. Although Aylmer worked in a variety of fields — geology, physiology, and physics, to name a few — he seems to have been essentially a chemist, an alchemist, to be more precise. Alchemy, the forerunner of modern chemistry, dates from ancient times. Alchemists tried to understand the composition of the material world by mixing and refining elements. According to scholars, this work led to the discovery of some useful products. However, there was also a spiritual, philosophical, speculative side to alchemy that led practitioners to search for compounds that would achieve physical impossibilities, like turning lead into gold, and even guarantee immortality. By the late eighteenth century that strain of alchemy was no longer taken seriously, and it is that strain in which Aylmer seems to work.

In this story Hawthorne marries an aging alchemist, whose best work may be behind him, to a nearly perfect young woman. Nearly perfect. What sort of challenge do you think that “nearly” would pose to a man who has been trying to perfect things most of his life?

Text Analysis

Setting the Stage: Paragraph 1

Close Reading Questions

Learn definitions by exploring how words are used in context.

1. The opening lines of a work of fiction bear close study because often in them an author will reveal important elements like setting or theme. In sentence 1 the narrator establishes part of the story’s setting. What does he include, and what does he leave out? Why might he make this omission?

He includes the time of the story but omits the place. Thus the narrator erases the wider world from the story. This helps create the closed, isolated environment in which Aylmer and Georgiana live. By making “The Birthmark” “placeless,” the narrator offers no locational context that might situate Aylmer and Georgiana in a community.

2. When is the story set?

If we can assume that the narrator is speaking at the time of the story’s publication, 1843, then the story would be set in the late 1700s.

3. Why does the narrator refer to the protagonist simply as a nameless “man of science”?

He wants to place immediate emphasis on Aylmer’s chief characteristic. The protagonist is first and foremost a “man of science.”

4. What opposition does the narrator establish in sentence 1?

An opposition between the spiritual and the scientific or “chemical.”

5. What does the word “chemical” refer to here?

It refers to the world of soot, fumes, and acid in which Aylmer has lived and worked most of his life.

6. Sentences 1 and 2 tell us that the story is set at a key moment of change in Aylmer’s life: he has just gotten married. Whenever a story focuses on newlyweds, what thematic questions immediately arise?

How will they get along? How will they adjust to each other? Will the marriage work?

7. What do sentences 1 and 2 suggest about the way Aylmer’s life will change now that he is married?

Sentence 1 tells us that his marriage has introduced him to a realm of spiritual or emotional experience far different from and more attractive than the “chemical” realm in which he had spent most of his life. Sentence 2 suggests that he hopes to refine himself, to put some distance between himself and the grime and soot of his work.

8. Sentence 1 tells us that Aylmer has established a spiritual relationship. Sentence 2 tells us what that relationship is, his marriage, which has come after a process of refinement — he left his lab, dusted off the soot, scrubbed his hands, and only then married Georgiana. These sentences suggest what Georgiana means to him. What is that meaning?

She represents his connection to a more spiritual existence. She is the culmination of his spiritual striving, the end of his quest to refine his life and connect to a higher level of spirituality, or as the narrator says in paragraph 56, “to quench the thirst of his spirit.”

An 18th Century Wedding

Paragraph 1 cont’d

An opposition between the love of science and the love of woman.

10. In sentence 4 Hawthorne explains why the love of science might rival the love of woman. State the reasons in your own words.

Students will, of course, come up with various paraphrases, but essentially Hawthorne suggests that science, like love, can nourish both the mind and the heart, but it may offer something more alluring than love in the promise of acquiring the power to create new worlds.

11. Why is sentence 5 an odd statement for the narrator to make?

The narrator is omniscient, yet here he admits that he does not know a key aspect of Aylmer’s attitude toward science. Why? Paragraphs 22 and 51, analyzed below, suggest an answer.

12. In sentences 6 and 7 the narrator adds the final details to the stage setting before flipping the switch on the action. Although this is a time of change for Aylmer, what will not change for him?

His devotion to science will not change.

13. What question does the narrator raise in sentence 7?

Which will prove stronger, Aylmer’s love for his wife or his love of science?

14. What themes has the narrator introduced in this opening paragraph?

- The opposition of spirit and science

- Aylmer’s striving for a more spiritual life

- The role of Georgiana as Aylmer’s link to a life of greater spiritual refinement

- The fate of Aylmer’s and Georgiana’s marriage

- Aylmer’s faith in the power of science to control nature

- Love for a woman v. love of science

Paragraph 3

He refers to it merely as a “mark,” a neutral term that implies no judgment of it.

Paragraph 4

She calls it a charm, a term with positive connotations.

Paragraph 5

At first he seems not sure how to interpret it. It is the “slightest possible defect,” which may actually be part of her beauty, but then he quickly reveals what he really thinks: it is “the visible mark of earthly imperfection.”

Paragraph 7

The language associates the birthmark first with attractiveness (it lured lovers), then with desire and intimacy (those lovers wanted to “press their lips” to it).

19. How do women interpret the birthmark and why?

They see it a blemish that destroys Georgiana’s beauty. The narrator suggests they are motivated by jealousy. In an ironic way their claim that the mark destroys her attractiveness actually testifies to how beautiful she actually is.

20. What does the birthmark’s resemblance to a hand suggest?

Its hand-like shape suggests its grip on Georgiana. It is “holding” Georgiana in two ways: it’s holding her down, which is to say that it is linking her to life on earth, and it’s holding her back, which is to say that it stands between her and perfection.

21. In what sentence does the narrator state his view of the birthmark? How does he interpret it?

He states his view in sentence 10. He sees it as a minor flaw that does not distract from Georgiana’s beauty.

22. In sentence 11 the narrator tells us how some men interpreted the birthmark and suggests that Aylmer saw it the same way for a while. How would you characterize their interpretation? What language separates this view from Aylmer’s later response to the birthmark?

These men took what might be called a reasonable view of it. To them it was a mere blemish; they “contented” themselves with simply “wishing” it would go away. They did not come to obsess over it, as Aylmer eventually did.

23. What, according to the narrator, determines how people will interpret the birthmark?

“Differences of temperament”

24. What does this suggest about Aylmer’s interpretation of the birthmark?

That it is really a construction of his own temperament.

Paragraph 8

Georgiana’s emotional life but beyond that the very the throbbing of her heart. Here the birthmark comes to symbolize her life.

26. In what way can this last meaning be said to be a foreshadowing?

If the birthmark symbolizes Georgiana’s very life, then when she loses it, she ceases to live.

27. What meaning does Aylmer finally assign to the birthmark?

For him it becomes the symbol of Georgiana’s flawed humanity.

28. What does the narrator’s use of the verb “select” suggest?

It suggests that Aylmer had a choice in deciding upon the meaning of the birthmark. The narrator has given us a variety of meanings he could have selected, but he chose to see it as a “symbol of… sin, sorrow, decay, and death.”

29. According to the narrator, what is the origin of this meaning?

Aylmer’s “somber imagination.” This echoes the narrator’s remark in paragraph 7 that “differences in temperament” account for differences in interpretation.

30. Thus far we have reached three important interpretative conclusions.

- We established that Aylmer is a spiritual striver; he seeks greater refinement and spirituality in his life.

- We established that he sees Georgiana as his link to this more spiritual existence.

- We have established that he sees the birthmark as a defect that stands between her and the higher spirituality of perfection.

How do these interpretative conclusions help explain Aylmer’s obsession to remove the birthmark?

If Aylmer hopes to connect with a higher level of spirituality through his marriage to Georgiana, then the birthmark, by holding Georgiana back from the highest level, also inhibits his spiritual growth. That it stands as an obstacle to his own spiritual aspirations helps to explain his eagerness to remove it.

Aylmer as Scientist: Paragraph 22

When he was a young man, “during his toilsome youth.”

32. What effect did those discoveries have on his career?

They won him fame, “the admiration of all the learned societies in Europe.”

33. How does the work we see Aylmer doing as an old man in the story reflect the work he did when young?

Volcanoes — which produce heat, soot, and gas — are similar to the furnace over which he toils in his laboratory, and his interest in geysers displays an alchemist’s interest in transforming the elements of the earth’s “dark bosom” into things bright, pure, and virtuous (see background note). This latter interest, which he held even as young man, suggests the extent to which Aylmer has long desired to refine, purify, and, in effect, spiritualize, the base elements of nature. In the story he has redirected this purifying impulse away from rocks, minerals, and water to flesh, blood, and bone.

34. Why might it be said that fathoming the “process by which Nature… create[s] man, her masterpiece” represents the ultimate in scientific discovery?

The process of creation “assimilates all” of nature’s influences “from earth… air… and the spirit world.” To understand how nature does that would be to master all those realms.

35. What field of study confronts Aylmer with his greatest professional setback?

The study of the human body. Through it he discovers the limits of his ability to understand nature.

Paragraph 51

The narrator notes “his eager aspiration toward the infinite,” an aspiration which he is pursuing in his treatment of Georgiana.

37. How does Georgiana come to judge Aylmer’s career?

She sees it as a failure.

38. What language indicates that Aylmer shared this judgment?

“His brightest diamonds were the merest pebbles, and felt to be so by himself.”

39. What is the difference between the way other scientists see Aylmer and the way he sees himself?

The scientific community sees him as a renowned expert — an “eminent,” to quote the story’s first sentence. Yet he sees himself as a failure. There is a gap between his public image and private sense of himself.

40. What does the term “composite man” mean?

It describes the narrator’s view of human nature; humans are made of body (clay) and soul (spirit).

41. How does sentence 8 describe Aylmer’s situation?

He works “in matter” and is “burdened with clay.” He seeks to realize his “higher nature” but is “thwarted” by his “earthly part.”

Paragraph 55

It represents his ultimate triumph, the one that will make him genuinely worthy of worship, thereby closing the gap between his public image of success and his private sense of failure.

43. With your analysis of Aylmer’s achievements as a scientist in mind, speculate on why the narrator in paragraph 1, sentence 5 asserts that he does not know if Aylmer believed science can control nature.

The narrator cannot assume that Aylmer believes in science’s ability to control nature because he knows that there is little in Aylmer’s experience to suggest it can. Aylmer has spent a career trying to understand and control nature, yet he judges that career a failure. He came to understand the limits of science when, studying the human body, he realized how thoroughly nature defends its secrets from even the most learned inquiry.

Outline a brief paper. Practice structuring an argument, identifying textual evidence, and articulating connections between elements of an argument.

Follow Up Assignment

Based on the outline developed in the interactive exercise, write a paper on Aylmer’s motives in “The Birthmark.” You may want to have students print out slide 5 of the exercise to serve as a guide.

Vocabulary Pop-Ups

- eminent: distinguished, high rank

- countenance: face

- ardent: enthusiastic

- votaries: dedicated follower

- swain: a lover or suitor

- fastidious: attentive to detail, meticulous

- ineffaceably: can’t be erased

- somber: gloomy and dark

- apprised: informed, told

- repose: rest

- melancholy: depressed and gloomy state of mind

Images:

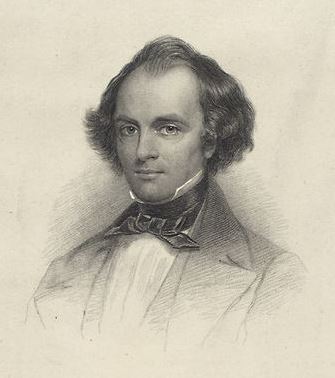

Portrait of Nathaniel Hawthorne, steel engraving by Thomas Phillibrown, 1851, after the 1850 oil portrait by Cephas G. Thompson. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Digital ID 483529.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, TEACHER RESOURCES : E-NEWSLETTER : COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY. Originally appeared in the Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter (Winter 1997) and was written by Elizabeth Maurer. http://www.history.org/history/teaching/enewsletter/volume7/mar09/courtship.cfm. Accessed August 18, 2014