CONSTITUTION: 1787-1791

6. Inaugurating a Government

- On establishing the first government under the Constitution: commentary, 1788-1795 PDF

- On the inauguration of George Washington, 30 April 1789: selections from David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, 1789 PDF

David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution,

1789, conclusion

With this appeal, David Ramsay concluded his two-volume history of the American Revolution, a work we have consulted throughout this primary source collection. A South Carolina physician, war veteran, Federalist statesman, and self-trained historian, Ramsay published the first extensive analysis of the revolutionary period, one still respected for its insight and impartiality.1 "It is now your turn," he challenged Americans, "to figure on the face of the earth. . . . Perfect the good work you have begun." That challenge was front and center for the men sworn into office as the first President, Senators, Representatives, and Justices under the Constitution. Here we examine their responses to the challenge as they inaugurated a new government.

On establishing the first government under the Constitution: commentary, 1788-1795. After years of struggling under a weak wartime government, and months of debating and voting on a new plan of government, the time arrived in spring 1789 when the new federal government was to become reality. Arriving one by one in New York City, the men elected to office brought a deep commitment to success—and the sobering knowledge that failure was not an option. Unlike revolutionary governments after them, these men did not have America's example to look back on; they had to create it. This is chapter one of a heady period—later entitled "the early republic" when the nation's future under the Constitution seemed assured. Here we read commentary from letters, news reports, and statements to Congress from late 1788 to mid 1790 that encapsulate the challenge and promise of this critical transition. (10 pp.)

On the inauguration of George Washington, 30 April 1789: selections from David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, 1789. On April 30, 1789, the first President of the United States under the new Constitution was inaugurated in New York City, the temporary capital of the nation. General George Washington—the revered Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, the president of the Constitution Convention, and the briefly retired Virginia planter—became President George Washington, the first Chief Executive of the new federal government. The exaltation and grandeur of this event was captured by David Ramsay in the final chapter of his history of the American Revolution, in which he included Washington's Inaugural Address and descriptions of his triumphal journey from Mount Vernon to New York City. (7 pp.)

Discussion Questions

- What were the most significant challenges for the new president, senators, and representatives in 1789 and 1790? Why?

- What were the most significant accomplishments of these officeholders in 1789 and 1790? Why?

- What specific issues did the first Congress address in its first months?

- What specific duties did President Washington complete in his first months in office?

- How did the media cover the activities of the President and first Congress under the Constitution? What did they find important to report?

- Why did the judicial branch have a later startup than the executive and legislative branches?

- How would you describe the public response to Washington's journey from his home in Mount Vernon, Virginia, to New York City for his inauguration? How would you describe Washington's response to the public response?

- According to Ramsay, what qualities of character made Washington an appropriate president of the new republic?

- In what ways was Washington's inauguration important as a symbolic event for all Americans? for his fellow office holders?

- How did his first inauguration ceremony and address differ from those in later centuries? What explains the changes? (See Supplemental Sites.)

- Follow the commentary of George Washington and/or James Madison throughout this Theme (in sections 1, 2, 5, and this section).

- – What did each man identify as the major obstacles and threats to the success of the new nation after 1780? to the success of the new federal government in 1789 and 1790?

- – What did each man recommend for surmounting the obstacles and threats?

- – Where did each man place his ultimate hope for the nation's success?

- Trace George Washington's concerns about the nation's future from the end of the Revolutionary War through his two presidential terms (a sampling from this primary source collection below). At his death in 1799, what most encouraged and concerned him about America's future?

- – ". . . according to the system of Policy [government] the States shall adopt at this moment, they will stand or fall, and by their confirmation or lapse it is yet to be decided whether the Revolution must ultimately be considered as a blessing or a curse—a blessing or a curse not to the present age alone, for with our fate will the destiny of unborn Millions be involved."8 June 1783

- – "Let us look to our National character and to things beyond the present period. No Morn ever dawned more favorable than ours did—and no day was ever more clouded than the present! Wisdom & good examples are necessary at this time to rescue the political machine from the impending storm. . . ."5 Nov. 1786

- – "I am truly pleased to learn that those who have been considered as [the Constitution's] most violent opposers will not only acquiesce peaceably but cooperate in its organization and content themselves with asking amendments in the manner prescribed by the Constitution. The great danger, in my view, was that everything might have been thrown into the last stage of Confusion before any government whatsoever could have been established, and that we should have suffered a political shipwreck without the aid of one friendly star to guide us into Port."16 Aug. 1788

- – "I will content myself with only saying that the elections have been hitherto vastly more favorable than we could have expected, that federal sentiments seem to be growing with uncommon rapidity, and that this increasing unanimity is not less indicative of the good disposition than the good sense of the Americans. . . . From these and some other circumstances, I really entertain greater hopes that America will not finally disappoint the expectations of her Friends than I have at almost any former period."29 Jan. 1789

- – ". . . according to the system of Policy [government] the States shall adopt at this moment, they will stand or fall, and by their confirmation or lapse it is yet to be decided whether the Revolution must ultimately be considered as a blessing or a curse—a blessing or a curse not to the present age alone, for with our fate will the destiny of unborn Millions be involved."

- Trace the commentary of Benjamin Franklin through this primary source collection (see the chronological and thematic All-Texts Lists) and in Becoming American: The British Atlantic Colonies, 1690-1763. What factors dominated Franklin's views on the colonies' rebellion and the young nation's precarious beginnings? How secure do you think he felt about the nation's future when he died in 1790?

- In your judgment, how precarious was the new nation under the new government in 1789? What factors most jeopardized its future? Which factors most assured its success?

- Compare the governments established by the United States and France after their revolutions of the late 1700s. How were their ideological bases most similar? How did the governments' creation and structure most differ? (Note the 1791 commentary by Brissot de Warville in Theme IV: INDEPENDENCE.)

- How did David Ramsay, in the conclusion to his history of the American Revolution, portray the new republic as exceptional?

- Compose a letter to David Ramsay, or a dialogue between him and you, in which you respond to his concluding words of encouragement to "perfect the good work you have begun." (See above).

Framing Questions

- How did Americans' concept of self-governance change from 1776 to 1789? Why?

- How did their emerging national identity affect this process?

- What divisions of political ideology coalesced in this process?

- How did the process lead to the final Constitution and Bill of Rights?

- How do the Constitution and the Bill of Rights reflect the ideals of the American Revolution?

Printing

On establishing the first government under the ConstitutionOn the first inauguration of George Washington, 1789

TOTAL

10 pp.

7 pp.

17 pp.

Supplemental Sites

The First Federal Congress, 1789-1791 (First Federal Congress Project, George Washington University)

Franklin's petition to Congress for the abolition of slavery, 1789 (National Archives)

On the First Inauguration of George Washington, 30 April 1789

- – Library of Congress (presidential inaugurations)

- – Library of Congress (Today in History)

- – National Archives

- – U.S. Senate

- – Architect of the Capitol

- – National Park Service (Federal Hall)

Lesson Plans (EDSITEment, NEH) George Washington's Mount Vernon Estate & Gardens (Mount Vernon Ladies' Assn.)

- – Meet George Washington

- – Essays and lectures by Mount Vernon staff, including essays on George Washington and slavery

David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, 1789, full text (Online Library of Liberty)

"Was the American Revolution Inevitable?," not-to-miss teachable essay by Prof. Francis D. Cogliano, University of Edinburgh (BBC)

Teaching the Revolution, valuable overview essay by Prof. Carol Berkin, Baruch College (CUNY)

General Online Resources

1In 1960, historian Page Smith asserted that Ramsay's history remained "the best interpretation of the causes of the Revolution. . . . In his analysis and interpretation of the events culminating in the Revolution, he showed unusual insight and a keen sense of proportion." Page Smith, "David Ramsay and the Causes of the American Revolution," The William and Mary Quarterly, 3d. Series, 17:1 (January 1960), pp. 51-77.

Images:

– Federal Hall, The Seat of Congress, depicting the inauguration of George Washington, 30 April 1789, Federal Hall, New York City; 1790 drawing by Peter Lacour and engraving by Amos Doolittle; 2000 photograph of engraving in the private collection of Louis Alan Talley, Washington, DC (detail). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC4-7831 DLC.

– George Washington, oil portrait by Gilbert Stuart (the Lansdowne Portrait), 1796. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Bequest of William Bingham, 1811.2; reproduced by permission.

– A Display of the United States of America, engraving by Amos Doolittle, Connecticut, 1794 (detail). Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, Gift of Mrs. George L. Andrew, 1910, SC-4; permission pending.

– John Adams, portrait by John Singleton Copley, oil on canvas, 1783 (detail). Harvard University Portrait Collection, Bequest of Ward Nicholas Boylston to Harvard College, 1828, H74; reproduced by permission.

– "The New Congress," poem, The Massachusetts Centinel (Boston), 4 March 1789, p. 196. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, accessed through America's Historical Newspapers, American Antiquarian Society with Readex/NewsBank.

– "From our Correspondent," The New Hampshire Gazette, and General Advertiser (Portsmouth, NH), 1 April 1789, p. 3 (detail). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, accessed through America's Historical Newspapers, American Antiquarian Society with Readex/NewsBank.

– John Jay, portrait in judicial robes by Gilbert Stuart, oil on canvas, 1794. National Gallery of Art, Gift of the Jay Family, 2009.132.1; permission request submitted.

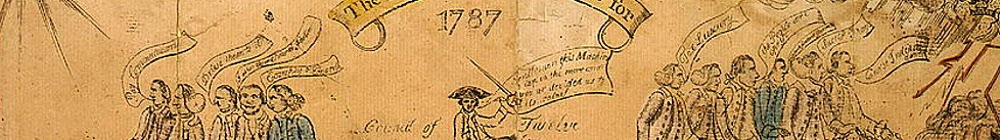

Banner image: Amos Doolittle, The Looking Glass for 1787, engraving, cartoon on the Connecticut ratification debates, 1787 (detail). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC4-1722.

*PDF file - You will need software on your computer that allows you to read and print Portable Document Format (PDF) files, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you do not have this software, you may download it FREE from Adobe's Web site.