CONSTITUTION: 1787-1791

2. Creating a New Constitution

- On creating the U.S. Constitution: commentary by delegates and observers, 1787 PDF

- The United States Constitution, 1787 National Archives – print version

Edmund S. Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763-89 (1956)

When we study the Constitutional Convention of 1787, we know its ultimate outcome—a new plan of government that was ratified, implemented, and amended twenty-seven times; that is honored as a model for democratic self-government and is perpetually examined for its meaning in changing times. But in May 1787, the fifty-five men who convened in Philadelphia to save the fledgling nation had no guarantee of success. "Most of them were convinced," continues historian Edmund Morgan, "that unless they came up with an acceptable, and at the same time workable, scheme of national government the union would dissolve."1 A fearsome prospect. As you study the delegates' deliberations—the Virginia Plan vs. the New York Plan, the Great Compromise, the three-fifths compromise—and their final plan of government, consider the "urgency of the task" that propelled them through the summer of 1787.

On creating the U.S. Constitution: commentary by delegates and observers, 1787. After meeting on ninety-seven days from May 25 to September 17, 1787, the convention submitted a new plan of government to the states for their approval or rejection. It had been an arduous and contentious process, sustained through debate and compromise—and the realization that failure to revise or replace the moribund Articles of Confederation could doom the new nation to "anarchy and confusion," as George Washington feared. Because the delegates agreed to keep their deliberations secret, little was known of their progress and setbacks until after the convention adjourned. Collected here are statements from nine delegates and nine non-delegates that reveal the anxious yet exhilarating summer of 1787, and the first months of the ratification debates. What new perspective on the Constitutional Convention and its final document do you gain from reading the commentary? What do you learn about the Founding Fathers? Which man would you most want to ask for amplication on his views and sentiments? (9 pp.)

The United States Constitution, 1787. Five articles and 4,543 words, with some of the most familiar phrases in American history—We the People, a more perfect Union, the Blessings of Liberty, Advice and Consent, Full Faith and Credit, and supreme law of the Land. Other phrases remind us that the document is over two hundred years old, such as Corruption of Blood, Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and the finally struck three fifths of all other persons. It takes about half an hour to read the U.S. Constitution, and perhaps an hour to study a well-annotated text. What new perspective on the Constitution do you gain after reading the views of the convention delegates and other citizens in 1787? See Supplemental Sites below for other online annotated texts of the Constitution; the commentary provided on the U.S. Senate Virtual Reference Desk is especially useful but prints out to twenty-plus pages. (8 pp., printer-friendly version from the National Archives.)

Discussion Questions

- What new perspective on the Constitutional Convention and its final document did you gain from the 1787 commentary? Did anything surprise you?

- What did you learn about the Founding Fathers?

- What anxiety did Washington express in the first letter of the commentary (May 1787)? How did he describe the convention in the last letter (November 1787)?

- How did other delegates express their trepidation about the vital task set before them?

- What encouraged the delegates about their assembly and its prospects?

- Give arguments for and against the delegates' maintaining secrecy during the convention. How did it help or impede their progress? How did it influence the public's view of their deliberations?

- What rumors were spread while the delegates conducted their secret deliberations? What do they reveal about the nation's fears and hopes at the time?

- Why did George Mason feel that revolting from Great Britain was "nothing compared" to creating a new plan of government?

- Why did Federalists fear anarchy and dissolution of the union if the Constitution were not adopted?

- Why did Anti-Federalist fear civil war if the Constitution were adopted?

- Explain the two questions that Washington recommended to challenge opponents of the Constitution.

- What differentiates the commentary of the Federalists and Anti-Federalists in this collection? (The Anti-Federalists in the collection are delegates George Mason and Elbridge Gerry, and non-delegates Richard Henry Lee and Arthur Lee.)

- Which man would you most want to ask to amplify his views and sentiments? What would you ask?

- Write an essay about the 1787 convention based on one of the statements below. Choose the point of view of a delegate, an American or European observer in 1787, or a 21st-century student.

- – The eyes of the United States are turned upon this assembly . . .

George Mason

- – Our affairs are considered on all hands as at a most serious crisis.

James Madison

- – Will they agree upon a System energetic and effectual, or will they break up without doing anything to the Purpose?

William Paterson

- – They might by perseverance establish a Government calculated . . . to make the Revolution a blessing instead of a curse.

David Humphreys

- – If the present moment be lost, it is hard to say what may be our fate . . . .

James Madison

- – Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best . . .

Benjamin Franklin

- – Democracy has never before appeared under a similar form, & has never been so balanced.

Jean de Crèvecoeur

- – If [the constitution] should be established, either a tyranny will result from it or it will be prevented by a civil war.

Richard Henry Lee

- – "Well, Doctor [Franklin], what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?"

"A republic, if you can keep it."James McHenry

- – The eyes of the United States are turned upon this assembly . . .

- What new perspective on the Constitution itself as an American founding document did you gain after reading the 1787 commentary?

Framing Questions

- How did Americans' concept of self-governance change from 1776 to 1789? Why?

- How did their emerging national identity affect this process?

- What divisions of political ideology coalesced in this process?

- How did the process lead to the final Constitution and Bill of Rights?

- How do the Constitution and the Bill of Rights reflect the ideals of the American Revolution?

Printing

Commentary on creating the U.S. ConstitutionThe U.S. Constitution (without amendments)

TOTAL

9 pp.

8 pp.

17 pp.

Supplemental Sites

- – text & amendments, with annotations (U.S. Senate)

- – text with commentary, without amendments (U.S. State Department)

- – text with advanced commentary, with amendments (Cornell University Law School)

- – text with advanced commentary, with amendments (National Constitution Center)

- – text with amended and superceded items hyperlinked, without amendments (National Archives)

The Constitutional Convention of 1787, overview by Prof. A. E. Dick Howard (U.S. State Department)

The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, Max Farrand, 1911 (Library of Congress)

Selected Correspondence from the Summer of 1787 (Ashbrook Center for Public Affairs, Ashland University)

To Form A More Perfect Union (Library of Congress)

America's Founding Fathers: Delegates to the Constitutional Convention (National Archives)

The Constitution, History Now, Sept. 2007 (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

- – George Washington and the Constitution, by Theodore J. Crackel

- – James Madison and the Constitution, by Jack Rakove

- – Race and the American Constitution, by James O. Horton

Elbridge Gerry, letter to the Massachusetts Legislature on his objections to the Constitution, Nov. 1787 (Ashbrook Center for Public Affairs)

George Mason, Objections to this Constitution of Government, 16 Sept. 1787 (Gunston Hall)

"Was the American Revolution Inevitable?," not-to-miss teachable essay by Prof. Francis D. Cogliano, University of Edinburgh (BBC)

Teaching the Revolution, valuable overview essay by Prof. Carol Berkin, Baruch College (CUNY)

General Online Resources

1 Edmund S. Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763-89 (The University of Chicago Press, 1956, 3d. ed., 1992), p. 134.

Images: The United States Constitution, adopted and signed 17 September 1787, pp. 1, 4 (details). Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives.

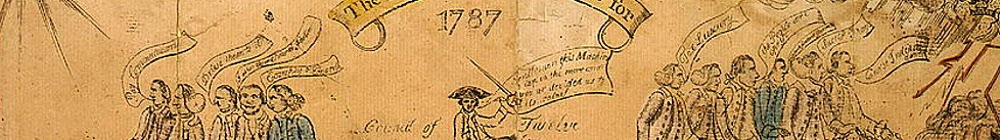

Banner image: Amos Doolittle, The Looking Glass for 1787, engraving, cartoon on the Connecticut ratification debates, 1787 (detail). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC4-1722.

*PDF file - You will need software on your computer that allows you to read and print Portable Document Format (PDF) files, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you do not have this software, you may download it FREE from Adobe's Web site.